There are few phrases that spill more often from the mouths of PR pros than corporate reputation. Moreover, plenty of articles, in this publication and others, extol the importance of corporate reputation. And how many surveys conclude that consumers prefer value-based brands? We’re told Millennials and Gen-Z especially will purchase from companies that support values such as DEI, sustainability, fair treatment of workers and human rights.

More than that, PR pros predicted 2022 will see brands facing consequences should they fail to stand behind their stated values.

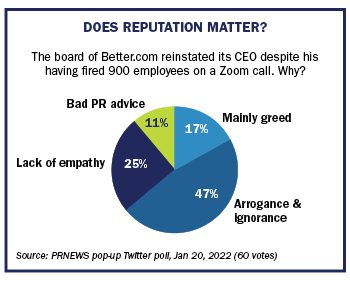

How, then, to understand why the board of Better.com, knowing its corporate reputation was ebbing, retained a CEO who coldly fired 900 staffers during a Zoom call in December and then trashed them online? (More on this below.)

And how to explain why value-based companies are risking their reputation and spending large sums as Olympics sponsors? For example, one of the newest partners, AirBnB, is paying the International Olympic Committee (IOC) $500 million through 2028. The Olympics Winter Games begin in Beijing, China, Feb. 4.

In fairness, many Olympics sponsorship agreements are long-term deals completed well before Washington announced an executive boycott of the Games Dec. 6, 2021.

Reputation vs. Values

But forget, for the moment, corporate reputation. Instead, look at something seemingly more solid, such as company values, which are found easily online.

For instance, in the Values section of its site, Coca-Cola, another Olympics sponsor, features a Human Rights policy. The English version runs nearly 4 pages.

Its first line is strong: “Respect for human rights is a fundamental value of The Coca-Cola Company.” It says later, “Our aim is to help increase the enjoyment of human rights within the communities in which we operate.”

Coke’s words, for the most part, are commendable. They’re also in line with those of many other companies that say they’re purpose-driven.

Views of Human Rights

However, based on media reports and previous experience, Beijing’s view of human rights seems wildly different from Coke’s.

For example, Coke’s policy says, “We strive to create workplaces in which open and honest communications among all employees are valued and respected.” The same can’t be said about China’s government. A recent media report detailed how the government rounded-up Chinese free speech advocates as the Games neared.

And then there’s the sticky issue of media access for the Beijing games. In its contract with the IOC, Beijing promised media would have full access during the Games. Based on journalists’ experiences during the 2008 Olympics in China and recent events, the Committee to Protect Journalists isn’t hopeful.

An Ignominious Distinction

For the third year in a row, China in 2021 was the world’s leader in jailing journalists. Moreover, 2021 saw media access for global journalists in China decline “significantly,” per the Foreign Correspondents Club of China.

And China has warned that punishment awaits visiting athletes who say things during the Games that are not “in the spirit of the Olympics.”

As far as free speech online goes, some countries are urging their athletes to bring burner phones to the Games. And they’re telling them it’s likely Chinese authorities will track their online conversations, despite promises that China’s so-called Great Firewall of online censorship and monitoring will cease during the Games. Athletes are urged to discard the burners prior to returning home.

So, purely on the face of it, sponsoring the IOC contravenes companies’ stated values. In addition to facing the barbs of human rights groups, the White House and US lawmakers, reports have Beijing pressuring brands to support it against boycott calls.

And Beijing’s not an easy partner. The NBA learned this in 2019 and 2020. Fallout from the league’s China foray continues in 2022. Walmart and Intel are only the latest companies in hot water with Beijing.

The Olympics' Marketing Promise

Despite mounting criticism, obvious contradictions with corporate values and the possibility of reputation damage, Olympics sponsorships remain valuable for some companies.

On the other hand, corporate tactics have changed compared with previous Games.

For example, some are in a quandary. Mike Paul, president & CEO of The Reputation Doctor, says, “I got a lot of phone calls” from companies when Washington announced its boycott.

