One of the many great quotes I heard during last month’s PRNEWS Crisis and Measurement Summit in Miami was from luncheon keynoter Jim Lindheim, the former Burson-Marsteller chairman. He said that in the Tylenol scare days (1982), he used research to guide clients. Data helped him argue that what mattered wasn’t “what people were saying; it was what they believed.” That argument convinced Johnson & Johnson to take responsibility for its crisis and remove Tylenol from the shelves.

That incident has become the gold standard for crisis response. The sentiment rings true today, but in between then and now, social media arrived. And what people say now is much more likely to become what they believe. If they believe any medium at all, they’ll believe their “friends,” whether that’s a neighbor or an unknown follower on Twitter, who might well be a Moscow troll farm.

That credibility problem is very much what happened in two recent crises: The Houston Astros cheating scandal and the early days of the COVID-19 epidemic, where Chinese government officials suppressed information for weeks, essentially giving the virus a head start on its killing spree. Though Beijing fired several local Wuhan officials, it’s unclear whether or not central or regional government officials have blood on their hands. Perhaps both do.

No leader, corporate or government/nonprofit, welcomes bad news. They like talking about it even less. But if there’s one thing we’ve learned in studying crises during the last 20+ years, it is that the longer you wait to talk, the worse the crisis is going to get.

Today, things are somewhat different. Social media commentary and the steady drip of investigative stories fill the time between bad news breaking and an official spokesperson saying something.

Back when humans did most of the content analysis, I conducted a deep dive into the crises of all the clients we had, as well as those of their competitors.

I found when a crisis was addressed quickly and appropriately (e.g., the company promptly issued a credible apology, and indicated that it had taken action speedily), the crisis would be out of the headlines in one or two news cycles. Generally, there would be little long-term impact.

When companies failed to act quickly or appropriately, (e.g., blamed the customer, or did something else stupid when it came to handling the crisis), the negative coverage went on and on and on, and frequently became what we called a Reputation Killer.

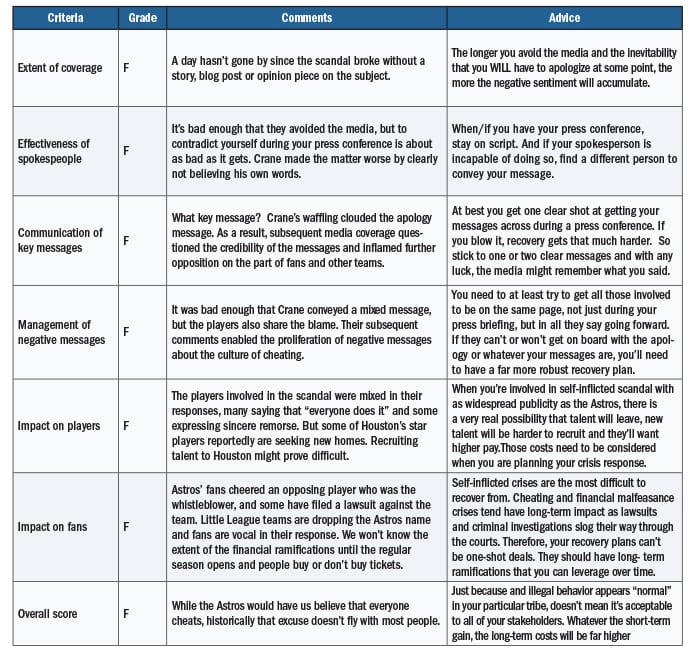

Houston Astros

Last year’s revelations that the Houston Astros set up cameras to monitor signals that the opposing team was using, and then banged trash cans to inform its batters what pitch was coming, might well be a Reputation Killer. Staying silent on the issue for months ensured that the franchise will forever be known as the team that cheated its way to a World Series win.

Perhaps if the Astros and Major League Baseball (MLB) addressed the problem sooner and more openly, Little League teams might not be ripping Astros off their team uniforms and fans wouldn’t be giving a hero’s welcome to a former Astros pitcher who decided to blow the whistle on the scandal.

When, in November 2019, “The Athletic” first published details of how the Astros stole pitching signals from opposing teams, the general public was shocked, but few baseball insiders were surprised. While the Astros denied the allegations and MLB investigated, both players and insiders admitted that while this particular form of thievery was unique, cheating wasn’t – hardly a response strategy designed to increase trust in the game.

Two months later, when MLB released its internal investigation of the Astros and confirmed that widespread cheating had occurred, it named just one player, Carlos Beltrán, now retired, in its findings. Apparently, this was due partly to players’ union protections. The result, though, was unsatisfying to baseball fans and opposing teams.

MLB’s January announcement of its internal findings made the public and opposing players feel as if baseball was attempting to obfuscate to keep the peace. Yes,MLB said , our internal investigation shows there was extensive cheating, but, no, we won’t say which players cheated. Story over. Let’s move on now. Perhaps MLB should have had an outside firm investigate.

