Influence operations on social media that target politicians, voters and elections have proliferated. Russia’s hacking of the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign is a notable example.

But influence operations are infecting the commercial space too. Companies increasingly find themselves and their brands under assault, often from anonymous sources. These actors try to stealthily sway public opinion and consumer preferences.

For brands, manipulation of conversations and debates on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and other social media platforms can influence the bottom line. The effects range from annoying but largely neutral to serious and incredibly adverse. Companies need to consider their vulnerability to such operations.

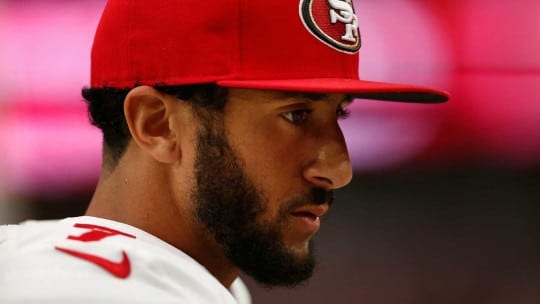

Nike came under digital attack—a coordinated, operational campaign, not solely angry rhetoric—after it rolled out the Colin Kaepernick campaign last September. Goals of this cyber attack included driving down the company’s sales and share price, according to a technical study we conducted with Eran and Roni Reshef of Morpheus Cyber Security.

Sports to Politics

The ad campaign re-ignited debate over Kaepernick's kneeling protest. The story was pushed off the sports pages into the political arena when President Trump tweeted his opinion of the issue.

Nike’s share price fell 3.2 % the day after the campaign debuted. Many social users called for a boycott of the company. Some filmed themselves destroying Nike products.

Our study of Twitter traffic illustrates that the consumer and political outrage against Nike wasn’t nearly as voluble or widespread as it initially appeared.

Indeed, certain groups bolstered the debate online. Some created inauthentic Twitter surges. Their tactics included closely organizing echo chambers to mobilize tweets or deploying computer-generating traffic with bots. In the study, an inauthentic source for Twitter traffic is called a nasnas, an Arabic term referencing a mythic devilish provocateur.

Analyzing Twitter traffic during the first week after the advertisement aired, we identified a sample of 668 users who were attacking Nike for its Kaepernick campaign. Each posted at least ten negative tweets or retweets. These users, however, didn’t maintain their campaign for long. By September 19, fewer than 10% were still vocal about the topic.

This chart tracks the number of users posting negative tweets about Nike. Source: Morpheus-APCO

Inorganic Traits

Further inspection of the active users revealed that 426 out of 668 sampled users were nasnases, or ones that exhibited inorganic traits. Such traits include tweeting or retweeting more than 50 tweets a day, mostly about political issues. Comparing the number of total tweets an account has posted relative to the account's creation-date can also reveal inorganic traits; for example, if an account was created in March 2018 but has posted hundreds of thousands of tweets, the account is likely a nasnas.

In addition, several groups were promoting the boycott against Nike. Some sought to organize an echo chamber of like-minded supporters to promote a ‘tweet pack’ of content that assailed Nike and the Kaepernick ad. One group's website suggested that users wait a few minutes after posting the first pack of ten tweets before posting the next pack of ten. This was probably to avoid a suspension from Twitter.

One of the coordinated influence campaigns was short in duration. It had 300 users and generated about 2133 tweets and retweets. Fifty-eight of those users were also part of the sample group in our study.

Furthermore, analyzing the connections between the core sample group of 668 actively negative Twitter users shows heavy connectivity and coordination among them. 94% of these users are connected to at least five other users among the group. This helps create an echo chamber of accounts, working together to generate impact on Twitter through coordinated means.

Just Do It, Briefly

As the graph above shows, the campaign against Nike petered out after only two weeks. At this point, it became clear that the Kaepernick ad never really posed a serious challenge to Nike. It is a case of an influence operation that was largely unsuccessful.

The Takeaways

Perhaps counterintuitively, companies could leverage the attention generated in these situations. In Nike’s case, the Kaepernick ad helped the company. Its share price quickly rebounded and rose to an all-time high by the end of September. The company also announced a 10% increase in sales during the summer quarter. Vox reported that Nike experienced a $6 billion boost in overall value post-Labor Day.

The study shows that in the new digital economy, sentiment toward companies and brands isn't always as it seems; social media conversation is not necessarily a bellwether.

Similar to activities in the political space, amorphous actors may attack companies for competitive, financial or even political reasons—and companies need to consider how such influence operations may affect their bottom line.

Technologies exist that can expose the method and even the motive behind such operations. Not only that, new technologies can even counteract them. Once brands understand who or what is trying to stir up a debate on social media, they can begin to respond.

The Nike example shows that companies, if smart, can counter influence operations and prosper. Nike stood its ground, doubled down on Kaepernick, and saw sales rise. It's important to note Nike seemed to understand the threat to its bottom line was minimal and artificial.

A former chief foreign correspondent for The Wall St. Journal, Jay Solomon is a senior director at APCO Worldwide. Aftan Snyder is a senior consultant at APCO.