There’s one thing you can say about social media–sometimes it helps remove doubt. Before social media, person A could allege that he heard person B utter racist remarks. Today, after making such an allegation you can assume someone, a media member, perhaps, will scour person B’s public-facing social posts for supporting evidence.

It goes to a principle that communicators know well: Nothing disappears once it’s posted on social media.

Post something that enough people consider insensitive and you can find yourself on the wrong side of an onslaught. Ask Burger King UK.

Posts Can Live Forever

Let’s complicate things. Say a person posts something insensitive and out of character. Add another wrinkle: the poster is young and immature. Years later, the post may resurface and cause her trouble when she’s up for a big job.

True, if trouble flares from the old post she, as an adult, can pull it down. With the help of communicators, hopefully, she will issue an apology. Perhaps those steps will reduce some pressure. In addition, she can cancel her social media account, as some celebs have recently.

Evidence of what she posted as a teen still exists, though. Chances are someone has taken a screen grab of the offending content. There’s also the possibility a media member is writing about it. Some sites do nothing but collect images of controversial posts that were pulled.

‘My Vaccine for a Clear Online Presence’

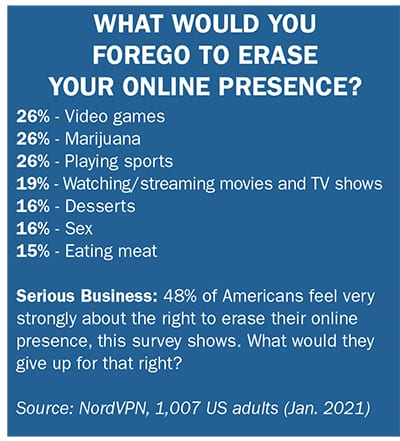

This sort of scenario is far from an issue reserved for celebs and those seeking top jobs. 93 percent of Americans believe they should have the option of having websites delete or forget their online presence, a recent survey from NordVPN shows. Nearly half (48 percent) of the 1,000 adults it surveyed in January felt “very strongly” about this.

How strongly? 28 percent would forego alcohol if they could wipe their online presence. And 18 percent would give up COVID-19 vaccination [ see chart on p. 2].

Let’s broaden our scenario. Consider a person who’s accused of bad behavior. Suppose the person has a high-profile position and is accused of making insensitive remarks and committing sexually harassing acts. The wrinkle, though, is he did all this years ago, well before the company hired him.

But someone comes forward to say that 10 years back this employee behaved badly. Next, more people, again from previous employers, make similar claims publicly about the person.

As a communicator at the company that currently employs this man, do you remain silent? Wait for more allegations? After all, these acts allegedly occurred years before this man became your employee.

On the other hand, your company’s HR team recruited and hired this employee. Did its staff know about these accusations? Was due diligence more than a quick check of his résumé?

Let’s say HR discovered dissonance in the employee’s history. Did it hire a company to do a background check? Perhaps the worst-case scenario for your company is that it knew about the accusations and hired him anyway.

Real Examples

The above are more than potential scenarios. Each include elements from recent events. They offer a bevy of lessons for communicators.

Parts of the teen tweet example are culled from the story of Alexi McCammond, 27, who was set to become editor-in-chief at Teen Vogue late last month. McCammond rose to fame at Axios, where she covered the presidential campaign of Joe Biden.

As a teenager at the University of Chicago, McCammond posted a nasty tweet about an Asian teaching assistant who’d given her a poor grade. Other anti-Asian and anti-gay posts also flowed from her keyboard during college.

While at Axios, in 2019, she apologized for the posts. Still, in the midst of a rise in attacks on Asian Americans, 20 staffers at Teen Vogue rebelled against McCammond’s announced hiring, citing her old tweets. Others joined.

McCammond apologized again and executives at Condé Nast, Teen Vogue’s parent, came to her defense. Still, on March 18, nearly two weeks after she was named editor, McCammond and Teen Vogue decided to “part ways.” March 24 was supposed to be her first day in the prestigious post. Some see it as the height of cancel culture. Indeed, one newspaper column headline blared, “If Teen Vogue can fire an editor for her teenage tweets, no one is safe.”

Bad Behavior at PreviousJob(s)

To say Les Miles was a revered football coach at LSU (2005-2016) is an understatement. His record was 114 wins, 34 losses, a winning percentage of.770. Miles took the team to 12 bowl games and won the college championship in 2007, only the 3rd in LSU history.

He was known for being loyal to his players. In addition, he insisted his athletes take academics seriously and graduate.

Two years ago, The University of Kansas hired Miles before the 2019 season. After two seasons, his record at Kansas was just 3-18. Though Kansas has won more than three games in a season once since 2009, perhaps Miles’ won-lost record was enough to fire him. Still, his football prowess did not prompt the coach’s March 8, dismissal. What follows is a textbook example of how to mishandle a toxic situation. It also illustrates the fallout a botched crisis can have across multiple organizations.

