Oct. 19, 2011—9 a.m., Atlantic Standard Time: It is a typical workday morning at Canaport LNG, a state-of-the-art liquefied natural gas receiving and regasification terminal in Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada.

Typical until management is alerted to a fire at a petroleum company that borders Canaport’s property. As the first liquified natural gas terminal of its kind in Canada, fire is not Canaport’s friend, given that the facility has a maximum send-out capacity of 1.2 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day. Hearing the news from Canaport’s incident manager, Kate Shannon, the company’s media relations director, moves to the Emergency Operations Center—one of Canaport’s large conference rooms. In the room are Canaport’s management team, including Fraser Forsythe, director of operations and incident manager during crises. It will be critical that Shannon and Forsythe work together for a successful conclusion to the crisis. “I have to coordinate operations and make the calls to emergency services, but it’s important to integrate those actions with communications,” says Forsythe.

9:30 a.m.: After soaking up as much information as possible within the emergency operations center, Shannon meets her goal of issuing a press release within a half hour of the first call. Targeting the local press, partners and stakeholders (including local government officials), the release covers the basic facts: There is a fire from a neighboring property that could threaten the Canaport facility; all emergency steps are in place, including calls to police, fire and ambulance personnel.

9:35 a.m.: While it is in a remote location, Canaport LNG does have seven families residing in the area. Shannon calls each of them to give an update.

9:45 a.m.: Much to the team’s dismay, the fire is spreading—getting closer to crossing into Canaport LNG’s boundaries and near its tanks and lines. Shannon starts revising the first release to reflect the update.

Shannon checks with her communications response team of three, set up in one corner of the emergency operations center, which helps take calls while monitoring Twitter and Facebook chatter.

10 a.m.: A member of the local media shows up at Canaport LNG’s main gate, confronting security and insisting on access to shoot video of the fire. Shannon takes a quick drive to the location, and directs the media crew to the best possible vantage point—without breaching the facility’s tight security perimeter. The updated news release goes out.

10:30 a.m.: Back at the operations center, the calls are coming fast and furious. One of them is from a neighbor. They don’t have a car, and are worried if they have to evacuate. Shannon lets them know that if that time comes, they will have transportation away from the terminal.

10:45 a.m.: A father calls, frustrated in his ability to contact his daughter, who works at the plant. Shannon works to get them connected.

11 a.m.: The fire department is now getting the upper hand on the blaze, which Shannon is happy to report in her next briefing.

11:30 a.m.: The entire Canaport team listens to a local TV news special report of the fire. The station’s information is on the mark.

12 noon: The fire is close to being completely out—all that is left is scorched earth that has come a bit too close to the Canaport facility.

For Shannon, it’s been a good day. Performing under pressure and discovering strengths and weaknesses is a positive thing, she says. And, she’ll be more prepared than ever for the “real thing.”

