One of the few certainties during the period we’re living in is how uncertain it is. That makes communication more complex. Communicators know flexibility and adaptability are vital in message creation at a time of potential global political instability, inflation and possible recession, supply chain hang-ups and a pandemic that lingers. Still, even experienced communicators stumble.

There are few things more uncertain than COVID. Even as mask mandates are lifted, the virus pokes through. For instance, at our press time, media reports warned of rising COVID levels in NYC. Certainly, COVID infection rates, hospitalizations and deaths are not at previous levels there. Still, NYC health officials are urging additional caution. And they are considering reauthorizing indoor masking.

"We know a lot more about the virus now than we did in 2020, and businesses have learned to adapt," says Katherine Harris Griffith, VP, Elizabeth Christian PR. Still, she concedes, "It's important for companies to pay attention to the virus and what it's doing in the communities they serve...this is our new normal."

Confusion around COVID even caught one of the federal government’s best communicators, when White House chief medical adviser Dr. Anthony Fauci faltered recently.

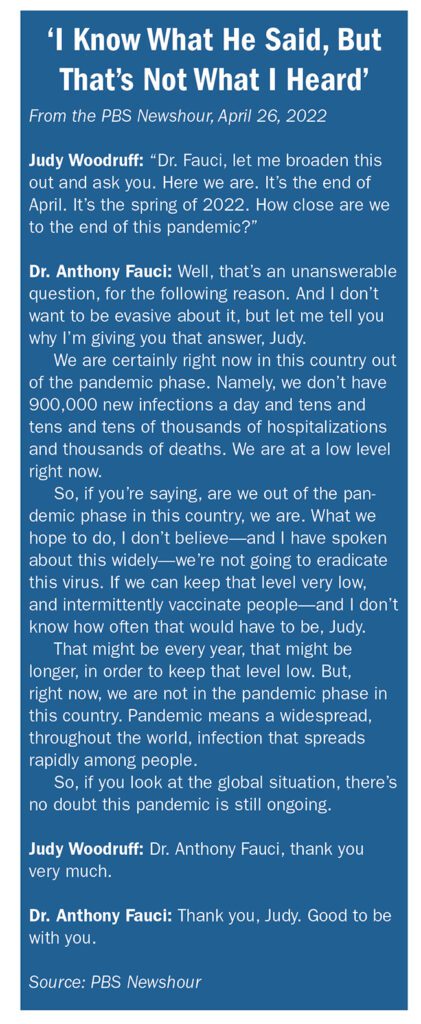

On April 26 Dr. Fauci said on the “PBS Newshour” something that sounded like the pandemic is over. At least that’s how some, including those doing other things while the Newshour played in the background, may have heard it.

Indeed, media outlets grabbed an excerpt from Fauci’s remarks. Their hastily assembled news reports concluded that yes, Dr. Fauci says the pandemic is over. It was another confusing moment in the brief, tangled history of COVID messaging.

'What did he say?'

In fact, what Dr. Fauci said wasn’t wrong [see full text in the box below].

The pandemic phase of COVID is over in the US. Yet, the pandemic remains, as waves of infections remain possible. Fauci clarified his remarks the next morning for the Washington Post. “The world is still in a pandemic. There’s no doubt about that…we are still experiencing a pandemic,” Fauci told the Post.

Still, his words on PBS were easily misinterpreted. Andrew Noymer, an epidemiologist at the University of California at Irvine, told the Post, “As soon as I heard [Dr. Fauci’s pronouncement], I figured it would be wildly misinterpreted by your average member of the public.”

Dr. Fauci is not alone. Just days before his initial remarks, Delta (the airline, not the variant) also misspoke. Its statement announcing optional masks flopped, when it downplayed COVID’s current state as “an ordinary seasonal virus.”

Following a social media hubbub and White House pressure, Delta, like Fauci, re-spoke. The next day (April 19) Delta labeled COVID “a more manageable respiratory virus.”

