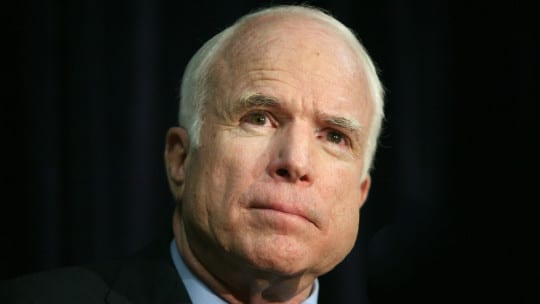

It was April 2013. Senator John McCain had just participated in a National Geographic Channel event in Washington, D.C., to publicize an episode of “Locked Up Abroad.” In the episode, McCain and Ernie Brace, a civilian who’d flown spy missions over Vietnam for the C.I.A. and was shot down, recounted being jailed in solitary confinement for years, never meeting during that time, but keeping each other sane by tapping messages and jokes via Morse code to each other on the shared wall of their cells in the infamous Hanoi Hilton.

Brace said he owed his life to McCain; the senator deflected the compliment. McCain insisted it was Brace who prevented him from going crazy. The two laughed and teared up that evening, some 40 years later. Brace spent seven years in Vietnamese prisons, McCain nearly five. "It was terrible," Brace said. Neither he nor McCain wanted to go much deeper than that.

Their first face-to-face was in May 1973, at a White House dinner President Richard Nixon hosted for former POWs. McCain thought he'd located Brace when he looked into a sea of military uniforms and found one honoree in a suit. He was correct.

Press Protocol

Alone in the parking lot with McCain after the National Geographic event, I approached with trepidation. It was an emotional night for McCain and I was sure he was glad to be leaving. The last thing he needed was a media question. I identified myself as a reporter and asked if he could forgive Vietnam for his incarceration.

"I have nothing against the Vietnamese people...they're good people...it's a nice country...I've visited [since the War] and liked the country...I was glad when President Clinton normalized relations with Vietnam." True, he said he'd rather not meet his captors again, but the former prisoner harbored no ill will toward the Vietnamese people.

The response was impressive and shocking. A bit later I realized it was either a well-rehearsed answer from a public figure who knew how to handle himself in front of the press no matter the circumstances or this was a person with an extraordinary ability to forgive. I realize now it was both.

Though he despised some of what the media said about him, McCain believed a strong press is critical to democracy’s survival, so he respected the media and made sure his staff did, too.

From The Top

Another lesson: culture begins at the top of an organization. As such, reporters knew McCain’s staff, including his highly respected special defense assistant Anthony Cordesman, to be among the most responsive on Capitol Hill. The media, in turn, gave McCain a fair shake most of the time.

McCain's policy of access to the press is perhaps why the media blew up when President Trump insulted McCain's war record. During that terrible time McCain was able to stand above the fray; his solid relationship with the press was doing the work of defending him. Certainly there’s a lesson or two there for communicators and crisis management.

“Senator McCain’s relationship with the press was built on a framework of respect that grew from a lifetime of defending the First Amendment,” says Anthony DeAngelo, director for media relations at APCO Worldwide and a former Capitol Hill staffer. He adds, “His approach was open and honest. It should serve as a model for public servants and public figures when working with the media.”

Indeed, during McCain's unsuccessful presidential campaign he refused to be handled and instead sat in the back of his campaign plane so he could chat with reporters.

McCain’s ability to forgive and then work with the opposition to solve problems also offers a lesson or two for brands and communicators. Fellow Arizonan and Republican Senator Jeff Flake said as much yesterday; so did John Kerry. “He would quickly forgive and move on," Flake said, "and...see the good in his opponents, that is something…particularly these days we could use a lot more of.”

Seth Arenstein is editor of PR News. Follow him: @skarenstein