Before sending gifts became ethically questionable, sometimes I would send crisis-survival kits to people I worked with when a crisis blindsided them. Typically, the ‘kits’ included cookies, an alcoholic beverage of choice and a stress-relief toy that they could crush, throw or punch. It was our way of saying, ‘We feel your pain and know you’re working late and over the weekend because someone somewhere did something stupid that involved your brand.’

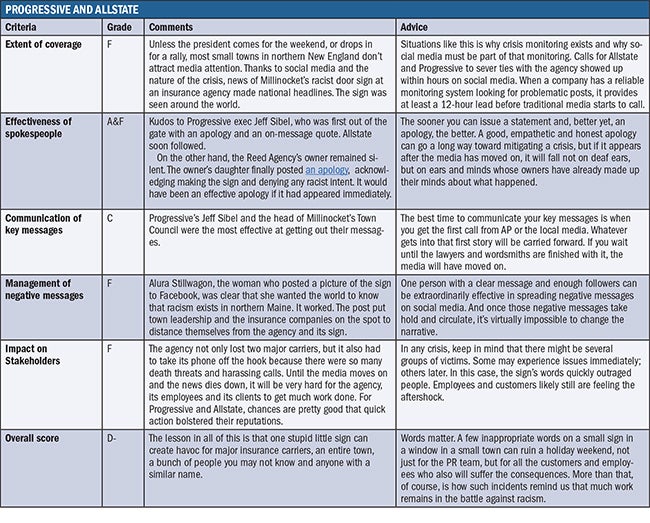

I would have sent such packages to the folks at Progressive and Allstate last month after one of their locals posted a dumb, racist sign on its door, announcing the agency was closed for the Juneteenth federal holiday.

And, as happens these days, even though the agency served a small town in northern Maine, within hours the sign, and reactions to it, were all over social media.

So, it’s certain the Crisis/PR teams at both companies spent at least part of their holiday weekend holed up in a war room somewhere, crafting a response.

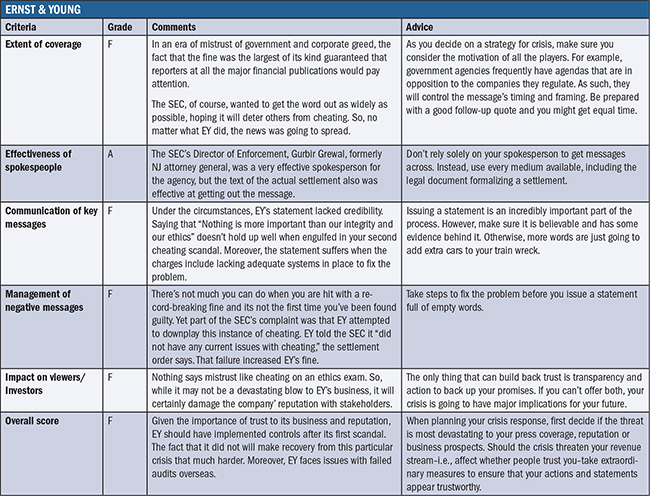

And, while PR folks at Ernst & Young Global Limited (EY) probably had more time to prepare, they likely were locked in a similar room, crafting a response to an SEC announcement about its largest fine against an auditing firm. The Commission discovered that some EY auditors cheated on…wait for it…the ethics portion of their exams to become certified public accountants (CPA).

In both cases, the actions behind the crises had people wondering: What were they thinking?

In one case, though, fast action protected the brand and helped make the issue go away. In the other, the crisis is at the very core of the business. Implications for the brand are much longer lasting.

Progressive and Allstate

Progressive and Allstate spend a ton of money promoting their brands–on TV, in sports stadiums and pretty much anywhere you can imagine. As a result, the public’s perception of the brands is high.

Accordingly, people reacted quickly when the Harry E. Reed Agency in Millinocket, Maine, (population: 4,000) chose to let customers know it was closed for the Juneteenth federal holiday with a racist sign in its door. A fellow resident walked by the agency’s door, snapped a photo of the sign, and posted it to Facebook, commenting, “The racism in Millinocket is real.”

Not surprisingly the post quickly spread and thousands of people shared it. And it didn’t take long for some of those people to post the names of insurance brands that Reed represented.

Within hours some of those thousands who shared the post began leaving one-star reviews of the agency on Google and Yelp. In addition, they demanded Progressive and Allstate stop doing business with the Reed Agency.

Within 24 hours Progressive had severed ties with Reed and issued a statement. “Diversity and Equity and Inclusion are fundamental to our core values,” Progressive’s statement read. As such, the sign was in violation of Progressive’s commitment, so it terminated its relationship with Reed’s agency.

Allstate followed suit within hours, also terminating its contract with Reed, hoping this would quiet or end the controversy.

Probably the longest impact will be on the poor PR person in Millinocket tasked with trying to get tourists to visit the central Maine town.

The town council’s head condemned the sign, calling it a “blatant disregard of human decency.” He went on to say “It is deeply saddening, disgraceful and unacceptable for any person to attempt to make light of Juneteenth and what it represents for millions of slaves and their living descendants.”

But a simple search of news about Millinocket will tell you that it might be a while before the town and racism don’t show up linked in the top ten results. It’s even spread to other insurance agencies with similar names.

Ernst & Young

Instead of one rogue agent as in the previous example, EY’s crisis included hundreds of auditors sharing an answer key to an ethics exam for several years, from 2017 to 2021. The irony is inescapable. A firm whose very existence depends on trust, creates a culture in which its auditors–the people actually looking at your data–aren’t trustworthy.

It would be one thing if the ethics portion of the exam was grueling and required extensive preparation and studying. But, according to a CPA course review site, that’s not the case at all. It’s “an open-book, multiple-choice test that covers essential accounting ethics concepts. The exam is more like a self-study, open-book test. You will have plenty of time to take the test and answer all of the questions.”

It would be easy to blame it on the stupidity and lack of integrity among the 49 auditors who cheated on an easy part of the exam. But, EY’s reputation on cheating is spotty and seems a cultural flaw.

For example, this isn’t the first time that EY employees were caught cheating. From 2012 to 2015, more than 200 employees tampered with testing software, rigging scores on continuing-education exams, the SEC settlement order says. And two years later, there was another cheating episode.

At first glance, it appears the company doesn’t take cheating seriously or it would have been on alert for it after the first scandal. However, EY insists it’s serious about cheating. It circulated messages after 2016 and 2017 cheating scandals saying such behavior could result in termination.

Still, the SEC settlement noted EY lacked “sufficient controls in place” to guard against cheating.

As a result, EY is paying a $100 million fine–the largest SEC levy against an auditing firm. And both EY and SEC are continuing additional investigations of cheating.