[Editor’s Note: With PR News’ CSR and Nonprofit Awards luncheon coming March 15, we look at two brands taking stands, though they do so in contrasting ways. For those readers interested in attending the luncheon, please contact Carol Brault (cbrault@accesintel.com) and ask for your 33 percent discount as a PR News subscriber. ]

It was just more than one year ago, in mid February 2018. The country’s biggest story was the fatal shooting of students and teachers at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL. In response, students were organizing protests against companies doing business with the National Rifle Association (NRA). Delta Air Lines was on the list. It offered a 2-10 percent discount on airfare to NRA members.

When the issue rose to the level of Delta CEO Ed Bastian, he was unsure of why the carrier even offered the deal, according to the NY Times. Since the deal meant almost nothing in revenue terms—very few additional tickets were sold as a result of it—Delta made “a quick decision” to drop the NRA discount, Bastian told the Times. That move “wasn’t an anti-NRA stance or pro gun-control stance,” he added.

The Reluctant Social Advocate

SVP, Corporate Communications

Univision

Yet in the glare of the debate following Parkland, Delta’s decision became enmeshed in politics. In Georgia, Delta’s home, legislators were debating killing a steep tax on jet fuel. Rescinding the tax would mean a $40 million savings for Delta.

But the NRA wanted to punish Delta for cutting ties to the organization. It pushed lawmakers in the Republican-held Georgia house and senate to keep the tax.

In the run-up to the vote, Delta refused to change its mind on the NRA discount. The issue then became personal. “It was more than a business decision for me,” Bastian said. “You try to detach your personal emotions from your business, but there’s a point where you can’t anymore.” It was at this time that Bastian raised the stakes, making Delta’s move a political issue. “Our values are not for sale,” Bastion said at the time.

Fine, said Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle, a Republican. “Businesses have every legal right to make their own decisions…[but] corporations can’t attack conservatives and expect us not to fight back,” Cagle said.

Lawmakers reinstated the tax, which flew through the Republican-controlled chambers and Delta had a $40 million bill to pay.

The story ended well for Delta, though, since then-governor Nathan Deal, also a Republican, signed an executive order rescinding the tax. Earlier this year new GA governor Brian Kemp signaled he’s in favor of extending Deal’s order.

Still, the story illustrates the risk involved when business and socio-political issues get mixed. It also shows why many brands prefer to steer clear of hotly contested issues.

Nike’s Calculation

Contrast Delta’s reluctant activism with Nike’s decision to stand with Colin Kaepernick in his battle, which began as a fight against racism and eventually included the right to protest during the national anthem. In addition to paying Kaepernick for endorsing Nike products, the brand also made a donation to his foundation, signaling its support for the athlete’s social agenda.

Its endorsement of Kaepernick resulted in igniting the wrath of the president and his base. Smartly, the brand did its homework prior to the endorsement. While it knew some of its customers would turn against it, Nike calculated correctly that most of customers would embrace the campaign. The brand’s summer sales broke records and its share price spiked.

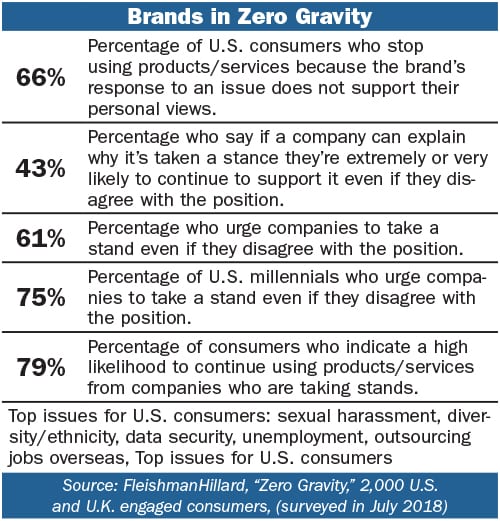

Brands know they can’t remain on the sidelines forever. Research argues that consumers, particularly millennials, insist brands represent more than their products and services.

In a 2017 survey of 1,000 “hyper-aware and influential consumers,” APCO Worldwide found 90 percent of them expect companies to be involved in taking on society’s most pressing issues. 71 percent told APCO it is acceptable for companies to do so even if it is controversial issue. And 95 percent believe companies have the ability to create a better society. Most important, of course, is some research shows consumers will drop brands that fail to speak up.

Risk Assessment

Still, for most brands, even those who are socially active, taking a stand on a socio-political issue is a calculated risk that’s loaded with potential pitfalls (just ask Delta). And questions abound. When should a brand take a stand? How should it do this? Who should speak up? How do you decide which issues are worthy of a fight? And while it can be great to take a stand, how many stands are enough? In other words, at what point do too many stands distract a brand from serving its customers?

The answers to these questions aren’t easy. A recent study from FleishmanHillard describes the brand’s dilemma as “zero gravity.” By its definition, zero gravity is “an issues-laden environment that quickly tests corporate values…it’s the zone where every issue in the spotlight feels like a competing force, pulling [brands] in equal and opposite directions. A place where [companies] can’t find [their] footing because the options are loaded with real business risk.”

[Note to Subscribers:FleishmanHillard’s report is available in the PR News Subscriber Resources Center.]

Standing Up or Sitting Down

Bobby Amirshahi understands this territory well. He’s SVP, corporate communications, at Univision, which took its first big stand in 2015 when Donald Trump, then co-owner of the Miss Universe pageant, called Mexican immigrants “criminals and rapists.” At the time, Univision was a partner with Trump in televising the pageant. The network pulled out of the partnership quickly.

