Company: United Airlines

Timeframe: March 2008-present

In March 2008, Canadian band Sons Of Maxwell was on tour when one of its members, Dave Carroll, witnessed United Airlines baggage handlers tossing his guitar around recklessly. The instrument ended up being severely damaged as a result, and Carroll spent the next nine months working through United’s customer service system to get reparations—to no avail.

After his failed attempt to get a reasonable acknowledgement of the customer service faux pas from the airline, Carroll took a different approach—writing a song and recording a video entitled, “United Breaks Guitars,” which includes the lyrics:

“Well, I won’t say that I’ll never fly with you again,

’Cause, maybe, to save the world, I probably would,

But that won’t likely happen,

And if it did, I wouldn’t bring my luggage

’Cause you’d just go and break it,

Into a thousand pieces,

Just like you broke my heart.”

On July 6, 2009, Carroll posted the video on YouTube; a week later, it had picked up 2.5 million views, generated more than 800 blog posts and almost 14,000 comments and prompted an untold number of Twitter messages. Amid all the attention being paid to social media, Carroll’s online fame drove mainstream media to cover his plight.

Upon learning of the song, United representatives immediately offered to pay for his guitar, but Carroll was already a lost cause. He said he’d be happy to allow them to donate a comparable amount of money to a charity of their choice, but, as for his own promotion of the song, he had no intention of stopping. The company gave $3,000 to the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, but the damage to the United brand had already been done.

|

| When United Airlines failed to address musician Dave Carroll’s complaint that baggage handlers destroyed his guitar, he took matters into his own hands, creating a song and music video entitled “United Breaks Guitars.” |

A STAR IS BORN

By any measure, Carroll’s damaged guitar has brought him far more publicity than playing the guitar itself could have, despite his award-winning career. As of July 13, 2009, his songwriting abilities had been exposed to more than 2 million new fans; his band’s Web site had received a significant surge in traffic; and he had garnered media coverage that even a big budget couldn’t buy, including prime-time exposure on CBS ’ Early Show.

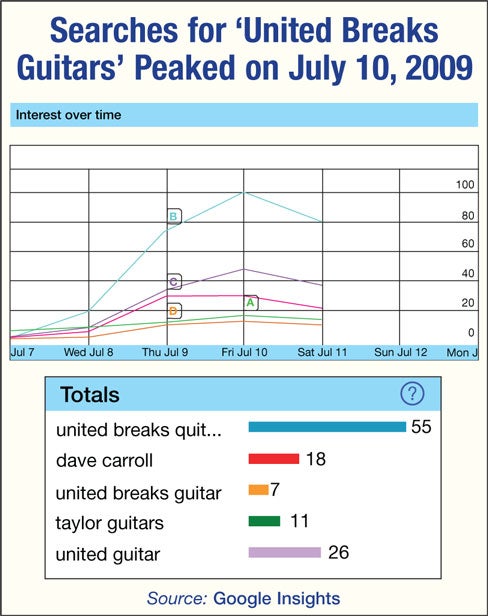

Plus, over a short period of time, a huge spike in users entered the search term “United Breaks Guitars” into Google; graphs from Google Insights tell a compelling story (see below), in which search queries for the video peaked on July 10.

Certainly Carroll’s success story is unique to his experience, but the broader situation—having a crisis spread rapidly via an online platform—is more the rule than the exception, thanks to the proliferation of social media. Then there are Web sites like Consumerist.com, which chronicle the trials and tribulations consumers go through trying to get satisfaction from the corporations they do business with.

Now-defunct Circuit City felt the wrath of Consumerist.com when an e-mail from a store manager ended up in editor Ben Popken’s inbox. The e-mail, sent from an operations employee to all store managers, demanded that all issues of MAD magazine available at each retail outlet be removed because they included a good-natured parody called “Sucker City.”

When the Consumerist.com’s editor caught wind of the e-mail, he posted it on the site, which is how the Circuit City’s VP of communications, Jim Babb, became aware of the situation. Luckily, Babb’s graceful response to Popken, which came in the form of a humorous e-mail, mitigated the crisis.

“Beyond the obvious ‘this cannot be ignored’ element, the situation frankly called out for immediate action to correct the original mistake,” Babb said in an interview that appeared in the PR News article, “How Circuit City’s PR Team Recovered From A Self-Inflicted Wound” (Aug. 19, 2008). “We responded quickly because it was the right thing to do and because it made sense from a PR point of view.”

Pro-customer sites like Consumerist.com also post the e-mail addresses and phone numbers of senior executives at companies including US Airways and Capitol One in order to make it easier for consumers to solve their problems, in turn making the Kabuki that aggrieved consumers and corporate PR people go through all too familiar. In brief:

1. Company does bad thing and refuses to back down when challenged.

2. Consumer blogs/tweets/complains on Facebook and gets online and sometimes mainstream media attention.

3. Company tweaks policy, apologizes and makes meaningful restitution.

4. Everybody is happy.

What’s new here, though, is that Carroll appears to understand the incredibly valuable publicity this situation has brought him. Usually, an angry consumer loses public support when they refuse to accept restitution from the company that wronged them. Media consumers are fascinated by angry underdog stories, but have no patience for unreasonable people to whom restitution has been offered.

Dave Carroll is a different breed, though. For starters, he’s got a sense of humor and is a genuine musical talent. In short, he has all the tools he needs to stretch his quick hit of fame into a longer story.

As for United, it’s no help in retrospect, but it would have been better if the company’s baggage handlers had destroyed a less-talented musician’s guitar.

RESTITUTIONS SANS APOLOGIES = A SURE-TO-FAIL CRISIS PLAN

United Airlines is in a pickle. They can’t make Dave Carroll stop singing, or make him any less sympathetic without demonizing him, which would backfire. The standard response in this situation was previously coined by Consumerist.com’s Popken as “the three-step system for fixing corporate gaffes” (see sidebar for the three-step system in the context of United’s current crisis):

1. Admit you were wrong.

2. Stop doing the wrong thing.

3. Make a material gesture of apology.

Though it won’t stop Carroll from releasing two more similarly themed videos as planned, United should write an apology and address the procedural errors that resulted in Carroll’s nine-month runaround. The lack of a clear, well-publicized apology still stands out as a missing piece of the brand’s response. Ultimately, this will blow over—unless United’s baggage handlers damage the luggage of another talented person. PRN

CONTACT:

This article was written by Shabbir J. Imber Safdar, founder of Virilion Inc., and David L. Haase, director of Virilion’s Editorial Services Department. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].