Paine Publishing

Last month in these pages there was a discussion of how quickly brands and organizations should react to PR crises. An immediate reaction is rarely advisable, although in situations where public safety is involved, speed is critical. We’ll look at such a case below.

In most situations, though, communicators are urged to spend time monitoring the social and traditional media conversations before responding. How much time they should take to do this is where art mixes with science.

A survey earlier in the year from Bospar PR and Propeller Insights asked 1,000+ American adults how long is too long for companies to respond during a crisis. 35 percent said companies should respond within 24 hours; 29 percent said a response within 48 hours was proper; 16 percent said 72 hours; 10 percent said companies should respond within one week.

On Sept. 28, Facebook released news of its data network breach, revealing that the information of 50+ million users was “directly affected.” In contrast to other data breaches (remember Equifax?), this one was announced promptly; Facebook discovered the breach just three days prior to its announcement. It deserves credit for that.

The Quiet Breach

The news, of course, barely made a dent in the consciousness of most Americans, since the compelling events surrounding the Kavanaugh brouhaha sucked most of the oxygen from the news cycle.

Facebook dodged a bullet, at least for now. No doubt the story will get more coverage and attention soon. In fact, just one day after the announcement, on Sept. 29, media reports appeared about the first lawsuit being filed against Facebook for the breach. The complainants contend that in light of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which came to the public’s attention in March 2018, Facebook should have done more to protect user data.

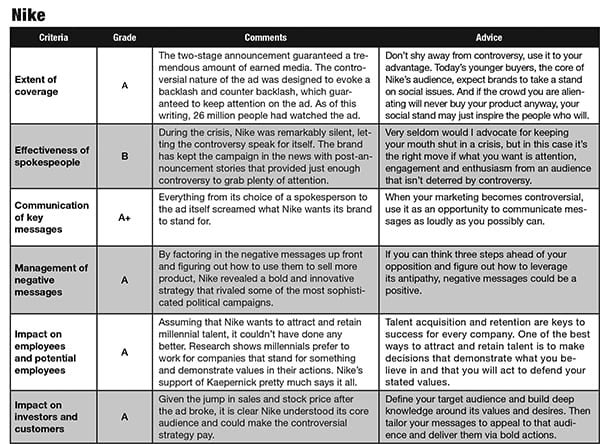

This month we examine two examples of crisis communications in which timing made the difference between success and disaster. When Nike released its controversial ad featuring Colin Kaepernick, the athletic brand said nothing in the face of a tweetstorm of controversy; its silence may have contributed to the success of the campaign.

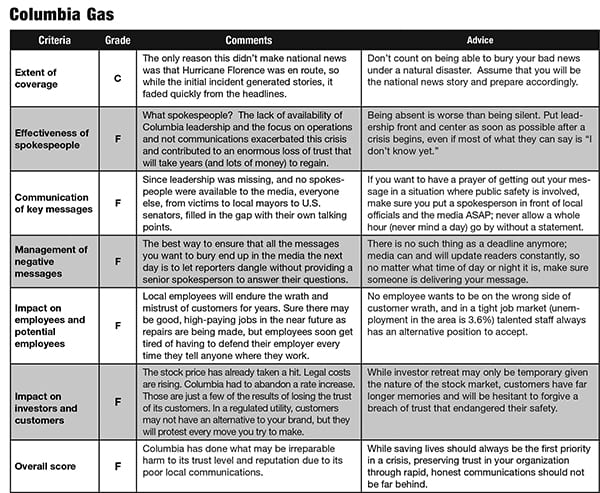

When houses of Columbia Gascustomers in Massachusetts starting catching fire and exploding, Columbia was equally silent. Its silence exacerbated the crisis.

Nike

One of the most publicized and debated brand moves in the last few years erupted in controversy when Nike announced that it would use former 49ersquarterback Colin Kaepernick in an ad celebrating the 30th anniversary of the “Just Do It” campaign.

While Nike had Kaepernick under contract for several years, he hadn’t appeared in any ads since he stopped playing football, which is a story in itself. While some at Nike wanted to cut their losses when it came time to renew the former player’s contract, the head of communications convinced leadership to keep Kaepernick on its roster.

The announcement ignited the expected response from conservatives who objected to Kaepernick’s kneeling during the National Anthem. Within minutes, social networks were full of pictures of people lighting Nike shoes on fire and cutting Nike logos out of socks and clothing.

Nike Expected Resistance

This was part of Nike’s strategy, however. The brand expected the anti-Kaepernick portion of the audience would come out swinging hard in the 24-48 hours after the ad campaign was released, according to an interview with a senior leader at Nike. The brand hoped the response would in turn activate free speech and social justice supporters and thus strengthen the Nike brand for its target audience.

