When the “Kony 2012” video hit the Internet on March 5, 2012, it’s safe to say that the majority of the public had no clue about the organization behind it, Invisible Children. But six days and 100+ million views later, the public became very interested in Invisible Children, as criticism of the 30-minute film’s content and questions about the group’s financial model cropped up on Facebook, Twitter and in the mainstream media.

Invisible Children didn’t take long to respond to its critics—in a matter of hours it posted a video that featured CEO Ben Keesey deliberately and calmly answering every criticism. A written response was also posted on the group’s Web site. It was clear that Invisible Children had handled the situation in Crisis 101 textbook fashion, quickly responding to the issues raised in a transparent manner.

But is speed overrated in a crisis? And is there ever a time when it’s best to slow down, even when your brand is taking a monumental viral hit online? Opinions vary.

According to Priya Ramesh, director of social media at CRT/tanaka, speed is of the essence, particularly online. “You have to demonstrate to your audience that you’re listening. ‘We heard you, and we’re working on it’ is what is required at the start,” she says.

Ramesh thinks back to two different crises when considering the speed factor. In Oct. 2011, BlackBerry-maker RIM experienced massive service outages across the globe. The company’s response was tepid via social media, says Ramesh. “It took them four days to respond via Twitter and blog posts,” she says.

In contrast, in July 2009 Network Solutions (a CRT/tanaka client) discovered that information on 500,000 credit cards in its database had been compromised. “We had been through several rehearsals if something like that were to happen,” says Ramesh. A pre-built dark microsite was quickly fired up, and within a few hours round-the-clock updates were being given to customers.

SPEED OVERRATED?

That’s the conventional wisdom: Don’t let panic about your brand spread across channels. But crisis consultant Eric Dezenhall of Dezenhall Resources doesn’t entirely agree with that strategy. “The whole concept of responding quickly is a cliché because it implies that responding quickly is always the answer. It isn’t,” says Dezenhall. “I’ve had cases where responding quickly has helped neutralize unwarranted attacks and cases where we made the call to not respond quickly on the grounds that it would inflame a non-story.”

PR people, says Dezenhall, love the whole “respond quickly bromide” because it’s how they make their living—executing tactics. The truth is that it’s a judgment call, and depends on the answer to a few questions:

1. Is the information being trafficked false and defamatory or just something you don’t like?

2. Does the issue have the potential to catch on?

3. How might your critics respond to your response?

|

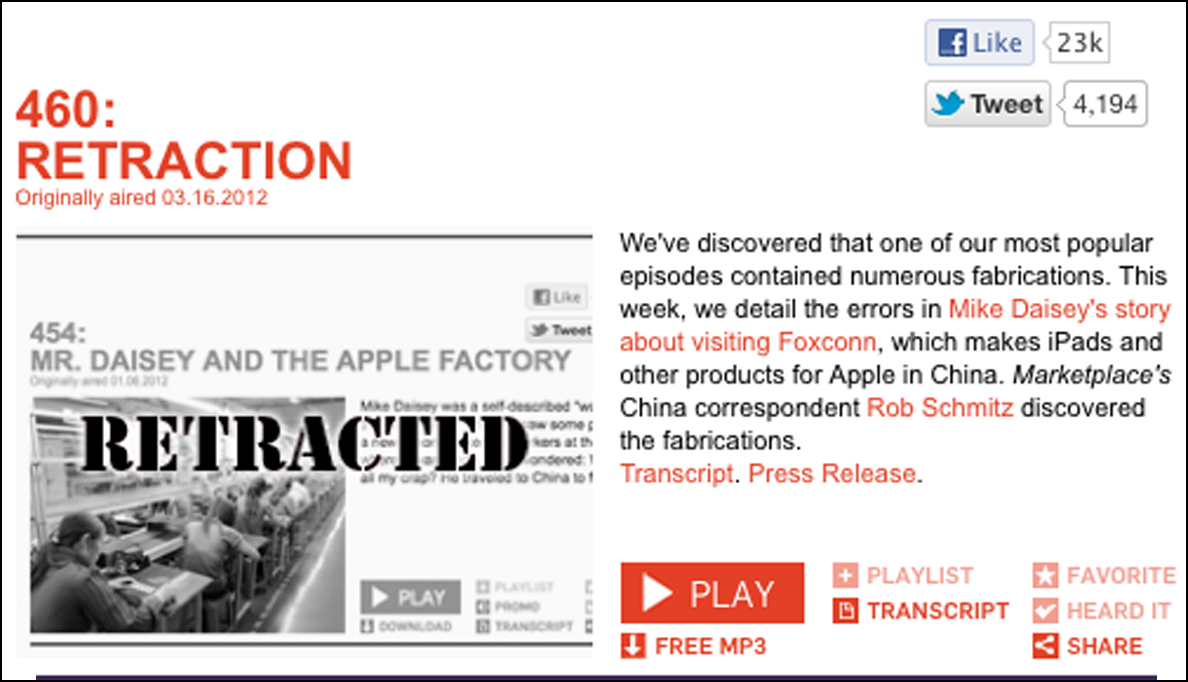

| Within 24 hours of airing a program that featured fabricated information about the tech plant Foxconn in China, NPR’s This American Life posted a retraction on its site. |

THIS AMERICAN CRISIS

Surely Dezenhall wouldn’t have a beef with the response of NPR’s This American Life after it was revealed that actor Mike Daisey had fabricated much of his account of conditions at Apple supplier’s Foxconn’s plant in southern China. A shortened version of Daisey’s The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs theater piece had been presented Jan. 6, 2012, on the radio show, becoming its most downloaded presentation. But after Daisey admitted to inaccuracies in its content, This American Life responded the next day with an audio retraction of its original broadcast, including an interview with Daisey in which the actor said he had made a “mistake that I truly regret.”

Kathy Fieweger, executive VP and GM at MWW Chicago, says pulling the trigger on an apology or retraction depends on how much the media is wrapped up in the situation.

“If they’re not, releasing a statement can be foolish—in essence fueling a fire that was only a spark. It’s the ‘first, do no harm’ credo in action,” she says.

In the case of This American Life, the media was all over the story, fueled by an in-depth investigative article about Foxconn that appeared in January in The New York Times. Couple that with the visibility of Apple, and there’s no doubt that speed was of the essence.

ATTACK MODE

Still, Dezenhall points out that all crises are different, including ones involving social media. “I had a consumer product client a few years ago that responded to critics on Facebook on their page. Reaction was swift and hostile,” he says.

It turns out the same consumers that claimed to want answers from the company just wanted to attack, and that engagement backfired.

Which demonstrates that whether you’re driving fast on the highway or responding quickly to a crisis, speed can be a dangerous proposition. PRN

[Editor’s Note: For more content on crisis communications, visit the PR News Subscriber Resource Center: prnewsonline.com/subscriber_resources.html. And catch Priya Ramesh at the PR Measurement Conference in Washington, D.C., on April 18— prnewsonline.com/conferences/measurement_conf2012.html.]

CONTACT:

Priya Ramesh, [email protected]; Eric Dezenhall, [email protected]; Kathy Fieweger, [email protected].