“Kings are the slaves of history.”

—Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

In today’s personality-driven culture, it’s sometimes hard to sort out whether it’s the guy at the top who causes a crisis or the culture he has created within the organization. Either way, most of the time, a crisis starts at the top. But in 2017, one could make the case that cultural and social norms are exerting a greater influence than the people in charge. The crises we’ll examine here, we would argue, owe as much if not more to changing norms than to corporate leadership.

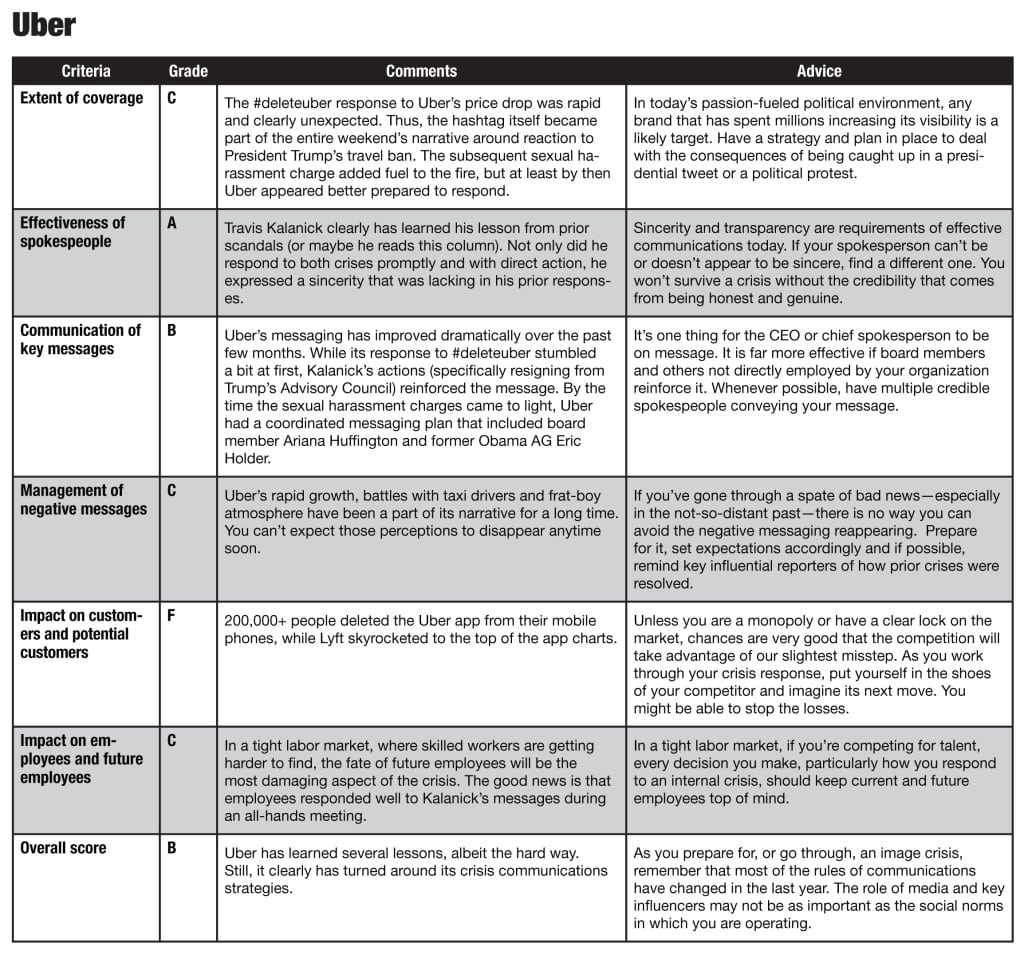

Uber’s most recent crises are in many ways products of the social issues roiling our society. When taxi drivers called a strike in support of immigrants, Uber lowered its prices in NYC. The perception was that Uber was trying to profit off the striking workers. In response the #deleteuber hashtag trended on Twitter and more than 200,000 people deleted the app. Many switched to arch-rival Lyft, whose CEO pledged to donate $1 million to the ACLU.

