Reporter Kashmir Hill of the NY Times likens the internet to “a fossil machine.” It preserves our reactions, photos, jokes, songs, political positions, foibles and much else “in silicon amber, just waiting to be dug up.” Social content that describes who you were years ago is flattened, fossil-like, into who you are now, Hill writes.

Digging up those fossils is bloodsport now. It consists of finding old material on social that will embarrass a target, putting it on display “for all to see and hop[ing] for the worst.”

Particularly vulnerable are the young, who grew up chronicling much of their lives on social. As a result, they provide a lot of material for social media archaeologists. Recently, fossilized posts of two young journalist were discovered. The results were just as Hill described.

First there was Alexi McCammond, 27, whose disparaging tweets about Asian-Americans, posted 10 years ago while she was in college, resurfaced. The controversy over those tweets led McCammond and future employer Condé Nast to agree that she should vacate the top editorial job at Teen Vogue just days before she was set to start.

The controversy erupted when editorial staff objected to McCammond leading the magazine in light of her past tweets and in the midst of hate speech and violence erupting against Asian Americans.

Another Young Journalist Hit

Now there’s Emily Wilder, 22, a recent Stanford University grad, ousted May 26, after just two weeks as an editorial associate at the Associated Press (AP) in Phoenix, AZ.

In Wilder’s case, her precise offense is unclear. While at college, Wilder, who’s Jewish, tweeted about her opposition to Israeli policies. In addition, she was active in college groups that advocated for Palestinian rights.

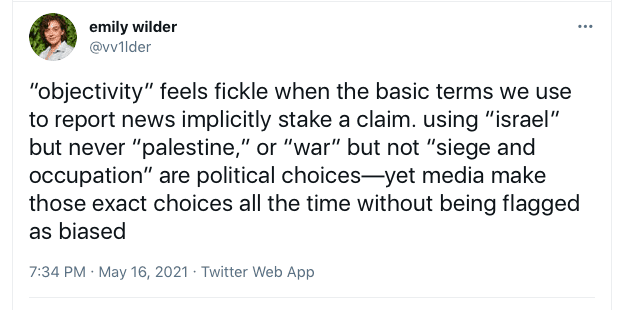

During her AP stint, which was described as a non-reporting job, Wilder re-tweeted articles about the death toll from recent fighting between Israel and Hamas. In addition to other posts, she tweeted an observation about the implications of journalists’ language choices [see tweet]

Back to School

On May 24, Stanford’s College Republicans unearthed Wilder’s college tweets. In a series of social posts, the group branded her “an anti-Israel agitator.” The thread caught the internet’s attention, as well as the AP’s.

An AP editor phoned Wilder May 25 to say her college tweets were not fatal. Wilder says the editor told her AP would support her as she took fire online from the Stanford group and others.

Wilder says she also removed “#BLM” from her Twitter profile, per a suggestion from the editor.

The next day, though, Fox News and other conservative outlets highlighted Wilder and her tweets, intensifying the situation. The same editor called Wilder to say she was fired.

Her dismissal letter, which Wilder shared with BuzzFeed News, notes during her first week on the job she met with an editor “about the social media expectations of AP journalists.”

In addition, the letter says Wilder’s college posts “prompted a review of your social media activity since you began with the AP.” That review “found...some tweets violated AP’s News Values and Principles.”

Which Post(s) offended?

But which post(s) ran afoul of AP’s policies? Eschewing transparency, AP has not specified the offending posts. Wilder asked, but received no answer. When reporters covering the story inquired, AP said only that Wilder was fired for something she posted while on the job, not her college posts.

“Why not say which one it was? It feels like a puzzle with one piece missing,” says Inspire PR Group founder Hinda Mitchell.

It’s more than an academic argument. Mitchell believes that, without specifics, “we really don’t know why she was fired...it leaves you guessing...were they buckling to conservative critics? Her reporting wasn’t going to be biased. She didn’t cover international affairs.”

AP’s lack of transparency goes against a basic rule of crisis, she says: ‘Create a narrative so the public isn’t left guessing.’ When there’s no official narrative, others will create one for you, and you may not like it.

Mitchell is not alone. More than 100 AP reporters signed an open letter blasting the organization on several fronts, including its lack of transparency.

For example, the letter seeks “clarity about the disciplinary process used for Wilder, including which social media posts warranted termination and why...it remains unclear—to Wilder herself as well as staff at large—how she violated the social media policy while employed by the AP.”

It also implies Wilder was ousted in response to a “smear campaign...interest groups are celebrating their victory and turning their sights on more AP journalists,” the letter adds.

Besides demanding clarity about Wilder’s ouster, the letter urges that:

- the AP clarify what “best social media practices” are;

- the company convene a “diverse” group to update social media policy so it supports “evidence-based, nuanced social posting;” and

- it produce “a clear commitment to, and play book for, supporting staff targeted by harassment campaigns.”

More Transparency, Sort of

Four days after the May 26 firing, AP managing editor Brian Carovillano added detail, though it seemed weak gruel.

He told CNN’s Brian Stelter that Wilder’s transgression was “a series of social media posts that showed a clear bias toward one side and against another in one of the most divisive and difficult stories we cover.”

Carovillano confirmed again that her offenses were committed while she was on AP’s payroll, perhaps shielding the organization from comparisons with the McCammond affair, where college tweets were the main issue.

Wilder’s firing, he told Stelter, was a “difficult…[but] unanimous” decision that AP editors reached.

Carovillano also linked Wilder’s posts with the safety of AP staff in war zones.

“Journalists’ safety is at stake…our social media guidelines exist to protect [AP’s] credibility, because protecting our credibility is the same as protecting journalists.”

Mitchell wonders if warring factions are concerned “with the social posts of a 22-year-old in Phoenix...that’s a stretch.”

So, as we do each month, we ask if a crisis was averted, acknowledging we’re using the term ‘crisis’ loosely.

Mitchell considers it an incident not a crisis, though she’s unsure it’s over.

“Wilder has said she’ll be back, though I can’t see her bringing a lawsuit [over her firing]. She wasn’t there long enough and so was probably still on probation.”

Post-AP, The Washington Post?

It’s possible the incident will touch another media outlet. One of the AP editors who allegedly concurred on the Wilder firing was Sally Buzbee. The veteran AP journalist and editor was named top editor at the Washington Post, replacing the retired Marty Baron.

The first woman to hold the job, Buzbee began at the Post June 1. Some speculated her arrival could prompt staff protests, similar to those that led to McCammond’s decision to exit Teen Vogue. At our press time, all was quiet.

That said, Mitchell sees internal blowback at AP as the biggest issue. She expects it will hurt morale and damage recruiting and reputation among journalists, though not the public, “which is not obsessed with journalism.”

Still, she believes AP must prepare for lingering questions from staff and recruits. And it should implement a transparent social media policy. “This seemingly small action really is only just starting to play out,” she predicts.

A better route, she says, might have been using the moment as a teaching example, instead of firing Wilder.

Mitchell also sees a time in the future when such incidents will be so common they’ll be non-starters. Everyone applying for a job will have something in their social media past they’ll want to avoid discussing, Mitchell says, including people in HR doing the interviewing.

Perhaps. Hill offers 2 scenarios.

In 2010, data scientist Jeff Jonas envisioned people becoming more tolerant knowing that data about their lives was on display and that everyone potentially was vulnerable. In a way, Jonas predicted the opposite of cancel culture.

That same year, then-Google chair Eric Schmidt saw a different route for young people grappling with indiscretions on social media.

Upon reaching adulthood, Schmidt predicted, young people would change their names as a way of escaping youthful mistakes contained in their digital histories.