It worked. One thing everyone agreed upon was that the release generated a ton of earned media and influencer support that significantly augmented the paid campaign.

In addition, skeptics were soon silenced when the company posted a 31 percent jump in sales volume and since then has sold a reported $6 billion worth of merchandise. One investment analyst called it a “stroke of genius.” In the weeks after the ad launched, Nike’s stock price has consistently seen record highs.

Know Your Target Audience

Even more interesting was seeing how the ad performed with Nike’s high-priority younger audiences. ABX, an advertising testing company, put the ad in front of its panel of thousands of general population consumers. The ABX Index is based on thousands of ads the company has tested over the years. Anything better than 100 is above average, less than 100 is below average.

When it tested the Nike ad on millennials and broke out results by race, the data showed strong likelihood to purchase and recommend, particularly among millennials as well as people who identify as African American and Hispanic. When asked whether or not they’d “recommend” the product, it scored an eye-popping 409 among millennials and 392 among African Americans. When asked about intent to purchase, Hispanics gave it a 261; millennial males of all ethnicities gave it a 242.

There are lessons to learn about how Nike navigated this crisis. The most obvious is that it saw the connection between what its market research data was telling it and the social halo that would be provided by using Colin Kaepernick, a symbol of resistance to social injustice. It also shows the power of image and reputation in driving sales and stock price.

Columbia Gas Company

On Thursday, Sept. 13 at 4 p.m. overly pressurized gas started flowing through the aging gas mains in and under the houses in the towns of Lawrence, Andover and North Andover, Massachusetts.

By 4:20 p.m. houses in those communities began to spontaneously explode, causing 18 fires, the evacuation of thousands of people, and total destruction of dozens of homes. In addition, a teenage boy on his way to a party to celebrate getting his driver’s license was killed when the chimney of a house fell on his car.

The gas line’s operator was Columbia Gas, a subsidiary of NiSource, one of the largest utility companies in the country.

Shortly after the explosions, nearly 10,000 people were told to evacuate—in the middle of rush-hour traffic. Interstate highways were closed, and evacuees were told that their electricity and gas could be off for days or weeks.

Soon National Guard troops were delivering 7,000 hot plates and 24,000 space heaters to customers who would be without gas indefinitely.

Given the size and maturity of the company, and the fact that it had experienced similar crises, one might have expected a classic crisis communications response. There was, however, dead silence from Columbia officials for the first five hours (a year in Twitter time).

At the five-hour mark, it posted a brief notice of the incident on the company’s website. Regular updates didn’t start appearing on the website until the following morning. Company officials failed to appear at the incident command center for 24 hours. It took three days before the CEO of NiSource issued an apology and even longer to grant an interview to a local paper.

Another five days passed before Columbia announced a $10 million donation to the relief fund local authorities set up to help the victims. As another gesture of goodwill, Columbia also announced that it would replace the entire pipeline network, which may take years.

Local Frustration

Clearly residents and local officials were frustrated with Columbia’s tepid response. The mayor of Lawrence called Columbia “the least informed and the last to act” and accused it of “hiding from the problem.”

When 24 hours had passed with little progress, Massachusetts governor Charlie Baker invoked emergency powers and put rival utility Eversource in charge of the incident. Federal investigators were on the scene the morning after the incident.

While gas leaks and explosions are rare, they are an accepted reality within every gas utility company, and most pipeline operators have established crisis communications plans and procedures. Even the CEO admitted the company’s lethargic communications was a mistake, telling a reporter that the entire company was focused on “mobilizing our [operational] responses” to the emergency; communications was put on the back burner. “We could have done better to communicate,” he admitted. “We did everything we could to muster our operational resources. On a scale this large, with the impact we saw, there were opportunities certainly to provide better communication in the early hours. We regret the lack of communication early on.”

In an era of instant communications and Twitter and Facebook as primary news sources, without a commitment to prompt communications, trust erodes quickly, and traditional communications strategies are worthless.

It is clear that Columbia needs to do more than just upgrade its network: it must modernize its culture and how it thinks about communications. Whatever that might cost is a drop in the bucket compared to the ultimate hit to Columbia’s bottom line.

The Cost of Silence

Columbia’s legal and other costs are rising already. Despite the company’s commitment to aid in rebuilding the community, the first lawsuits claiming negligence were filed a week after the incident. Many more have come since. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Edward Markey and House members Joseph Kennedy and Nicki Tsongas have called for Senate Commerce Committee hearings.

Resistance to Columbia’s planned pipeline expansion heated up and generated an active protest group, the Columbia Gas Resistance Campaign, and the project has become a target of another group, Climate Action NOW.

In addition, Columbia was forced to withdraw a rate increase application and shares of parent company NiSource plunged in the days following the explosion, closing 12 percent lower, one day after reaching a 52-week high.

CONTACT: [email protected]