Takeaways

PR pros know several maxims apply in these cases:

- At times, executives will act alone, saying things in public that depart from communicators’ careful scripts. It’s unclear what happened with Delta, though some executives, anxious to get rid of masks, allegedly were using the phrase “ordinary seasonal virus” prior to the airline’s mask announcement.

- What an executive says and how the media reports it (and what the public hears) sometimes are different. The resulting confusion leads to the next maxim.

- The best chance of conveying your message exactly as you want is via owned media. Of course, the public and media could misinterpret your message anyhow. That’s because…

- The public isn’t always concentrating on every word or nuance in your message. And, as above, the press interprets your message as it wishes. Still, we know…

- Words matter, especially when discussing something as confusing and uncertain as COVID, which Delta Airlines discovered, to its embarrassment.

What to do?

Considering the above bullets, confusion about communication seems endemic, pun intended. And, as noted above, COVID and other quickly occurring changes almost are routine.

As such, communicators, as they do for PR crisis, should consider preparing for myriad eventualities. It seems logical–if not downright practical–that communicators spend time regularly crafting tactics and strategies they can use as responses for what if scenarios.

As noted, traditionally some communicators engage in scenario planning as preparation for PR crises. "All companies find themselves in need of a solid crisis communication plan from time to time," says Tiffany Rafii, co-founder, UpSpring PR. "Where possible, have a crisis plan in place ahead of time and make that plan visible," Rafii adds.

However, it might be time communicators augment their planning routines, injecting them with a dose of futurism.

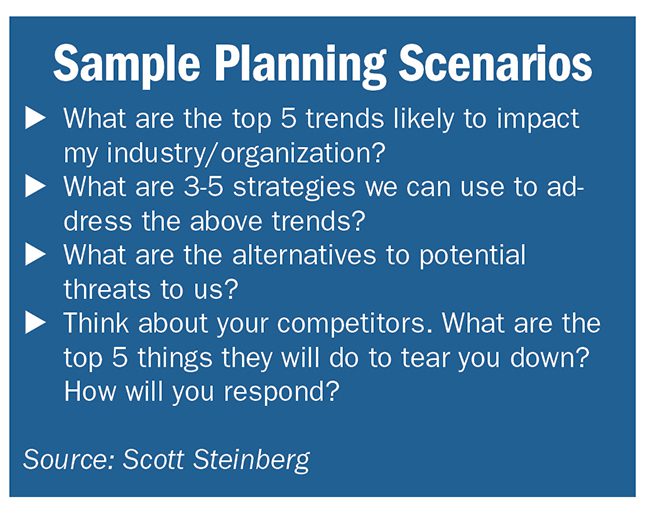

The world is moving too fast for “purely reactive communication anymore," futurist and author Scott Steinberg argues during a PRNEWS interview. Communicators, he adds, should emulate legal and business analysts, who routinely craft responses to potential future scenarios.

Hold on. Avoid dismissing the argument because of the word future. The suggestion here is that communicators, as part of their duties, plot messages that respond to a range of potential issues. It's not as difficult as you might think.

In a sense, we know the future

For example, Steinberg says, we don’t know exactly how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will end. Still, “we have a sense of a potential range of outcomes...an idea of what things might look like” and what it could mean for businesses.

Steinberg suggests other what if questions that seem germane now:

- What if COVID surges again and pauses our return to office?

- Similarly, what if we hold an event and it results in a rash of infections?

- What if geopolitical issues result in further supply chain disruptions? What does that mean for our business? Our competitor’s business?

- What if more states react like FL did when corporations take political stands?

- How do we respond if the government upends our plans for a crypto business?

- What if our competitor gains a technological advantage over us?

- I’m in oil or gas. What happens if overnight regulations change toward cleaner energy? How are we going to reassure the general public and press that there’s still a future for our company?