|

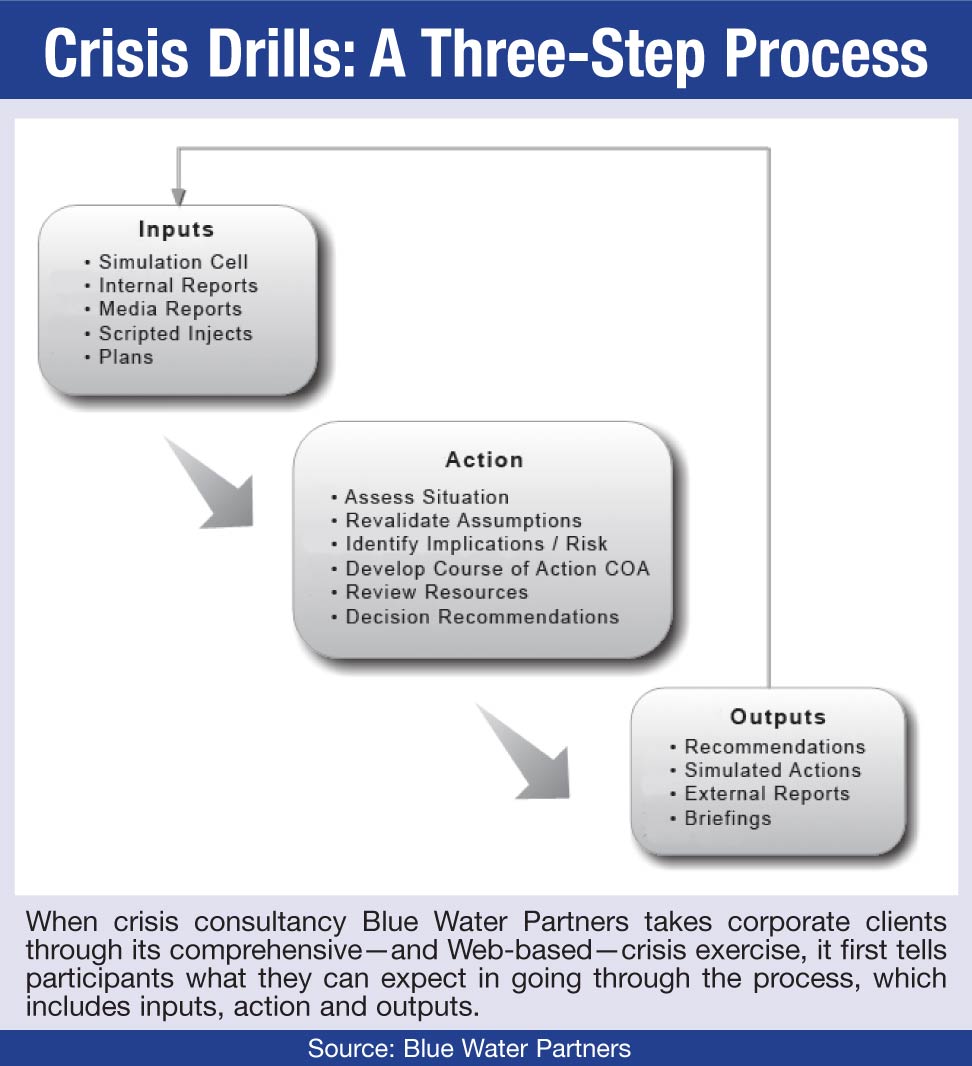

For this was a crisis drill, engineered via an online application created by Blue Water Partners, a company that creates and executes “corporate war games.” The application is designed to be as real as a drill can get and involve as many staff, partners and key stakeholders as needed. Burton says up to 90 people have participated in a Blue Water drill—from locations worldwide.

And “war games” is apropos, considering the experience of Rob Burton, Blue Water’s director of risk management and the person who creates the games. Burton has served as a crisis management consultant in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and before that was in the U.K. Special Forces, where he admits that military drills featured bullets whizzing by participants. Organizations’ crisis plans need to be tested under fire, says Burton—though not in the literal sense. “Crisis plans are living documents,” he says. “They need to be built into an organization’s system, and they must be tested regularly.”

There are some challenges unique to PR when it comes to these drills, says David Kalson, CEO of Ricochet PR, which has partnered with Blue Water to handle the PR aspects of the drills.

One of the biggest PR hurdles? “Just to be in the room,” says Kalson. “PR during a crisis is still treated as an afterthought.” On top of that, many organizations still don’t have crisis plans at all from which to draw from.

For Shannon, the Oct. 19 drill was an improvement on one deployed a year before. Information was flowing more freely from other sources, like HR and communications, she says.

And while Blue Water provides realistic “injects” that take a crisis to the next levels—including simulated TV broadcasts, social media posts, and even live “actors” breaching security fences—Shannon says it’s tough for communicators to fully realize the intensity of emergency situations. That’s why she feels strongly about PR’s involvement in the planning of crisis exercises. “It’s important that we plan realistic communications issues or situations that may arise,” she says.

As for the results of Canaport’s drill, Forsythe has just received an initial report on the October drill created by two outside firms. A more formal, final report comes later, which gets shared with government agencies.

Besides making an organization more crisis-ready, Burton sees another value of these drills: “Simply bringing people within an organization together who may not have much contact otherwise is very beneficial,” he says. Now that situation is a crisis in and of itself. PRN

CONTACT:

Kate Shannon, [email protected]; Fraser Forsythe, [email protected]; Rob Burton, [email protected]; David Kalson, [email protected].