The feeling that MLB was attempting to move on also manifested in the weak punishments. MLB fined Astros’ ownership a few million dollars and several draft picks were forfeited. Most important, though, the Astros were not forced to forfeit their World Series title, nor was ownership ordered to give up control of the team.

In response, the Astros finally acted. The team fired key staff members – the general manager and the field manager – as the report was announced. The team’s players, though, avoided the media and did not apologize. In addition, team ownership refused to admit guilt. MLB was tight-lipped, too. In fact, after issuing the findings of its report, MLB put a gag order on opposing teams commenting on the situation.

Non-Apology Apology

It wasn’t until a full month later, February 13, the start of Spring Training – three months after the scandal broke – that the team’s owners and player apologized. Sort of. The apology press conference was panned widely. It didn’t help that the team’s majority owner, Jim Crane, refused to take responsibility. Quoting Crane: “No, I don’t think I should be held accountable.” He also denied the cheating impacted games – only to contradict himself 55 seconds later. Incidentally it was Crane who fired the Astros’ manager and GM.

ESPN placed blame on Crane’s greed. “The Astros have widely been viewed as an organization where the bottom line is everything, which, in part, led to their recent scandals.”

As a result, fans and former players have filed numerous lawsuits. Most telling is the reaction of fans. Little League teams that had taken the Astros name are choosing new names. Fans are expressing outrage during spring training games. Opposing players, including superstars such as Mike Trout of the Angels, are lashing out at the Astros in the media. There’s no indication anywhere that the scandal is going to fade from the headlines anytime soon.

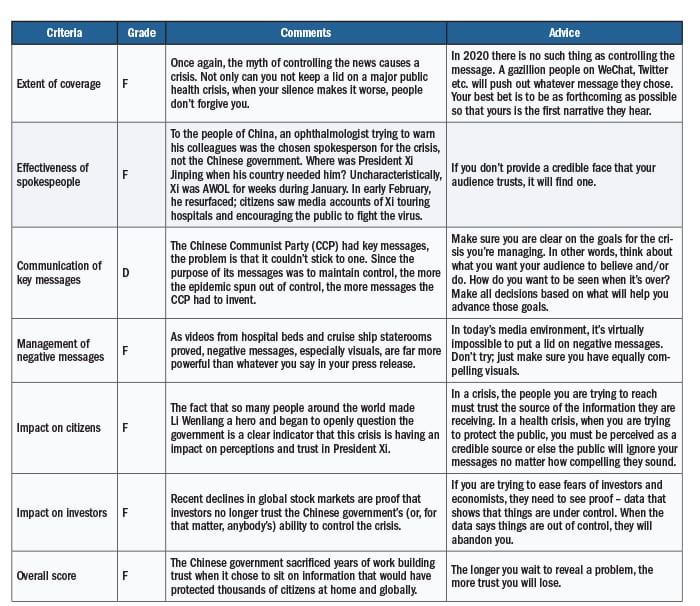

Beijing’s Response to COVID-19

In early December, health authorities reported a previously unknown form of pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Researchers now suspect that the virus may have begun spreading months earlier. But government officials, not wanting to disrupt plans for a giant community supper designed to break the Guinness Book of World Records for the most meals served, never mind the upcoming New Year celebrations, said nothing.

Between early December 2019 and Jan. 19, 2020, the message from Wuhan was that a few people connected to a local live market were infected with a new pneumonia-like virus. Whatever it was, it was not SARS, the virus that led to a global epidemic in 2003. Anyone who contradicted that narrative was silenced.

Throughout December, when measures might have been taken to limit the spread of the virus, rumors began circulating. Li Wenliang, 34, an ophthalmologist at Wuhan Central Hospital, noticed seven cases of a virus that looked like SARS. He sent a message on social media to his medical school classmates warning them.

Three days later police summoned him. He was accused of making false comments that had “severely disturbed the social order.” Dr. Li was ordered to stop spreading rumors. He went back to work, and ultimately caught the virus from a patient a few weeks later. He died Feb. 6.

His story was spread widely on social media and in the western press. In China, Li became a symbol of the frustration and mistrust that the citizenry harbor toward the central government over the virus.

Party Silences Alternative Messages

Meanwhile, the number of cases climbed as the Chinese Communist Party continued to control the narrative. Alternative voices were silenced quickly. Viruses, however, don’t recognize central, or even regional, authority. When the disease showed up in Hong Kong, the free (or, free-er) press in that city-state blew the whistle on the extent of the problem.

In the meantime, hundreds of thousands of Chinese people were exposed and quarantined. Many were herded into makeshift hospital facilities, whether they were sick or not. Global supply chains ground to a halt as workers were told to stay home, countries banned incoming flights from China and economic worries mounted.

The changing narratives from the Chinese authorities are calling into doubt the veracity of their reports, both at home and among health authorities and other governments around the world. Up until very recently, the economic prosperity that Chinese President Xi Jinping brought to his country ensured the autocratic leader’s continued popularity. The broad-ranging consequences of the government’s early missteps are causing an uncharacteristic backlash among Chinese citizens, who appear to have lost trust in the government’s ability to keep them safe.

CONTACT: [email protected]