While a self-described futurist, Steinberg doesn’t pretend forward-thinking is a panacea. “You can’t always control what direction the future will go,” he admits. However, “you always can [try] to steer things toward a more positive outcome.” Isn't that a decent description of the communicator's remit?

Think like a futurist

In addition, Steinberg contends any communicator “can train to think like a futurist.” He adds quickly, “futurists don’t predict the future. We map out trends that are percolating in society and challenge" others "to think about how they might impact their business.” A good futurist, Steinberg believes, reminds people “they have most of the answers already.”

Yes, we know what you’re thinking. Sounds good. But I barely have time to finish what’s in my inbox. You want my team to spend time creating responses for situations that don’t threaten us yet? In short, yes, Steinberg says.

Ironically, Steinberg draws on crisis preparation in bolstering his response. “If you don’t take a little time to plan for tomorrow, it’s going to get here very quickly. Better to greet it prepared.”

In theory, PR pros concur with the futurism approach. However, it's a matter of time management.

For instance, Kyle Monson, founding partner at Codeword in New York, encourages businesses he represents to craft plans for "four or five" disruption scenarios. "Executives sleep much better knowing there's a plan...a button to push," Monson adds. Such plans should emphasize transparency and other company values, he says.

Similarly, Griffith believes companies must budget time for scenario planning for current initiatives. "While we're living day-to-day in a pandemic, businesses need to give as much time as possible to plan communication initiatives for events, including contingency plans for in-person events," Griffith says.

While Monson spends a lot of time working with companies on disruption plans, he believes nobody can anticipate every threat or change scenario. "Who could have seen COVID coming and then leading to the Great Resignation and inflation?" he says. Still, having multiple responses in place "allows companies to improvise," depending on the challenge. "You can move from jazz to classical music."

On the other hand, Monson says, there's a planning limit. "You can get yourself tangled up examining too many scenarios...you don't want to spend too much time down that rabbit hole."

20-30 percent daily is ideal

Accordingly, we ask Steinberg what sort of time commitment he is advocating. “It is a moving target and I realize communicators have more to do than ever. But, ideally, the hard, fast rule is 20-30 percent of your day.”

He admits that sounds like a large number. But, he argues, if you use the same PR approach today as you did yesterday, “and ride it till the wheels fall off, well, you may end up where you’re headed…as the world changes constantly around you.”

As noted above, what Steinberg advocates sounds similar to preparation for crisis communication, another activity many executives (and a few communicators) dismiss. It will never happen to me, so why spend time preparing for a PR crisis?

Similar to PR crises, future scenarios, as noted above, are hiding in plain sight and read like a survey question. Where will the next disruption come from? Economic issues, cyber, supply chain, crypto, the metaverse, NFTs, political instability, global health emergencies.

Hide or prepare?

Like crisis preparation, the question about considering future scenarios becomes “will you bury your head in the sand” or, suggests Steinberg, say, ‘Well, we don’t know what direction the future will take. But we’re going to plan around a variety of different directions. This will leave us the flexibility to change tack as we go.’”

But, what if your scenarios fail to occur; have you wasted time? Steinberg sees benefits. He argues scenario planning is a muscle. You’ve exercised it “and trained yourself to apply critical thinking and dynamic decision-making…this makes you better prepared” to adapt if and when a major change occurs.

We’re in a period where the pandemic seems over. Surely that’s opened communicators’ eyes to the importance of considering the future. Maybe. Both Steinberg and Monson think communicators now inherently are more aware of the importance of scenario planning. Monson believes this is so for senior communicators especially. Yet he's unsure how much the pandemic’s resulted in a wider appreciation for planning outside the highest levels of companies.

Similarly, Steinberg says many communicators must “get permission” to stop what they're doing and engage in the type of scenario planning he advocates.

The good news, Steinberg says, is that while dedicating time consistently for scenario planning can seem like a large undertaking, making a few small changes can yield large returns. Moreover, a minor investment, made consistently will compound, he says.