Just a few weeks later another crisis erupted. A former employee, Susan Fowler, posted a blog detailing the sexual harassment and sexism she experienced at the company. Those charges played into two social narratives that have been top of mind in the last year. The first was sexism in the tech industry, which first came to the fore in 2015, when Ellen Pao sued her former employer, venture capital darling Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, for sexual discrimination. Little has changed since she lost the suit. In 2016, sexual harassment dominated headlines with the lawsuit against Bill Cosby as well as the infamous Access Hollywood video of then-candidate Donald Trump. Fowler’s charges fueled existing perceptions of Uber and Silicon Valley tech culture.

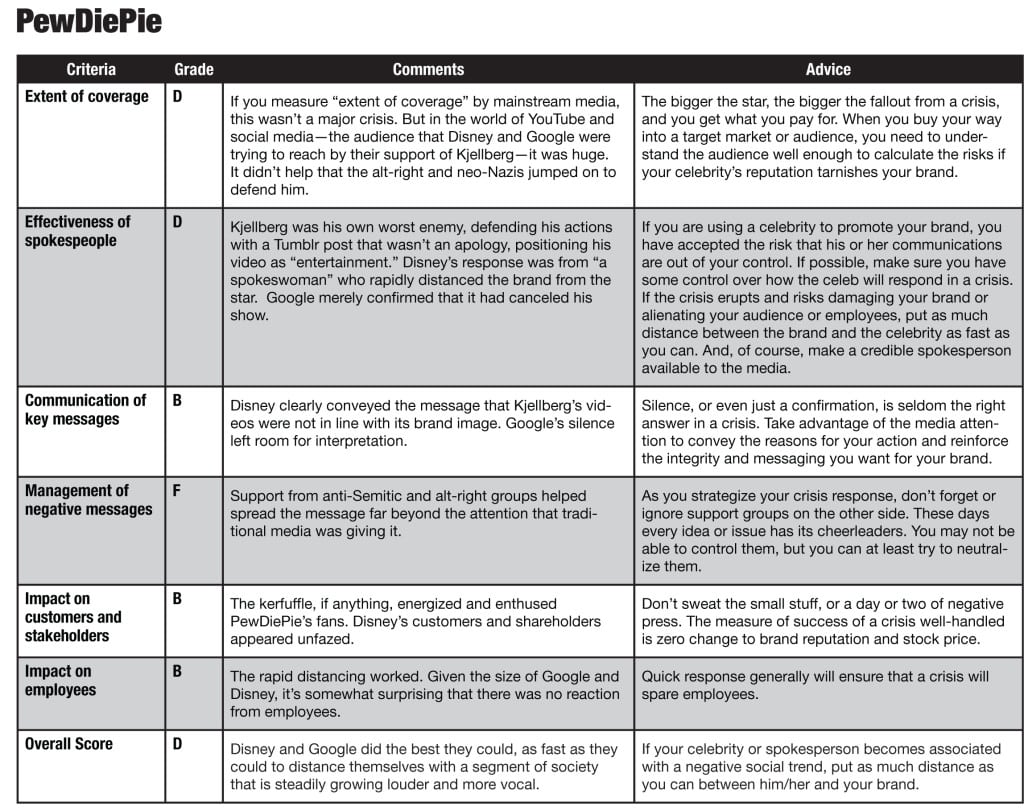

Similarly, the crisis surrounding YouTube’s biggest star, PewDiePie ( aka Felix Arvid Ulf Kjellberg), played into concerns about the rise of anti-Semitism and the alt-right movement. When the Wall Street Journal reported on the anti-Semitic language featured in Kjellberg’s videos, Disney’s Maker Studios quickly severed its contract with him. YouTube followed suit by canceling his show; Google dropped him from its lucrative Google Preferred advertising program. Little surprise here. The videos were typical of the Swedish YouTube star: laden with expletives and the kind of humor that appeals to his 52 million mostly young male viewers. Only this time, neo-Nazi groups crowed and critics worried that the videos normalized Nazism, a top-of-mind issue globally. As such, brands couldn’t get far enough away from PewDiePie fast enough.

While these crises were sufficiently heinous to cause a media storm, we postulate the media environment and changing cultural awareness both exacerbated the crises and shaped the responses. In the past, brands could operate in a bubble: All that mattered were customers and target audiences, and they cheerfully could ignore political upheaval. Things have changed. It’s time to rethink the role that media, influencers and people in the streets will play and plan accordingly.

CONTACT: [email protected]