Univision has since become known for its activism, yet Amirshahi quickly notes, “We’re a for-profit company…and we definitely run a risk” of alienating partners “when we take a stand.” Univision’s partners are crucial to its business; they are advertisers as well as media companies that pay for the right to carry its television content.

In addition, the company’s target audience has multiple media choices. Antagonizing its audience would be disastrous for Univision.

Amirshahi continues, “Do you take a stand on every single issue that affects your core consumer?” If you did, “you could create so much noise around your brand that it distracts from the way you actually serve your audience.” He sums up the situation well, “Knowing when to stand up and when to sit down…is the hardest thing” to decide after a brand begins to take stands.

The company’s mission statement, he says, helps it determine what issues to back. Univision “stands up on an issue when it directly concerns or impacts our community in this country,” he says. Amirshahi and his colleagues do a lot of homework around social issues Univision is mulling. A decision to engage rarely is a slam-dunk.

For example, Amirshahi concedes Univision took “a tremendous risk” last year when it opposed the White House’s stance on the immigration policy known as DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. Univision’s activities included filing amicus briefs, initiating a social media effort and organizing against the planned citizenship question in the 2020 Census.

Internally, Univision immediately told its employees it would pay legal costs should they need to fight against the administration’s policy. “We don’t see a divergence in being for-profit and standing up for Hispanic America…we can do both,” he adds. Indeed, the network’s TV ratings rose after the DACA stance, per Amirshahi.

Internal Communications

Another aspect of Univision’s internal communications on social issues has the company “almost always communicat[ing a stance] to our employees before or, if necessary, at the same time as making a position public,” Amirshahi tells us.

When there’s a chance partners might look askance at a position Univision takes, “We post more in-depth explanations on our policy blog or carefully select media outlets and reporters to whom we tell our story and explain our rationale.”

It’s working. Amirshahi says Univision’s ratings improved after its DACA stand and have remained strong.

Sales and Stands

PR Media Maven

Ben & Jerry’s

The situation is almost totally different for Lindsay Bumps, PR media maven at Ben & Jerry’s (yes, that’s really her title). At the start of a presentation she describes the company as “an activist brand that just happens to make incredible ice cream.”

For Ben & Jerry’s, sales “are an important KPI, but not the most important.” More important, she says, are KPIs that measure how much of an impact a social initiative makes. “Did we effect change?” How many signatures did a brand-backed petition receive? In terms of social media KPIs, the brand looks closely at impressions, but also at engagement. “Did we engage with the right audience” to make a difference on an issue? Such questions are discussed and reported on during daily, weekly and 30-day interactions (emails, phone calls or meeting) with senior executives, she says.

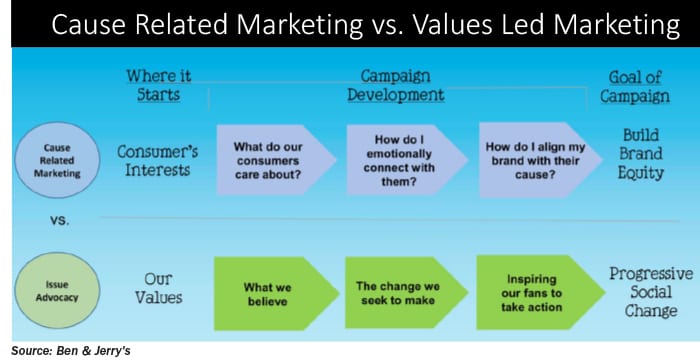

While many of its social campaigns have an ice cream component—Save Our Swirled, or SOS, the brand’s first global flavor, was the centerpiece of a climate change effort—“we don’t do these campaigns for sales.” It’s the difference between marketing for a cause and marketing for sales (see graphic).

For the record, the campaign resulted in 60,000 signatures on a global warming petition that was presented to world leaders. And for those of you keeping track, Save Our Swirled features raspberry ice cream, marshmallow and raspberry swirls, plus dark and white fudge ice cream cones. One of the taglines was, “If it’s melted, it’s ruined.”

Noise is Not an Issue

It might sound as if Ben & Jerry’s takes a stand on nearly every issue that reaches the company. While the brand pushes numerous causes, it doesn’t do so willy-nilly. “Our mission and values” guide us, Bumps says. When “something is happening that negatively affects our mission and values we will speak out.” Yet there are some occasions when the brand decides not to take a stand. For example, it didn’t comment on certain “live-shooter” incidents, she says.

Unlike Unvision, though, creating too much noise with socio-political stands “is not an issue” for Ben & Jerry’s, she says. “We’re not afraid to speak out when we need to…we do it with our brands in mind, but also thinking about the impact we can have on any given issue.”

In addition, there’s what she describes as a “formally informal” decision-making process to pick which issues and organizations to support. “We’re fortunate” in that all members of the cross-functional decision-making committee sit in one building. Usually two members each “from our social mission team, leadership team, PR team and franchise team” periodically discuss “what impact it will have if we choose to speak out or not to speak out.” While there’s “definitely” involvement from the CEO, CMO and COO, though this trio of executives does not make the decisions “by themselves.”

The group meets regularly to tackle yearlong social initiatives, such as marriage equality and GMO labeling. It also gathers as needed when a pressing issue arises.

Reporting to the C-suite is fairly conventional. The brand uses email, phone calls and memos at 24-hour, seven-day and 30-day intervals. In addition there are more formal reports made to the C-suite.

In the end, Bumps realizes she’s in an unusual situation and is “very fortunate” to be at a company where products, sales and social activism sit “side by side” in terms of importance. Still, she urges other brands to be “unafraid about speaking out…don’t let risk prevent you.”

CONTACT: kefernandez@univision.net Lindsay.Bumps@benjerry.com