For communicators, emerging concepts and terms in PR are often among the most misunderstood. From Artificial Intelligence and automation to blockchain and cryptocurrencies, vendors and boutique marketing firms that claim to have all the answers often misrepresent these newer ideas. Their hope, of course, is convince communicators to purchase what they present as proprietary solutions and convince us that they really do have all the answers.

One such often misconstrued term is “gamification.” Merriam-Webster defines it as “the process of adding games or game-like elements to something (such as a task) so as to encourage participation.”

Since British software engineer Nick Pelling introduced the word in 2002, it has widely been used in a marketing and PR context. Gamifying around a product launch, a brand awareness campaign or internal communications messaging not only encourages participation, but engagement, too. Adding the aforementioned “game-like elements” to your brand or message offers incentives for members of your target audience to interact with it.

The Evolved Definition of Gamification

This is a far cry from what Pelling envisioned when he coined the term. “The things I was thinking about way back then were less to do with adding [medals] to websites than to do with the megatrends of the day—specifically, high-interactivity user experiences and digital content platforms,” he told PRNEWS in an email. “Both of which then made Apple the most valuable company in the world.:-/”

Pelling’s original definition of gamification certainly has evolved. In recent years, we’ve seen gamification at work with McDonald’s’ annual Monopoly contest, wherein game pieces come with certain menu items that can be combined to win big prizes.

We’ve seen it with Amazon’s exclusive, invite-only Vine program. Here, select customers are given free merchandise if they meet a quota for timely reviews on select products.

Gamification is at work in any quiz, contest or interactive ranking exercise that a brand or organization uses with its audience. And, as we noted above, it’s used often to entice employees to engage with a company’s internal communications.

Seems Innocent Enough, But...

When used as a marketing or PR tactic, the gamification of a campaign seems fairly tame on the surface. When the gaming element of competition is applied, however, things get ethically hairy. PR can go a long way in generating awareness or engagement around a campaign by pitting products, services or values against others.

When used to encourage audiences to compete against each other or further controversial motives, however, game-based competition can quickly escalate and turn ugly.

Over the last several years, the ACLU has been monitoring China’s gamification of its citizens. China’s people are assigned “social credit scores” in what’s become known as Project Sesame.

Mandatory Games in China

“Everybody is measured by a score between 350 and 950, which is linked to their national identity card,” the ACLU wrote in 2015. “While currently [it is] supposedly voluntary, the government has announced that it will be mandatory by 2020.”

“In addition to measuring your ability to pay, as in the United States, the scores serve as a measure of political compliance. Among the things that will hurt a citizen’s score are posting political opinions without prior permission, or posting information that the regime does not like, such as about the Tiananmen Square massacre that the government carried out to hold on to power, or the Shanghai stock market collapse.”

“It will hurt your score not only if you do these things, but if any of your friends do them. Imagine the social pressure against disobedience or dissent that this will create. Anybody can check anyone else’s score online. Among other things, this lets people find out which of their friends may be hurting their scores.”

While some think that concerns over Project Sesame have been blown out of proportion, others are concerned with the precedent that gamification of “social credit” sets for Chinese citizens.

Games for Serial Killers?

After the recent horrific El Paso shooting, conflict journalist Robert Evans noticed that the far-right message board the shooter frequented, known as 8chan, had been a hotbed of radicalized domestic terrorists who hoped to one-up each other with kill counts. They referred to their kill counts as high scores.

In “The El Paso Shooting and the Gamification of Terror” (Aug. 4, 2019, Bellingcat) Evans includes screenshots of the message board that show the extent to which gamification can go horribly wrong. He arrives at a sobering conclusion: “The act of massacring innocents has been gamified.”

“Can gamification be used to manipulate and control people? The answer is absolutely yes,” Karl Kapp, a professor of instructional technology at Bloomsburg University in PA, and who is known as an authority on gamification, tells PRNEWS, “Because the whole idea of gamification is motivation and behavior change. If the motivation and behavior change that you want to encourage is not positive, then you can kind of make some inroads there.”

