Machiavelli would have loved both the Experience Regina promotional campaign and the most recent Bud Light influencer program.

Presumably, the goal behind promotional efforts by Regina Exhibition Association Limited (REAL), the tourism board of Regina, Canada, is to attract tourists. And we assume that its target audience would be people who don’t live in Regina.

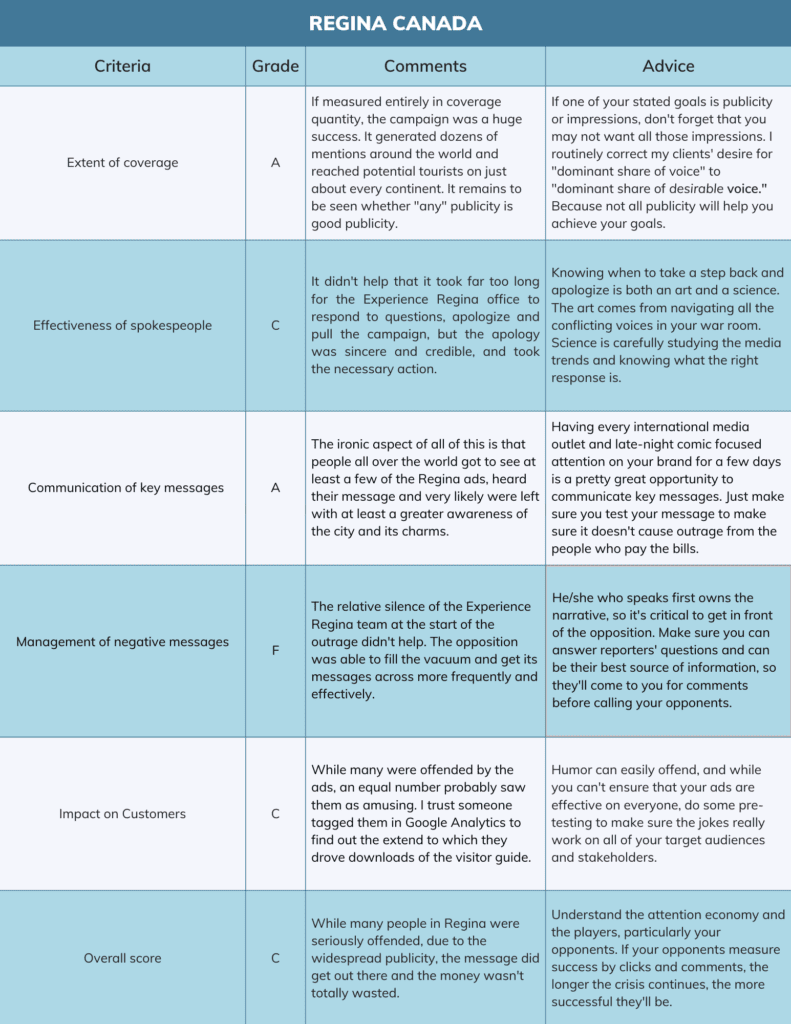

Based on those assumptions, it’s reasonable to deduce that the recently launched “Experience Regina” campaign was a smashing success. It received a ton of publicity and made headlines around the world, reaching millions of potential tourists with enticing pictures of their Saskatchewan city, but for all the wrong reasons. The campaign played off an old joke on the pronunciation of the city’s name, which happens to rhyme with certain lady parts.

And while potential tourists might have loved it, the local citizenry (who presumably paid for the campaign with their tax dollars) did not. Local businesses and officials were outraged, calling the campaign sexist and demeaning. As a result it was quickly pulled, despite the fact that the campaign had completely succeeded in its goals, although we’ll probably never know how many people actually made vacation plans as a result of the ad.

