Veteran communicator Andy Gilman of CommCore Consulting remembers taking the Sabin polio vaccine in the 1960s. “It was a sugar cube [with the vaccine on it]. Everybody wanted to take it.” Kids liked the sugar, and adults felt getting vaccinated was patriotic. So far, the atmosphere surrounding coronavirus vaccination in the US isn’t like that.

How could it be? The definition of patriotism seems cloudy in a country with a significant political divide. In addition, the virus and steps to slow its spread have become political. Not surprisingly, there’s a correlation between a person’s politics and his/her attitude toward the vaccine.

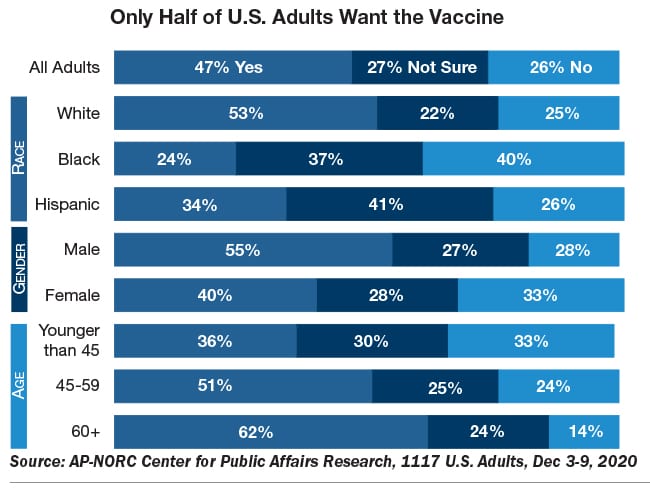

In a December 2020 Associated Press-NORC poll, 60 percent of Democrats said they’d take a vaccine; just 40 percent of Republicans said they would. Overall, about half of those surveyed say they will vaccinate (see chart, page 9).

Moreover, well before the vaccine arrived, messaging around the virus was mixed, confusing the public. Early on, the president downplayed the novel coronavirus. Later, he largely ignored the White House task force’s recommendations about masks and social distancing.

After it was apparent the virus was becoming a health, political and PR crisis, the president stopped mentioning the pandemic during public appearances. Adding to the confusion, he maintained a lively correspondence about the virus on social media, touting progress on the vaccine and attacking scientific and medical groups that published more sobering assessments, including government-run organizations, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The president’s attacks on science, the CDC and FDA added to the public’s confusion. It’s set up a trust morass that plagues the vaccination process.

A Confusing Virus

It’s not that coronavirus needed help confusing people, since it’s often masked in asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic cases. As such, it’s believed that many Americans have the virus, but aren’t displaying symptoms. Those who are pre-symptomatic, though, can transmit it.

The issue for communicators is that the virus may appear as less of a threat than it actually is. This reduces the public’s interest in cautionary messages.

Moreover, many cases are mild, with patients recovering within weeks, at home. Again, the perceived importance of virus-related messages is lowered.

It’s not a surprise, then, that getting enough people to believe coronavirus is real and requires vaccination is challenging.

With emergency approval of vaccines, the need to communicate the importance of prompt vaccination seems obvious: Without 75-80 percent of Americans vaccinated, herd immunity, leading to a return to normalcy, will not be reached. And now, with the discovery of an additional, more contagious virus strain, getting Americans vaccinated promptly seems even more critical.

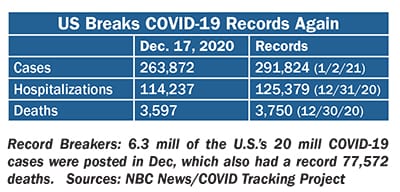

Yet, the situation remains muddy for several reasons. The lack of a solid federal roll-out plan has damaged the vaccination process, further reducing public confidence. Washington has shifted responsibility for vaccination onto the states, but they’re starved for resources. Since December was the worst month since the pandemic began, the US healthcare system is overloaded, slowing vaccination. Roughly 4 million Americans received the vaccine as of early January, though the goal for 2020 was to vaccinate 20 million. At our press time, another source of confusion were reports that doses of the Moderna vaccine might be reduced to speed up the roll out.

