There are more pleasant things to do than pay insurance bills, particularly when the money could be used for other needs. The bill-payer laments she’ll never need to use the insurance, why pay it? Still, if she’s smart, she pays.

Brands’ preparation for PR crises is similar. It can be a hard sell to convince executives to devote valuable financial and human resources to PR crisis preparation. Still, odds are that a crisis will touch nearly all businesses. Deloitte’s 2018 Global Crisis Management Survey showed 80 percent of crisis-management teams were mobilized in the past two years. Those brands with crisis plans and crisis-practice regimes should fare better. The last thing you want to do during a crisis is to begin formulating a crisis-response plan. The prudent company prepares in advance, figuring it’s akin to having an insurance policy.

To gauge attitudes toward advanced crisis preparation, pain points and the use of technology during a crisis, PR News and Crisp, a social media issue detection and crisis monitoring firm, surveyed 400+ PR executives last month.

Crisis and Bottom-Line Concerns

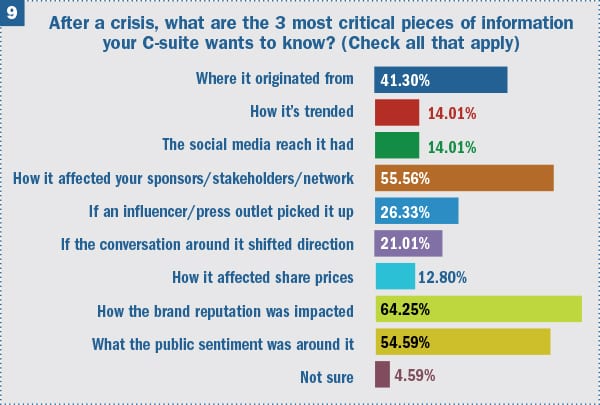

What emerges from the survey, said Emma Monks, Crisp’s VP of crisis intelligence, is how a crisis affects the bottom line. The data the C-suite considers most important after a crisis (see Chart 9) “relates to money and customers,” she said. “You can get wrapped up in all sorts of things during a crisis, but at the end of the day, it’s all about financial impact.” How the crisis influenced brand reputation (64 percent), impacted stakeholders and others (56 percent) and changed public sentiment (55 percent) were the top information the C-suite requests after a crisis, the survey shows.

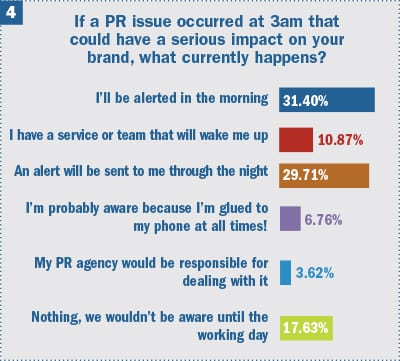

Monks interpreted the data in Chart 4 as signifying that too many brands are too slow to react to crisis. The chart shows nearly 50 percent of communicators saying that they’d be notified of a significant after-hours issue the next day. “If you’re reacting to a crisis the next day,” she said, “you’re already behind.”

Also reactive, she says, is the preponderance of manual monitoring (67 percent) of breaking PR issues online (see Chart 6). [Monks’ dislike of manual monitoring is discussed below.]

Plan in Place

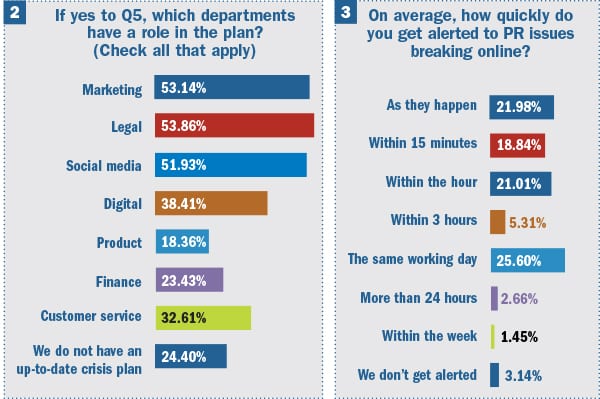

It’s encouraging that 60 percent said they have an updated crisis communications plan (Chart 1); 32 percent said their plan is “continually updated” and 28 percent responded it’s had “a recent update.”

This is a better result than in previous surveys. In 2016 PR News and Nasdaq found that only about 50 percent of companies had crisis plans.

The increase in plans seems to demonstrate a rise in crisis’ importance. This is not a surprise. The volume of PR crises appearing in media headlines has risen. In addition, social media’s ability to destroy a brand’s reputation speedily should prompt crisis preparation with great vigor.