Implications for Communicators

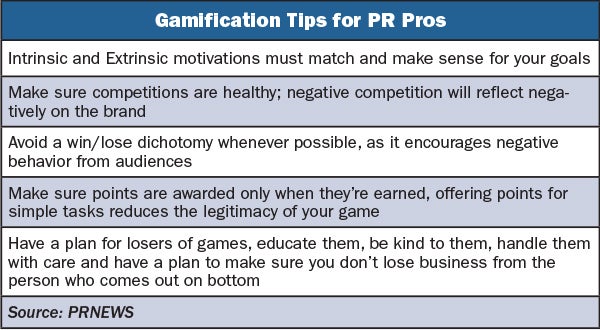

What can communicators do to make sure that we’re encouraging the proper motivation and behavioral change when we gamify our campaigns? For that, we must look at the root of how gamification influences audiences and learn about its potential areas for ethical abuse.

Be Mindful of Intrinsic Motivations

As with most things involving PR, the intentions of those launching the campaign largely dictate the effect that gamification can have on your audience. Kapp refers to these effects as “motivations.”

“When you’re talking about gamification, there are two elements of it—intrinsic and extrinsic,” he explains.

“Extrinsic is [when], if I do something I earn some points, and if I own own enough points I can buy something. But most of the time, the extrinsic motivation doesn’t work by itself. You need something internal, an intrinsic motivator.”

“So if you’re not intrinsically motivated to do harm to somebody, gamification is going to have a long, long road to try and actually change that behavior and may not be able to do it,” Kapp continues. “But if you’re already inclined because of the social or cultural organization that you’re in with, if you’re hanging around in 4chan or 8chan…”

Danger: The Need to Escalate and ‘One-up’

Kapp explains that he has never seen gamification that was intended for good suddenly veer off in a weird direction. What’s far more, common, unfortunately, is the need to keep that external motivation remain strong by escalating it.

“In order for external motivation to continue to work, you need to continue to up what that motivation is,” he explains. “Pay is a good example—if you’re doing a job for five years, you might be OK with a certain rate of pay, maybe no increase. But if you want to stay around five more years and you’re not really finding the job fulfilling, that’s when you want a raise. You have to keep upping the ante of external motivation to get people how to behave how you want them to behave.”

A ‘Win-Lose’ Dichotomy

So many celebrities and people in power triumph a Machiavellian worldview where success is measured solely in wins. This win-lose dichotomy has been weaponized against audiences in everything from politics to lifestyle marketing.

“That’s the ‘winner take all’ mentality,” says Kapp. “It’s not good in politics and it’s not good if you’re in marketing or PR either. You’re gonna have some raving fans, but you’ll also have some raving anti-fans.”

Abusing the Word

Moreover, Kapp stresses that gamification is about much more than creating winners and losers. The word itself is misused. “It’s abused a lot—a lot of people say they’ve gamified their product if you get ten points for logging in,” he says.

“But nobody cares—if the points don’t mean anything, if there’s no value behind them, no intrinsic motivation, then you’re...wasting their time and making them feel that your app is childish.”

Mind The Losers with Bonuses, Resets

This dichotomy also sets up some of your audience to be at the bottom of the hierarchy—how do you handle those people and still keep them engaged with your brand now that they have been labeled as losers?

“Be aware of these unintended consequences,” warns Kapp. “If you gamify something, you’re gonna have losers. What are you gonna do with them?” Depending on your PR goals, it might be wise to allow the losers to recover.

Kapp has seen people in a gamified environment who don’t achieve what the majority does become frustrated, disengaged or checked out altogether. “They can end up hating your brand because you’ve put them in a situation where they feel like they’ve lost,” he says.

“Maybe in that case you reset the contest every week so everyone has a new chance to win.” Another tactic is to institute bonuses. This allows those low on points to do something that earns them bonus points.

“But if someone feels that they haven’t been successful in a contest, more often than not they’ll just drop out, angry or upset.” That, of course, can leave a bad taste in the mouth of your target audience.

CONTACT: JJoffe@prnewsonline.com