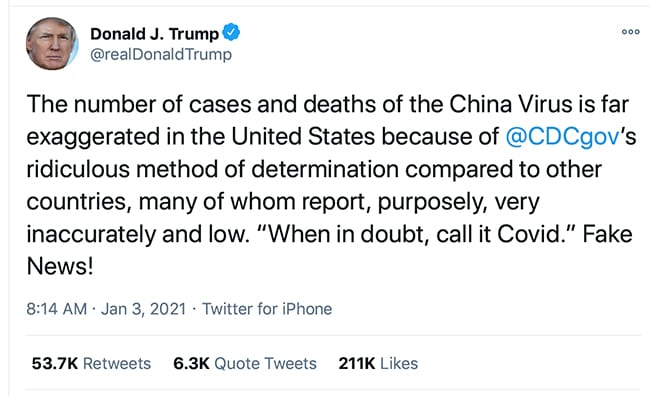

And more confusion. Just days into the new year, the president again tried to downplay the threat. On Jan. 3, he blasted reports of how many Americans have been lost since the pandemic began. The death total, he tweeted, is “far exaggerated” owing to the CDC’s “ridiculous method” of reporting. It’s “Fake news!”

And the president is not alone. Weeks earlier, incoming House member Bob Good, a Republican from VA, told a rally in DC that the pandemic is “phony.” Gathered to support the president’s attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election result, the crowd cheered.

These messages only foment what medical professionals are calling COVID disbelief. In short, it’s that people don’t believe the virus is a serious threat to them. As a result, messaging may fail.

In a survey of U.S. physicians, nearly half (48 percent) said disbelief in the virus’s being a significant threat to them will be one of the top three factors deterring their adult patients from taking the vaccine. The other two top factors were concern over vaccine safety and potential side-effects (87 percent) and doubt about the vaccine’s efficacy, making it not worth the trouble (61 percent).

Trouble might be the best word to describe the vaccination process in the U.S. so far. Slow and confusingalso are appropriate. In the period between Christmas and New Year’s, media was filled with reports about the slow pace of vaccination. Where states offered vaccines on a first-come, first-serve basis, reports of long lines, jammed web sites and busy phonelines were ubiquitous. These media reports did little to inspire public confidence in vaccination.

Healthcare Workers Are Reluctant

In many states, elderly facility patients, health workers and other frontline employees were designated as the earliest vaccine recipients. Still, there were issues.

Ohio governor Mike DeWine said early this month that 60 percent of healthcare workers in his state elected not to take the vaccine. Only about half the frontline and healthcare workers in NYC and LA were willing to get vaccinated.

The Orange County Corrections Department surveyed its 1,500-person staff late last month about interest in taking the vaccine if offered. PRNEWS requested the results. Of the 52 percent of corrections staff who responded, just 33 percent said they were interested in taking the vaccine now. Corrections staff is diverse, and the minimum education for employment is a high school diploma, an Orange County Corrections communicator tells us.

There are several reasons behind this reluctance. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey last month found they include a concern about side effects (59 percent), lack of trust in government (55 percent), worries that the vaccine is too new (53 percent), and concerns over politics’ role in the development process (51 percent).

Good News on Messaging

Fortunately, messaging to promote vaccination is in the works. For example, late last month, The Ad Council debuted an effort aimed at raising confidence in healthcare workers about the vaccine via educational videos. A partnership with the COVID Collaborative, the videos were created with several scientific groups, including the CDC, and membership associations, such as the National Association of Hispanic Nurses and the National Black Nurses Association.

In addition, The Ad Council is behind a vaccine PSA campaign aimed at the general public. Set to debut this month, it will include celebrity PSAs [see interview on page 13]. PR trade groups PRSA and PR Council are expected to unveil efforts this month to help communicators spread messaging in corporate settings. And a group of communicators debuted an effort last month to advise companies and organizations on vaccine-related messaging. [More on these below.]

The Opposition

Before examining messaging to mobilize support for vaccination, it’s important to understand what other hurdles communicators will face in spreading the message.