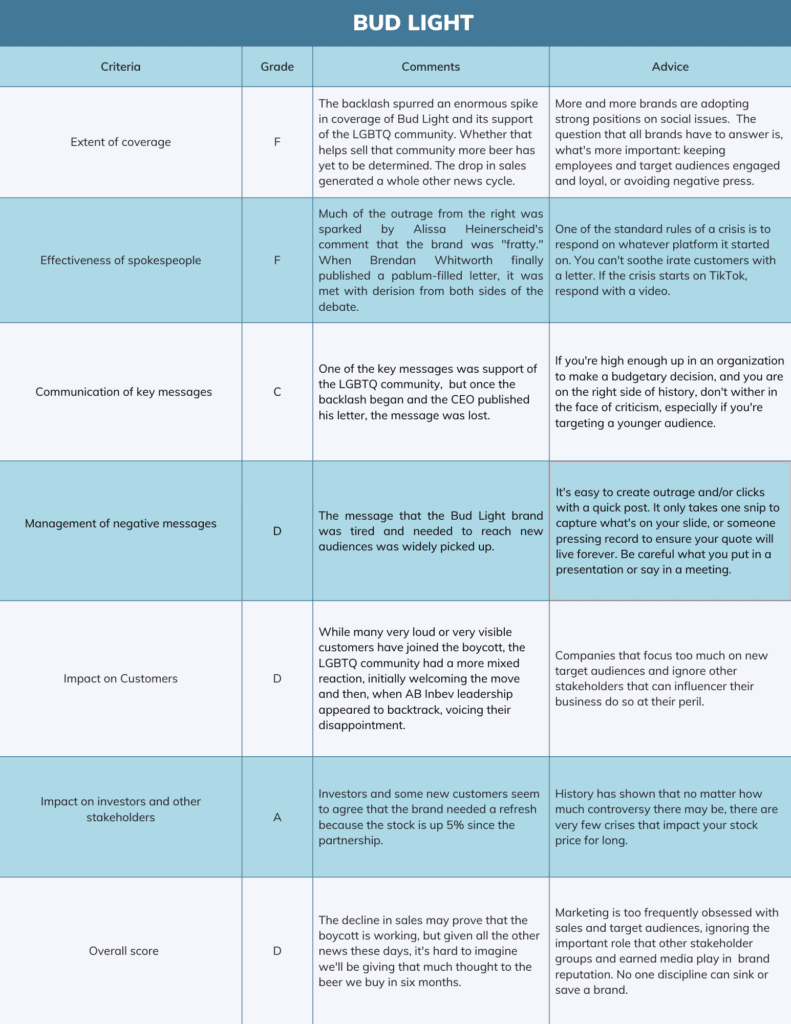

Bud Light, meanwhile, sparked a larger brand crisis when, as part of a brand refresh, it sent some of its famous blue cans to trans TikTok star Dylan Mulvaney to celebrate her first year after transition. After years of declining sales, Bud Light’s Vice President of Marketing Alissa Heinerscheid explained her job was to "evolve" and "elevate” the brand and lose its “fratty” reputation.

The goal of the Mulvaney paid influencer campaign was to reach a younger, more diverse audience, which it certainly did, given Mulvaney’s millions of followers on social media.

Just like Experience Regina, the campaign initially succeeded in all of its stated goals. It generated a ton of publicity and good will among its new younger target demographic and especially among the trans community.

And just like in Regina, the beer brand forgot about a very important constituency: the existing customer base, many of whom bought into much of the anti-trans rhetoric that is rampant on right wing social media and news outlets.

Conservative Kid Rock responded with a video showing him using the beer for target practice and right-wing pundits called for boycotts of the beer, politicians refused to drink it and even tried to fundraise off the outrage.

Investors shrugged off the noise, and shares in AB InBev went up. Sales of Bud Light, however, dropped precipitously. And while there are many other potential explanations for declining sales, the conservative media is taking full credit.

Personally, I thought the Regina ads were brilliant because they made me want to actually go there and check out the city. And while I’m no more likely to drink Bud Light today than before its controversy (I’m an IPA-only beer drinker), when I saw Mulvaney’s post my reaction was that sending her cans of beer on her anniversary was a smart thing to do.

The Impact of Today’s Political Landscape

When I moved into marketing from years as a journalist, I was taught that achieving the stated goals and objectives defined success. As long as you reached the right audience with the right persuasion messages and tactics, you earned your keep.

But that was in the before times, before social media, before attention became the purpose, and outrage, feigned or real, was part of the process.

In 2018, Nike was one of the first to actually court that outrage with its controversial Colin Kaepernick ad—and sold a lot more sneakers. We don’t know yet whether Regina will attract more tourists, but we do know that sales of Bud Light are down since the Mulvaney controversy broke. That may be correlation not causation, but the drop in sales drove another whole news cycle by conservatives claiming victory.

In an era when a mere knock on the door or a strange car in your driveway can be met with gunfire, no one should be surprised at negative backlash to a marketing campaign.

Many have suggested that these brands didn’t do their research, but I’m not sure either crisis could have been prevented by better research into the likely response of the target audience, because in neither case did the target audience drive the backlash. And market testing wouldn’t have helped either because who would bother conducting an expensive testing program on people outside the target audience? And, again, both campaigns succeeded at their stated goals.

What went wrong was that both campaigns focused too much on “target audiences” and not on their stakeholders—those “others” that control their fate.

They also overlooked the landscape they were operating in.

What caused the size of the uproar in both cases was that for many people, politicians, media outlets and pundits, the measure of success is attention, which is measured in clicks, likes, comments and eyeballs. And nothing is more controversial and attention-getting than sex.

Katie Paine is founder and CEO of Paine Publishing