On March 4, LSU, his previous employer, released an internal report it had done in 2013. Previously unpublished, the report details a 2013 internal investigation of Miles, who allegedly was inappropriate with female student-employees of the athletic department. The report mentions Miles texting female students, inviting them to his condo, making them feel uncomfortable, among other things.

Despite this, Miles coached three more seasons, and part of a fourth, at LSU.

After the 2012 season, his eighth, Miles received a raise. At $4.3 million, he was the state of Louisiana’s highest-paid employee.

Late in February 2021, USA Today broke a story about the 2013 investigation. Through his attorney, Miles said the report exonerated him. After all, he’d continued to coach at LSU.

One day after confirming USA Today’s story, LSU released another report about Miles. The school initiated this report in late 2020. It includes interviews with 50 current and former LSU stakeholders: students, employees and others. In a display of transparency, the school posted the report online.

Its bombshell was that Joe Alleva, LSU’s athletic director, recommended firing Miles in June 2013. Included in this new report, Alleva’s email to the school’s legal team and incoming president should resonate with communicators.

After the 2013 investigation, Alleva ordered Miles to steer clear of female students. In the email, Alleva alleges Miles ignored his order.

“I want us to think about which scenario is worse for LSU. Explaining why we let [Miles] go or explaining why we let him stay,” Alleva writes in the email to school leaders, including incoming president F. King Alexander.

“I believe he is guilty of insubordination, inappropriate behavior, putting the university, athletic dept and football program at great risk,” he adds. “I think we have cause. I specifically told him not to text, call or be alone with any student workers and he obviously didn’t listen. I know there are many possible outcomes and much risk either way, but I believe it is in the best interest in the long run to make a break.”

Email Ignored Initially, But...

Alleva’s 2013 email plea worked, though it took eight years.

On March 6, Kansas put Miles on administrative leave. Two days later, Miles and Kansas agreed to “part ways.” A brief statement from Kansas mentions nothing about the LSU reports.

Similar to LSU, though, Kansas had a fit of transparency. It posted the legal document detailing Miles’s departure package of nearly $2 million. A better response would have included transparency about how Miles was hired. That didn’t happen, at least not immediately.

Jeff Long, the Kansas athletic director who hired Miles, said March 8, “I am extremely disappointed for...everyone involved with our football program...We will begin the search for a new head coach immediately with an outside firm to assist in this process. We need to win football games, and that is exactly what we’re going to do.”

Days later, Kansas booted Long. Though a departure statement praised him for being “unwaveringly dedicated to students, coaches and staff” and “represent[ing] KU with integrity and compassion,” the rap against Long, which went unmentioned officially, was that he’d done little due diligence before hiring Miles.

What makes the Miles incident an even better example of crisis incompetence is that the fallout extended beyond Miles and Long. It hit another institution. Several weeks after Long’s ouster, on March 24, Alexander, the former LSU president, resigned abruptly from his post as president of Oregon State University; he’d been there nearly one year.

Implications For Communicators

These stories’ implications for communicators are many. First, it’s advice that seems obvious today–but wasn’t 10 years ago, when McCammond created her posts. “It’s something that nobody wants to hear, but be careful when you’re using social,” says Mike Paul, president, Reputation Doctor, LLC.

Second, communicators should ensure there is recognition at their company of the ties between hiring and PR crisis. With so many PR crises stemming from human misbehavior–ethical lapses, poor decision making–it makes sense to put time and effort into due diligence, Paul says. “The tools to [look into people’s past actions] …have existed for a long time,” he adds. They’re more plentiful in the digital era, of course.

For example, when Nicole Dye-Anderson, VP, head of partnership media relations/DE&I and PR at Barclays, receives a résumé, in addition to scouring the candidate’s social posts, she insists on checking what they’ve ‘liked’ on social. The social posts a person creates may be pristine, she says, though the topics they favor with a ‘like’ may tell a different story about who they are.

Hiring Procedures Are Key

Digging deeper on hiring practices, particularly for high-level candidates, Paul advises communicators check whether or not their company goes beyond due diligence.

For example, does it employ an outside firm to “gather intelligence and find information that’s not easy to uncover?” he asks. It appears this didn’t happen with Kansas’ hiring of Miles.

Paul’s thinking is that since so many PR crises stem from human issues, hiring procedures are akin to a first-line of defense in crisis prevention.

When an organization fails to place a premium on how they pick people–asking tough questions about ethics, morals and decision-making–it is opening itself to a PR crisis, Paul adds.

Ironically, when a company hires an outside firm to conduct background checks on potential candidates it is ‘purchasing’ insurance in case of a personnel-type crisis, Paul says. Should a crisis occur, your company can pin at least part of the blame on the outside firm’s failure to do a thorough job vetting the person at the center of the crisis.

Notice that when then-Kansas Athletic Director Jeff Long said the school was launching a search for Les Miles’ replacement, he mentioned that it will hire a company to conduct the search.