We mentioned months of mixed messages from the federal government, leaving a significant portion of the public distrustful of Washington and/or unconvinced that the virus is a threat to them.

Moreover, there are members and followers of anti-vaccination groups, which despite recent measures to curb their social media activity, remain a powerful force.

Another group is made up of those who’d prefer to let others get the vaccine first. Once it seems safe, they’ll get vaccinated. Misinformation or disinformation have caused some of this group’s concern. This narrative, though logical, might have been averted with better communication.

Lack of Transparency

Missing from Operation Warp Speed, the federal initiative to quickly find a vaccine and administer it, was a strategic communication component.

The public received scant reports about Warp’s process, knowing little more than that it was moving at an unprecedented pace. Without messaging from the government or the pharma companies, all sorts of narratives took hold.

One was rooted in common sense: Things done fast can be riddled with mistakes. In truth, much of the science in coronavirus vaccine development was completed years ago, to fight SARS and MERS. Had that story been communicated to the public, confidence in the vaccus might be higher.

In addition, during Warp there was little transparency from Washington and pharma about Black and Brown participation in vaccine trials, Dr. Nikhila Juvvadi, chief clinical officer, Loretto Hospital in Chicago, told NPR. This led to mistrust in the very communities the virus hit hardest. On top of that, for Black community members, the legacy of the amoral experiments done during the Tuskegee Syphillis Study and the use of Henrietta Lacks’ cells without her knowledge remains powerful.

In addition is the public’s declining trust in government, business, media and NGOs, according to the 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer. All had roles in vaccine development.

Another problem relates to timing. For months, videos and viral posts have circulated baseless claims about vaccines. For example, one holds that the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine contains tracking microchips that allow Washington to follow peoples’ movements. Now that the Pfizer vaccine is in the field, the company is beginning to fight back. It’s crafted messaging around the 10 ingredients in its vaccine. The conspiracists, though, had a large head start.

Yet another concern is rooted in science, but communication played a part. It holds that the vaccine may do harm to those with severe allergies. Indeed, after two British health workers developed adverse effects, regulators there initially recommended patients with severe allergic reactions not get jabbed with the Pfizer vaccine. Later they amended their language to patients with “a history of anaphylaxis to a food, medicine or vaccine.”

Communication around the two British cases was opaque. As communicators might expect, the result was confusion. That situation jumped the Atlantic when the Pfizer vaccine was granted emergency approval. The FDA is tracking anaphylaxis.

The last hurdle is political. Simply put, some people lack trust in a vaccine associated with President Trump. Another group may be reluctant to heed vaccination efforts of the incoming Biden-Harris administration since 77 percent of Republicans believe the 2020 presidential election was fraudulent, according to a recent Quinnipiac poll.

Data around vaccination is only a bit more encouraging. As noted above, the AP-NORC poll, from early December, days before the Dec. 11 FDA emergency authorization of the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine, showed about half of American adults saying they’d take the vaccine. Racial, gender and age breakdowns are significant [see chart, page 10].

A Gallup poll is more encouraging; 63 percent said they’d take a vaccine that the FDA approved.

