About a decade ago, my company, The Delahaye Group, noticed an interesting trend. Corporate crises where the company involved did not swiftly deal with a problem lasted a lot longer than crises in which the organization quickly addressed the issues. We illustrated this in a series of graphs that analyzed, simply, the volume of coverage–we didn’t even bother figuring out what was positive or negative.

In 1995, Intel, for months, famously denied the existence of a flaw in its Pentium chip. The media kept the story alive with a steady stream of customer complaints. Finally, months later, Intel recalled the chip.

Similarly, in 1998, Columbia HCA denied for months that it was under investigation, despite reports that federal agents had searched its offices. The negative press went on for more than a year.

In contrast, in 1996, beverage company Odwalla found contaminated juice in one of its shipments. Immediately it issued an apology and was famously transparent about the crisis. The negative press dissipated within weeks, even though a child died from contaminated juice.

Several decades later, Fullintel research, overseen by myself and crisis guru W. Timothy Coombs of Texas A&M, proved the same thing. Fullintel analyzed decades of media coverage using its AI algorithm. It found companies that say no comment or blame a scapegoat or the victim and/or flat-out deny a crisis are likely to prolong it. Companies that provide information or offer an apology promptly help put a crisis to bed.

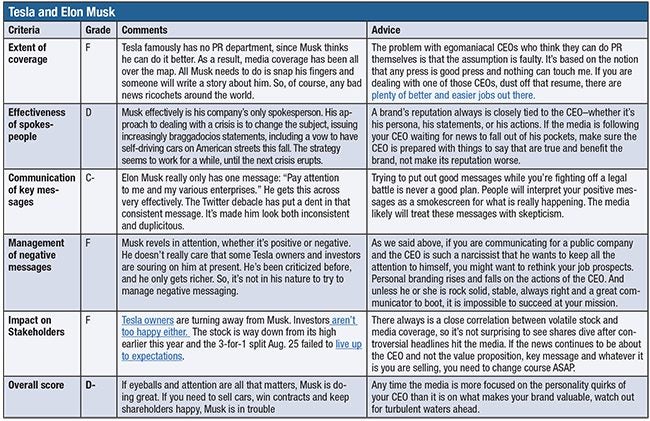

We see the advantages of promptly addressing issues all the time now. Fast response is part of most organizations’ crisis bible. And yet, some people and their companies just don’t learn. Most often, the cause is the CEO’s ego. The poster child is Elon Musk. His erratic behavior and outrageous and frequently out-of-touch statements are seen as just part of his brand. But the once-valuable brand is beginning to show signs of strain.

Just as often it is the ego/culture of a company that just can’t seem to come clean no matter what. Here, the poster child is Ericsson, the Swedish telecom.

Tesla and Elon Musk

Elon Musk has gone from media darling to media punching bag. In part this is due to the debacle that was his announced desire to purchase Twitter for $44 billion, which became official April 14. Since then it’s been a prolonged back-and-forth as he’s tried to shake free of his offer. He’s sold some $15 billion worth of Tesla shares in April and August just in case a Delaware judge rules he must stick to his word and purchase Twitter. The case is scheduled for Oct. 17, though Musk is seeking a delay.

Actually, Musk was beginning to lose his luster before he started his on-again/off-again dance with Twitter. Problems with the left began when he started bashing President Joe Biden’s policies, apparently in a fit of pique over being excluded from some of the White House’s electric car conversations.

In addition, his proposed purchase of Twitter gave journalists the heebie jeebies. Since most of the media lives on Twitter and relies on it for news tips, a collective gasp went up in newsrooms worldwide at the notion that Musk might one day own the platform. As a result, his media image took a dive reminiscent of a SpaceX satellite in a solar storm.

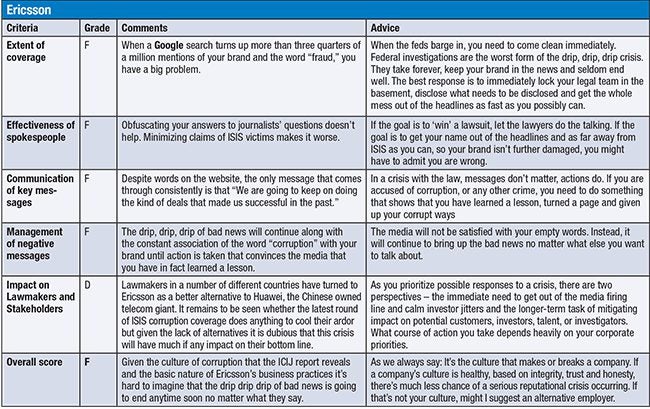

Ericsson

If you’re a PR pro and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) does a detailed report about your company, you just know it’s going to be a very bad year. That was the case at Ericsson, the Swedish Telecom giant. It was accused of doing business with Islamic State and ISIS. Moreover, it was accused of corrupt practices in more than a dozen other countries.

The ICIJ story, which was published in February, covers activities from 2011 to 2019. It was based on a leaked internal report.

Previously, Ericsson settled bribery charges from the U.S. Department of Justice as well as the U.S. Security and Exchange Commission, in 2013. So, it wasn't unaware of issues when the ICIJ report appeared.

When the ICIJ informed Ericsson of the story, the company issued a public statement (Feb. 15, 2022). It acknowledged “corruption-related misconduct” in Iraq and payments to ISIS.

In addition, Ericsson CEO Börje Ekholm granted interviews to news outlets not in possession of the leaked report. “We can’t determine where money sometimes really goes, but we can see that it has disappeared,” Ekholm told a Swedish newspaper. Not what most would call a transparent response, despite the anti-corruption commitments on its website.

Last month, victims of ISIS and al Qaeda sued Ericsson, seeking restitution for harm done to their loved ones. Ericsson said it would “zealously defend against” the suit.