It’s not news that brands and communicators live in a fast world, with quick news cycles. And no doubt you have heard maxims on the theme that social media, in a few seconds, can destroy the reputation a brand has built carefully over many years. On the other hand, a lightning-fast news cycle also can be a blessing for brands. News stories become old quickly, so an unpleasant item about your brand may be part of the zeitgeist for a few hours and then recede from public consciousness. The question for communicators, of course, is how quickly to respond or not respond?

There were several examples of this last week. A teen in S. Carolina lost his life in late April due to ingesting too much caffeine too quickly. The story hit national news May 15 when the coroner confirmed the cause of death of David Allen Cripe, 16, as “a caffeine-induced cardiac event causing a probable arrhythmia.” News reports said the caffeine came from Diet Mountain Dew, a McDonald’s café latte and an unspecified energy drink. As of this writing, none of the brands named has commented.

EVP/CCO,

Bell Helicopter

Another example: The wife of New England Patriots’ star Tom Brady seemed to imply during an interview with CBS This Morning May 17 that her husband had suffered concussions last season. No official reports of such injuries to the marquee player were filed during the season, however. The issue here is that the National Football League has strict rules prohibiting concussed players from participating in games and practices. Speculation ran rampant May 17 and 18, mostly on sports blogs, about whether or not Brady had hidden concussions from league officials. About 8 hours after the story broke, the NFL responded that it had “reviewed all reports relating to Tom Brady” from various medical personnel and “there are no records that indicate that Mr. Brady suffered a head injury or concussion, or exhibited or complained of concussion symptoms.”

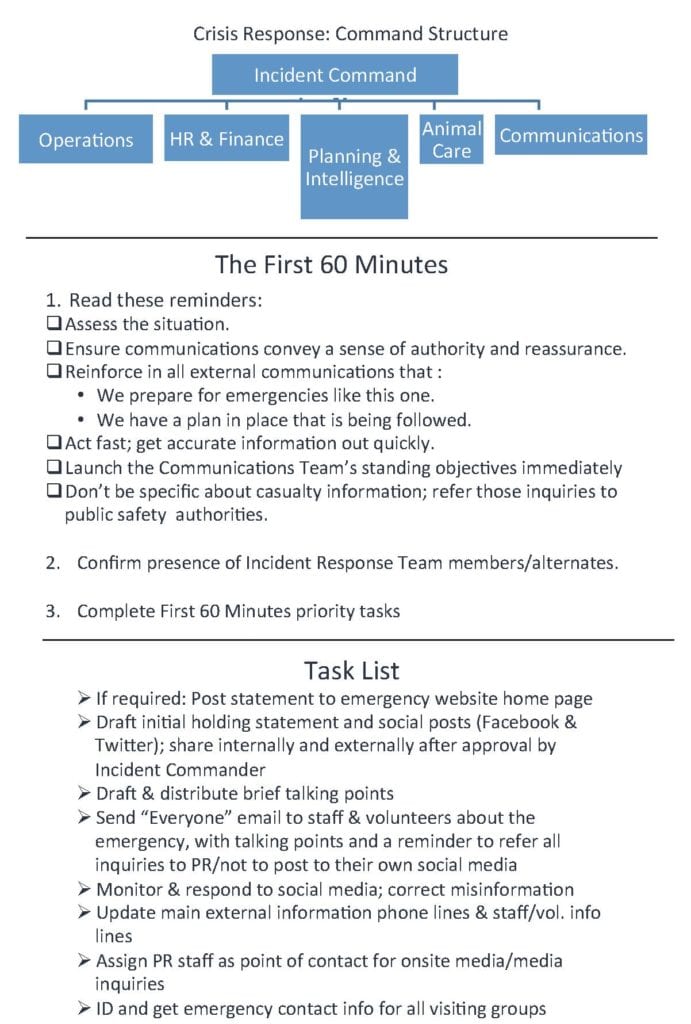

Evaluation: These situations prompted us to ask communicators about responding to and planning for crises. Both Ken Peterson, communications director of Monterey Bay Aquarium, and Bell Helicopter CCO Robert Hastings urge brands to include an evaluation process in their emergency plans to determine whether or not a situation is a crisis. This evaluation process should include monitoring social conversations and news coverage. That’s step 1 at the Aquarium, Peterson says. Step 2 is an initial assessment to “ramp up or stand down.” Should the decision be to ramp up, a pre-determined incident response team [see top chart] assembles in an extensively equipped crisis room and begins “acting on standing objectives.” Designated individuals communicate with media, stakeholders and the public. As things can get out of hand quickly, during the first 60 minute a series of reminders is read [see middle chart].

A tip: Peterson urges brands to designate a backup crisis room(s) in case circumstances render your main crisis room unusable. Also have a backup plan for your crisis plan. “Even the best plan will hit bumps,” he says. Adds Hastings, redundancy in every aspect of crisis is critical, including personnel. “It’s Murphy’s Law (that the person you want to be on site during a crisis won’t be)…so you need to train backups.”

Practice: It’s accepted that a crisis plan is less effective without regular practice sessions. The Aquarium uses a table-top crisis training exercise that lasts 6-8 hours, Peterson says, and budgets $30K-$40K annually for crisis preparation. The institution’s annual budget is $100 million.

Mobilize and Alert:Hastings insists on using the term “incident management” as opposed to crisis communications. He perceives his team’s job during a crisis as following “deliberate action plans to mobilize management…and get it the right information.”

Mini Case Study: Within three minutes of the crash of a Bell helicopter and the death of two employees, a push system alerted all managers. In addition, a pre-determined group of senior executives had self-selected a leader to oversee the situation. As Bell is a global company, senior executives are travelling constantly, thus the need for senior execs to be able to self-select a crisis captain.

Next Steps: As a result of the pushed alert, senior representatives of communications, HR, legal and other units gathered within minutes, Hastings says. There they divided information into several categories, including what we know, what we don’t know and what we will release to the media and public. Soon after, the media was told what Bell knew, what it didn’t know and when the first media briefing would be held. Teams were sent to the homes of the deceased employees immediately to brief the families, he says.

Closure: Hastings urges brands to plan for when they want to return to normal after a crisis and announce it. In the case above, Bell told the media on day 3 “we’re done treating this as an emergency,” Hastings says. Peterson adds that brands need to plan for a crisis that endures for “a week or longer…this is where redundancy also is needed.”

Note: This content appeared originally in PR News Pro, May 22, 2017. For subscription information, please visit: https://www.prnewsonline.com/about/info

CONTACT: @aquaken [email protected]