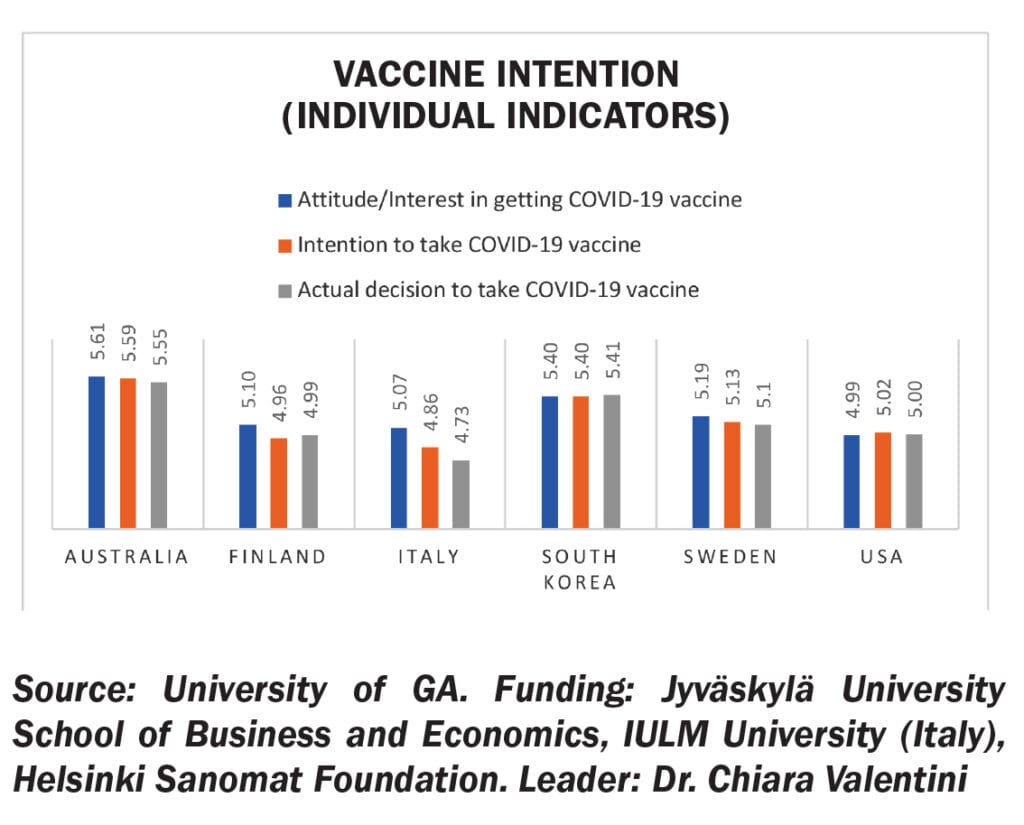

Where does that put the U.S. in terms of other populations’ attitude toward coronavirus vaccines? A survey of 500 adults in Australia, Finland, Italy, S. Korea, Sweden and the U.S. finds America on the lower end of vaccine attitudes, perception and behaviors, ahead of Italy only (see chart). Responses in the Jyväskylä University School of Business and Economics-led study were measured through a Likert-type scale, where 1 indicates “completely disagree” and 7 indicates “completely agree.” Part of a two-year study, the data is shared exclusively with PRNEWS. Overall, Australia (5.58) led, with S. Korea (5.40), Sweden (5.14), Finland (5.01), US (5) and Italy (4.89) behind.

Interestingly, there was little correlation between Italians’ trust in government and their intent to vaccinate. A better indicator, this study found, was between trust in media and intent to vaccinate. Besides Italy, U.S. trust in media was the lowest among countries in the study. Note there’s a lot of skepticism in Italy toward vaccines and their efficacy, with several anti-vaccine movements reaching a wide audience.

Other takeaways: age is a good predictor of vaccine intention, with older adults favoring vaccination; U.S. adults with higher income levels are more willing to take the vaccine; communicators should be mindful of cultural, education and demographic differences and tailor messages accordingly.

Into this difficult position come communicators. Despite the degree of difficulty, Gilman, who was recruited to lead a consultancy aimed at assisting companies and organizations about pro-vaccine communication, is ecstatic. “I haven’t done anything in years that’s gotten me more excited,” he says. Gilman likes tough assignments. He counseled Johnson & Johnson during the Tylenol crisis in 1982. Reaching herd immunity via vaccination, he says, will be harder than restoring trust in Tylenol.

While Gilman acknowledges the need for the sort of messaging the Ad Council will offer, he believes “the last mile” on health for most Americans is their employers. “The employer is their healthcare center,” he adds.

As such, the approach he’ll take with Project RESTART, the consulting unit he’s started to advise companies on vaccine compliance and other COVID issues, is to make vaccine acceptance similar to the Sabin sugar cube he took as a kid. “You have to make it something people want to do,” he says.

Most important, urging employees to get vaccinated, he says, should be an opportunity “for a company to build trust with its staff.”

A brief overview of Gilman’s approach includes:

•‘We care about your safety’: Companies should proactively send communication to employees, emphasizing staff safety is paramount. Avoid making this content cold and impersonal. Instead, use an empathetic, understanding tone.