Still, 14 percent of communicators told us “we don’t have” a plan. Adding those respondents to the 12 percent who said their plan hasn’t been “updated in more than one year,” and the segment that said it hasn’t been revised during “the last six months” (6 percent), brings the unprepared and out-of-date to 32 percent, which is significant.

Of course, having an updated crisis plan is just part of the battle. Only those with a current plan, a monitoring regime and a periodic crisis simulation schedule are on the path to good crisis preparedness.

Integration

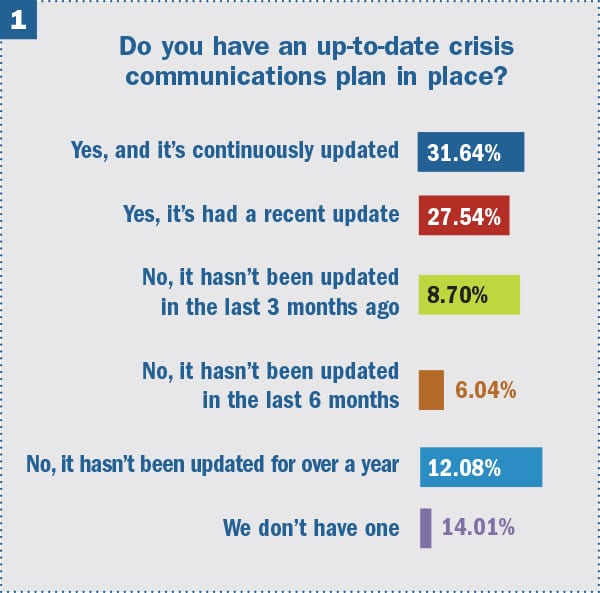

Chart 2 also seems encouraging in that it shows an integrated response to crises. Note that only communicators who told us their companies and organizations have updated crisis communications plans (Chart 1) were asked to respond here.

As is seen in Chart 2, marketing (53 percent), legal (54 percent) and social media (52 percent) are the most involved, though digital (38 percent) and customer service (33 percent) also are integral.

Monks’ issue with this question is that “communications” isn’t one of the responses.

The Importance of Speed

As digital technology and social media proliferate, the role of speed in crises has become critical. As such, some of Chart 3’s results are encouraging. A total of 22 percent said they hear of events “as they happen,” 19 percent said “within 15 minutes” and 21 percent “within the hour.”

The concern is that more than one-quarter of respondents (26 percent) said they hear about breaking PR issues “the same working day” they occur. In an environment where seconds can make or break a brand’s reputation, that’s still too slow.

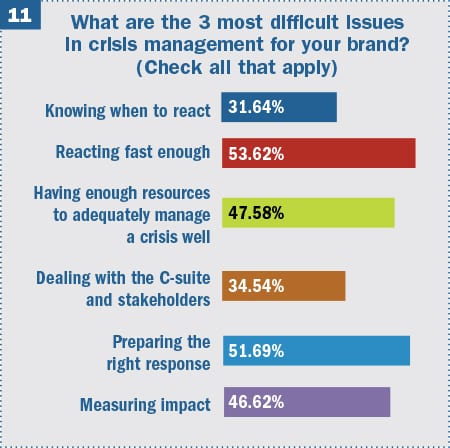

Similarly, the emphasis on speed is a pain point for communicators when dealing with a crisis. Notice that more than half of respondents (54 percent) chose “reacting fast enough” as their top crisis issue (see Chart 11).

Continuing the discussion about speed, Chart 4 seems disappointing in that just 30 percent of communicators are alerted during the evening when a “PR issue that could have a serious impact on your brand” occurs after hours, and only 11 percent have a service that wakes them.

With the 24/7 news and social media cycle, it seems risky to leave your brand exposed during off-hours.

Monks is concerned with the 49 percent who will be alerted in the morning/the next working day. “You’re already starting on the back foot” when you wait until the next day to begin working on a crisis response, she said.

Other Pain Points

Looking at other difficulties illustrates much about modern PR crises (see Chart 11). Besides the already mentioned “reacting fast enough” (54 percent), the top three most difficult issues are “preparing the right response” (52 percent), “having enough resources to adequately manage a crisis well” (48 percent) and “measuring impact” (47 percent).

