Having an extensive social media strategy is a key part of crisis readiness. In addition, it can help a company take advantage of a breaking situation that falls short of crisis.

A healthy social media plan starts with listening—keyword research, daily roving of consumer sentiment and a constant audit of your organization’s stance on current events.

Next comes preparation for any type of scenario and a process for going forward with a variety of responses—especially if you have a product launch or an event approaching.

This is were it can be helpful to have a social media war room in place, a team dedicated to responding to an event in real-time. At a minimum, having social media experts and content creators on hand can make a difference.

Remember the Super Bowl blackout in 2013, and Oreo’s perfectly-timed tweet? People are still talking about it.

Business Debate Show Host

ProveItMatters.com

“While the stadium was covered in darkness and confusion, we saw an opportunity to make cultural commentary and to jump into the national conversation with relevance and speed,” says Leo Morejon, social media professional and Business Debate Show host at ProveItMatters.com. Morejon was lead social media community manager for Oreo at the agency that represented the brand.

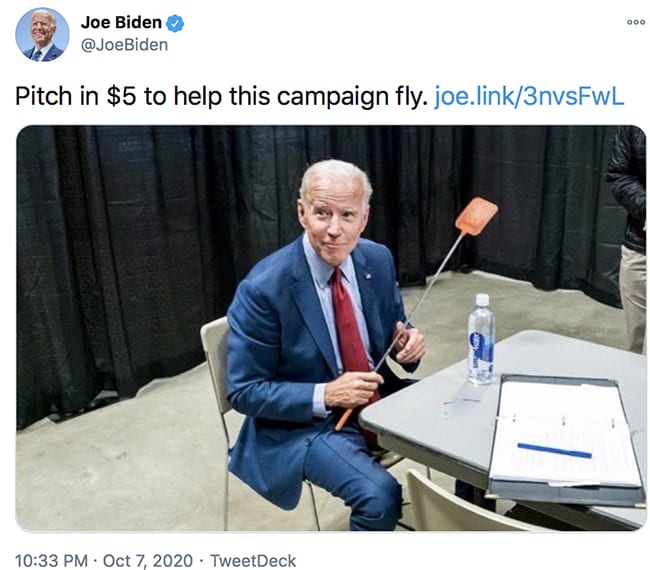

And, though it was hardly a PR crisis, former Vice President Joe Biden’s campaign had fly swatters for sale within minutes of an insect landing on Vice President Mike Pence’s hair during the VP debate last month.

A timely response is not always a coincidence. For most social media professionals, plans for a potential situation are created months in advance. We talked to several pros about social media war room best practices.

Situation: Election

Audience Engagement Editor for Politics

The Los Angeles Times

Adrienne Shih, audience engagement editor for politics at The Los Angeles Times, has been preparing for Election Day for weeks. Shih even wrote an article telling readers how the newsroom will be covering this year’s election.

At a news organization, war room teams come with a lot of experience. In pre-COVID-19 times, Shih says, reporters and editors gathered in a physical room every time there was a major event to process real-time updates.

For the 2020 election, Shih and the team have done much of the legwork ahead of schedule, as well as planned for unforeseen events.

“Sometimes, even for huge tentpole events, you have the ability to plan certain elements,” Shih says. “In advance of Election Day, I compiled a giant spreadsheet of our past coverage, assigned specific tasks for the night of and made sure to train all of our teammates. A team leader should assign everyone a very specific, actionable task, so that all bases are covered.”

Shih emphasizes the importance of transparency, particularly within the news industry, during what could be a long election night—where results could take days or even weeks to confirm.

“It’s always best to be transparent with your audience, and to signal that you’re working on clarifying or confirming facts in a rapidly changing situation,” Shih says. “There’s nothing more dangerous than confirming speculation, unless you really do have a certain answer. Otherwise, you’re just adding to the noise of disinformation.”

Situation: Faculty Strike

Communications Director

Association of Pennsylvania State College and University Faculties

Kathryn Morton, communications director for the Association of Pennsylvania State College and University Faculties, spent three days in a war room during a 2016 faculty strike. Her small state staff included herself and the government relations director. Morton did everything in her power to stop a social media flood for 14 campuses.

“When tweets and Facebook messages started gushing in the night before the strike, [we] split up responding to questions and comments,” Morton recalls.

The team started a file of frequently-used responses, so they weren’t typing from scratch each time, and it helped to keep messaging consistent, Morton adds.