•Determine the message: Decide what the company’s policy will be regarding vaccination. With herd immunity estimates at 75-80 percent of the population, do you want your staff at 100 percent, 95 percent vaccinated? Will you require proof of vaccination? What sort? Will you allow un-vaccinated employees to return to the office if 80-90 percent of your staff is vaccinated? If a staffer tested negative recently can he return to work without the vaccine?

• Choose the messenger(s)

•Get ready to answer difficult questions:What if employees believe they don’t need the vaccine? Perhaps their politics or belief systems put them among those who downplay the virus and the need for a vaccine? What about pregnant employees or those with health issues?

•Listen and diversify: Perhaps most important, be willing to listen to employee concerns and, of course, avoid belittling any. In addition, ensure your messaging is not tone-deaf via testing and by having a diverse, senior team create content and policies. Besides ethnic and gender diversity, get input from around the enterprise. “This could be a great way to build relationships with other departments,” Gilman says.

•Tailoring:Similar to every communication endeavor, there’s no one correct way to do this, Gilman emphasizes. Adapt the process to your company’s needs.

Late this month, PRSA plans to release an online toolkit, Voices for Everyone. It will include help for PR pros in identifying mis- and disinformation, including around the vaccines, says Michelle Olson, managing director and partner at Lambert and the new PRSA president. She envisions the crowd-sourced toolkit helping members identify false narratives around the vaccine. In addition, it’s expected to include examples of vaccine messages PR pros can tailor to the needs of companies they represent.

Facts Needed

The onus is on PR to spread “factual information” about the vaccine to counter what PRSA anticipates will be a mountain of false narratives, she says. Her assessment tracks with a recent report from Crisp. It points to at least 10 false anti-vaccine narratives floating around the internet. Claims include the vaccine causing infertility, death, narcolepsy and changes in DNA, among other dangerous things.

Another PR effort may be in the planning stages. In an interview in late December, PR Council chief Kim Sample confirmed rumors that the organization is considering an effort to combat the public’s vaccine hesitancy. The effort could include grassroots campaigns targeting school nurses and religious leaders, she told us. Data would help refine the campaign, she said.

Complicating things, Sample noted, is that some of the Council’s 110 agency-members already are doing similar work for “paying clients.” Still, she expressed enthusiasm and emphasized the need. “The public is so confused,” Sample says. She’s right.

The Ad Council’s 360-Degree Approach

With the CDC projecting 80,000 COVID-19 deaths in the first three weeks of January, there’s little doubt the country needs to shake off its vaccine hesitancy. An “all-points, 24-7 PR and ad campaign” must emphasize vaccine safety and build trust, says Andrew Blum of AJB Communications. It should include facts, but also plain language. In addition to celebrities, he says, real people should be featured in radio and TV PSAs. He also advocates a snail-mail effort and, where plausible, a Census-like activity, where citizens are approached about taking the vaccine. The Ad Council’s effort to wipe out vaccine hesitancy will include some of these elements, Lisa Sherman, president & CEO, tells us. Her responses were edited for space.

PRNEWS: What will the phases of messaging look like?

Lisa Sherman: A one-size-fits-all message is not the solution to a challenge as complex as mass vaccine adoption. We’ll have an air game and a ground game: the traditional media and placements...as well as grassroots, community and faith-based outreach...A core component will also entail uniting trusted influencers and messengers–including local doctors–to help Americans feel confident about getting vaccinated. Once our messaging is in market, as we do for all our campaigns, we’ll use a rigorous evaluation framework to measure our impact.

PRNEWS: What about diversity?

Sherman: We believe an education campaign is particularly important to ensure populations hardest hit by the virus are empowered with facts about vaccines.... Every step of the way, we’ll be guided by campaign research. We’ll reach diverse audiences through strategic media placements, culturally-relevant content and community-based outreach.

PRNEWS: How will you build trust?

Sherman: We recognize that there is currently a lack of confidence and credible resources for people to go to for the vaccine, leading to mass hesitation, fear, misinformation and complacency. We’ve found that the messenger can be just as important as the message itself. We know working with trusted messengers and influential voices will be another key component of the effort.