Best Case, Worst Case

In the McCammond example, Teen Vogue executives claim they were aware of her posts and 2019 apology. Where they seem to have miscalculated, Paul says, is they looked at the best-case scenario, which was that McCammond apologized in 2019, survived and thrived at Axios.

Instead, he says, they should have considered the worst-case scenario: “That people would re-position her [social media content] in the current context” of sensitivity about the rise in anti-Asian attacks.

Context At ‘This Moment’

Dye-Anderson has a different view of the McCammond example’s implications for PR pros.

“As communicators, we’re taught to ‘Acknowledge, Apologize and Address,’” she says. You acknowledge there’s an issue, you apologize, you take an action to show contrition–perhaps a donation or public service–then you implement a plan that demonstrates the problem won’t recur.

In the McCammond case, though, the 3 A’s formula didn’t work, or more correctly, it wasn’t given time to, since McCammond and Teen Vogue decided to part ways.

For Dye-Anderson, it’s possible the 3 A’s no longer work, at least during this polarizing moment in the midst of cancel culture. “If that’s true, we’re in very dangerous territory” because it means a youthful mistake can never be forgiven, Dye-Anderson argues.

Part of this moment, she argues, is that people are talking more about race and inclusion and, hopefully, adding perspective to their thinking on the matter. In other words, it’s a time to hope that people are becoming more attuned to diversity, equity and inclusion than they were when they were younger.

In addition, she believes just about everyone has something in their past that they’d prefer not to expose. Indeed, nobody is safe.

For Dye-Anderson, society needs to come up with a standard as to what sin “is unpardonable.” Can’t society pardon someone who’s made mistakes as a youth and has since atoned? she asks. “It’s different if you are an adult, or in a position of power, when you made the mistake,” she says.

She admits, though, “You can’t remove emotion from the [Teen Vogue] situation...people were very upset with those tweets, and rightfully so.”

For Jenny Wang, VP at The Clyde Group, the critical part of the 3 As is the action. “The most important thing–no matter what a company may or may not choose to do in instances like this is that authentic ACTION–not just words–back up apologies and expressions of contrition.”

She suggests that the action may look different depending on the instance (pledging to provide and take educational courses/workshops, making a meaningful donation, etc).

Since the McCammond example involved the actions of a college student, we asked a college student studying PR for her take.

Laura Burr is a senior at the University of Georgia. She’s studying PR and minoring in fashion merchandising. She feels McCammond wasn’t strong enough in her 2019 apology. “It didn’t mention the word ‘racism,’” she says.

Maybe the public perception was [McCammond’s] apology wasn’t public enough, says Dye-Anderson.

That leads to another point, Paul says. In this moment, it’s not just media criticizing those who’ve made mistakes. “It was a journalist who resurfaced her tweets. It was a Teen Vogue staff member,” he says.

Offensive posts or other bad acts, regardless of when someone committed them, “are part of you for the rest of your life,” says Paul.

When he’s advising someone, who’s apologized for a significant mistake, ancient or not, “The first thing I say is, ‘Good job. Now, be prepared to do that for the rest of your life.’”

So, is someone like McCammond marked for life? Paul doesn’t think so. Neither does Burr,though she supports companies taking a strong stand on youthful mistakes. She feels today’s college students know the implications of social media posts, though she admits McCammond’s generation, 10 years ago, had less of an idea about such things.

Paul advises McCammond or others in similar situations to get polling done “to see if people still like her and empathize with her situation.” If it’s positive, she could use the data to get her next job, he argues.

Burr’s advice is that McCammond write freelance articles explaining her youthful mistakes and urging others of the dangers. “It’s not so much that she created those posts, but that she had those sorts of thoughts,” Burr says. That’s what companies need to consider, she says.

Honesty

And if a person has bad behavior deep in his background, should he disclose that information during a job interview? It’s risky, Paul admits, though if you’ve “done your time or [if it’s an addiction and you’ve] been clean for a long time” it’s in your best interest to be honest at the interview, he says. “It’s the only way to build trust.”

He uses the example of a healthcare employee who’s remained clean after a drug addiction. Admitting that you’re in recovery, he says, puts you in a great position to provide authentic advice to others battling with addiction.

Several communicators, including Dye-Anderson, emphasized McCammond might have preempted things with ‘a roadshow.’ For example, her hire announcement could have included plans for McCammond to do a series of stories on how important it is for teens to be careful on social media. “She was a teen when she posted,” Dye-Anderson says. As such, “she could have brought authenticity to those stories.” It’s similar to Paul’s healthcare example.

Paul agrees. “It could have been a teachable moment. Teen Vogue might have missed an opportunity,” he says.

In the end, the uncertainty of the moment suggests communicators take these situations on a case-by-case basis, Dye-Anderson and Wang say. Variables that need to be considered, Wang says, include how egregious were the tweets/comments or activities; when did they take place; do they seem to be part of a larger pattern for the individual; what has the company done in previous instances like this; and has the person shown contrition and personal evolution.