“Many of those social-media responses derived from talking points and FAQs I’d been posting and updating in the months leading to the strike,” she says.

War room satellite offices included members of the 14 campuses who took on social media duties for their chapter accounts.

Morton found preparation to be key for the strike, which most PR pros know usually doesn’t happen overnight. It included extensive media training for staff outside of the war room. The month before the strike, the organization held a strike school to train team members “in everything from how to organize picket lines to my area of social media,” Morton says.

Morton also believes a company’s social accounts should set a precedent of trust before a crisis occurs.

“For an unexpected event, I’d identify who will do what during an event, even if you don’t know what your content will be,” she says.

“You’ll waste precious time if you’re scrambling to figure out who’s going to post on what channels—or, worse, if you’re scrambling to create new accounts. Followers can blow up overnight, but your credibility and reach will be higher if you’ve been developing a relationship through your posts before the emergency or event occurs,” Morton says.

Situation: Potential Active Shooter

Communications Advisor

Piedmont Environmental Council

Unfortunately, active shooters have become a part of the crisis lexicon. While working at the University of Rhode Island, Cindy Sabato, currently communication advisor for the Piedmont Environmental Council, became aware of a suspicious tweet while monitoring social media.

The tweet read, “What just happened in Chaffee Hall that everyone sprinted out of the building scared s---less?” The events following unfolded on social media accounts, primarily Twitter, due to its reputation for rapid response.

“While social media is a tremendous means of rapid communication, it is also frequently a victim of well-intended rumor, misinformation, miscommunication, confusion, and information overload that can lead to chaos and pandemonium,” Sabato says. “Initial social media reports were of an active shooter, combined with some accounts of a student or students standing up in a lecture hall and making threatening statements.”

Over time, active shooter became “someone with a gun,” and later someone who “might have had a gun,” to “it was a campus-wide Humans vs. Zombies game,” Sabato recalls.

Regardless of the outcome, Sabato’s group rightfully took every piece of information on social media seriously. Sabato believes having everyone in one place and tackling the same situation accounted for the University’s accountability that day.

“Having everyone together in the same space allows for consistent messaging that is approved by an official spokesperson,” Sabato says. “That person...ensures messaging is accurate. And someone dedicated to each mode of communication gets these consistent and accurate messages out quickly.”

Even when the situation is unfolding in real-time and there is no clear message at the outset, letting people know that you’re working on it is an important strategy.

Sabato agrees that timeliness is key when dispersing information, even if it is only an update that authorities are working on the situation.

“If an organization has social media accounts, its community will expect it to be social, to be present in that space,” she says. “Failure to do so puts the organization’s credibility at risk.”

Being able to send out consistent information reduces the risk of disinformation or rumor dominating the narrative. It also puts stakeholders at some level of ease. Staying silent is not an option.

“Understand and commit to the fact that social media will be the public’s primary source of information in the crisis, and if they are not getting it from you, they’ll get it from [elsewhere],” Sabato says.

Much like the adage to never or rarely say No comment, Sabato recommends, “in a crisis, never say nothing.”

Contact: [email protected]

Best Practices for war rooms

Experienced pros share their tips for what makes a successful war room, whatever the situation.

Take notes. As soon as possible, jot notes about what worked well and what didn’t. Save any FAQ documents you created, advises Kathryn Morton, communications director for the Association of Pennsylvania State College and University Faculties.

CEO

Beanstalk Predictive

Remember the team. While covering live events can be exhilarating, it is critical to remember they can also be excruciating for the team. As such, plan for regular staff breaks. Use the 80/20 rule, where 80 percent of posts are pre-scheduled, while 20 percent remains live and unplanned, suggests Matt Murphy, CEO of Beanstalk Predictive.

Prepare physically and mentally. War rooms can be nerve-wracking—even for the seasoned professional. Brands need to cast teams correctly. Team members need to prepare emotionally. “That includes being open to the possibility of anything happening; good, bad and/or the ugly,” says Leo Morejon, Social Media Professional and Business Debate Show Host at ProveItMatters.com.

Social Media Manager

CareSource

Staff properly. The only really good war rooms are those that utilize graphic designers who know the brand standards. Ensure they are in the room with the person managing the community. “Always have a person who gets to say ‘go/no go’ [who is] close to the community,” says Sarah Chapman, social media manager, CareSource. Having a full committee means it is going to be slow going and turn out mediocre work. “Take some big risks. If you make a couple people in the room uncomfortable, it’s probably the right idea,” she says.