And several companies are remaining silent about their sponsorship deals or downplaying their participation, says Arthur Solomon, a veteran sports PR pro and former SVP/senior counselor at Burson-Marsteller. Adds Katie Paine, CEO, Paine Publishing, “brands are ducking for cover and PR people are just hoping they don’t get a 3 am crisis call.”

Instead of running splashy, new content for the Games, they’re opting for legacy ads. Some, says Reputation Partners’ EVP & GM Andrew Moyer, are emphasizing that they’re “supporting athletes, not the Games.” Another route companies are taking, Moyer says, is downplaying messaging for the Games intended for US audiences, but going full-tilt with messages for the China market.

Does Reputation Matter?

For Solomon, reputation itself is part of the issue. Reputation, he says, is a “PR-invented concept…it’s overrated and overblown…and it takes a back seat” to glamor partnerships like the Olympics.

In addition, companies that make good products or offer services in great demand don’t need to worry as much about reputation, he says. “The bottom line is that when consumers need, want or enjoy a product, the reputation of a company means little.”

Moyer adds more nuance about reputation’s seeming lack of importance. “Reputation has a shorter lifespan than many other things in the consumer’s mind,” he says. In addition, reputation often is seen as more important to employees than to consumers.

The Exceptions

Still, Moyer and Paul largely disagree with Solomon’s view of reputation. In cases where a company has a near-monopoly, like Boeing and Facebook, its reputation can tank and have little effect on revenue and success, they say. Yet, “those companies are the exception,” Paul says.

For Paul, corporations decide about joining a controversial partnership based on a risk assessment. “You partner with the Olympics based on how much money you believe it will mean for your company versus the obvious hits your reputation could take,” he says.

Companies at the Olympics “have determined they might take a reputation hit, but the awareness and revenue the Games could generate trump reputation and brand.”

A Deep Dive

An assessment of either an event or a person, Paul says, should “peel back a lot of onions” with questions like, ‘What are our competitors doing?’ ‘Will an event that (or person who) made money previously do so now?’ “If you think you have a quick answer” on joining a glamor project or making a controversial decision, “you’re wrong.”

For the 2022 Olympics, Paul says, the assessment is a bit different in that social media, Chinese censorship aside, allows “any athlete or fan” to create controversial content. On top of that, Covid issues, such as sponsoring an unvaccinated athlete or a Covid breakout during the Games, must be considered, he adds.

Paul emphasizes companies need to “ask worst-case questions” during the risk assessment. “Don’t assume everything will be alright.”

For example, the Australian Open, on its face, seems a benign event. Yet companies working with Novak Djokovic found themselves in hot water. “People who weren’t even tennis fans were aware” of the PR crisis with Djokovic and China’s Peng Shuai, he says.

The lesson is clear, he says. When a risk assessment leads a company to participate in a possibly risky event such as the Olympics, it must prepare “responses to the top 20 questions” you’re likely to be asked if an incident occurs.

Better.com and Reputation

Risk assessment also explains why Better.com’s board kept Vishal Garg as CEO, Paine says. In this case, Garg’s money-making history, specifically a $750 million cash injection, outweighed reputation hits, she says. “If he was losing money and hadn’t gotten those investments, he’d be gone for good,” Paine says. Paul agrees, but warns a person’s or event’s history of making money “can blind” companies.

Paine admits risk assessments are not standardized exercises. Who participates and their viewpoints color the outcome.

For example, “Marketing and Legal…see everything through a revenue funnel. Communication, by necessity and charter, takes a much broader and longer-term view of company success. Communicators," she says, “think in terms of culture, investors, customers, partners and employees.”

CEO Reputation

Solomon downplays the importance of CEO reputation as a concept. "The CEO’s reputation is not a major concern of companies or Wall St.,” he says. Most important is how the CEO runs the company, “meaning how much money the company makes.”

The reputation of a CEO, he adds, comes into play only when there are criminal charges against a leader. “Or when the company or its CEO are shown to be untruthful or there’s constant negative media coverage of a problem.”