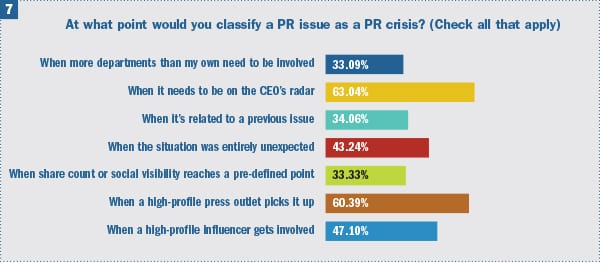

Note the significant numbers for “knowing when to react” (32 percent) and “dealing with the C-suite and stakeholders” (35 percent). Knowing when to react relates to the difficulty of knowing if you are in a crisis. “A crisis plan works best when it first defines what a crisis looks like for your brand,” Monks said.

Those who’ve worked in a PR crisis can identify with 35 percent of respondents who picked “dealing with the C-suite” as a major pain point. C-suite executives often approach a crisis from various vantage points. Getting them to agree on a response can be as difficult as crafting the response itself.

Resources

The difficulty that surprised Monks and us was “having enough resources to adequately manage a crisis well,” which seemed high at 48 percent. Considering the potential destruction a PR crisis can bring, it’s surprising to see resources lacking for crisis. Monks and we believe respondents were referring to inadequate human resources.

[We encourage you, the reader, to let us know what resources, if any, may be lacking in your crisis-response regime. Is there a deficit in human resources, technology, experience or something else? Please email editor Seth Arenstein at: sarenstein@accessintel.com]

The response about resources (Chart 11) is slightly at odds in light of the results in Chart 10. Here an overwhelming majority (79 percent) said their CEOs were “very willing” or “somewhat willing” to invest in “strong crisis preparation.”

Manual Monitoring

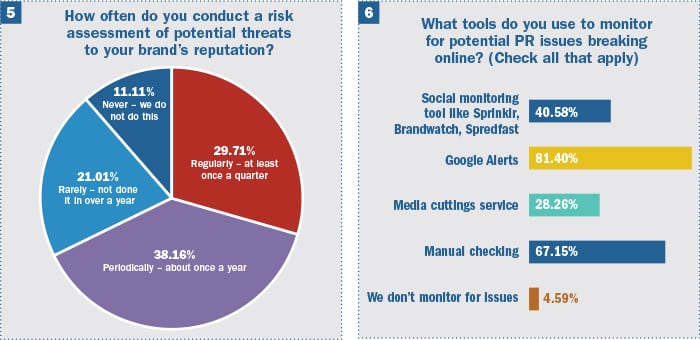

Arguably the most disturbing data came in the responses seen in Chart 6, though there was at least one positive: the results show the majority of respondents are monitoring social for potential issues. They also are doing so with tools, such as Google Alerts (81 percent) and social media products, such as Sprinklr, Brandwatch and Spredfast (41 percent). Those who said they aren’t monitoring was minimal (5 percent).

The potential downside here is that 67 percent said they are monitoring manually. “That’s kind of scary,” Monks said. “Who’s doing the monitoring?” she asks. Do they have the skill level necessary to do it well? Another concern is the monitoring's consistency. “What if [the person doing the monitoring] has a busy day or is swamped, does the monitoring get done that day? What about holidays and off-hours?”

“Manual monitoring likely means Google Alerts and searches,” she said, but “that means you’re missing a lot of data sources...no one tool has a monopoly on data sources.”

For Monks, “it’s incredibly dangerous” to monitor only with tools or only manually. “Machines aren’t great” at interpreting sentiment, for example. And, as noted above, human-only monitoring can be inconsistent. A mix of humans and tools is the best option, she said.

‘Shocking’ Risk

The importance of risk assessment has risen in crisis-management circles. One factor to explain this is the rise of influencers, who can help brands with third-party validation and authenticity, but can also go off script—personally or professionally—and inflict significant reputation damage.

As you can see in Chart 5, a solid majority (68 percent) of respondents said their companies are “regularly” or “periodically” conducting risk assessments of potential threats. On the other hand, it is troubling that more than 30 percent told us their company “rarely” or “never” conducts a risk assessment of potential reputation threats. “That’s shocking,” Monks said. She believes the 11 percent who said their organizations “never” conduct a risk assessment “might be unaware that it’s being done.”

In sum, the study shows improvement in preparation for crises, though it indicates there is room for improvement. Again, planning, practicing and monitoring are key.

A version of this story appeared in the March 2019 edition of PRNEWS. For subscription information, please visit: http://www.prnewsonline.com/about/info

Seth Arenstein is editor of PRNEWS. Follow him: @skarenstein

CONTACT: partnerships@crispthinking.com