With apologies to the English punk band the Clash, the song “Do I Stay or Do I Go?” seems more complicated now than it was when the tune was released, in 1982. On the face of it, the title seems like a yes or no question. Yet Do I Stay or Do I Go? no longer applies for some multinational companies doing business in Russia.

You might have heard or seen Yale Business School professor Jeffrey Sonnenfeld discuss his list of companies staying in or departing from Russia. It’s a staple of TV and print media reporting on Ukraine.

Initially, even Sonnenfeld ‘sang’ with the Clash: businesses either stayed in Russia or exited. Simple. Neat. Of course, his first list, compiled four days after the Feb. 24 invasion, contained fewer than 30 companies.

However, the song sheet is more nuanced now, resulting in communication headaches.

For instance, Sonnenfeld’s compilation is no longer two rosters: staying or going. Instead, the list of some 600 companies has five gradations. These extra categories help Sonnenfeld and his team of researchers and students include so-called half-exits and other variations.

Pass-Fail

Ever the professor, Sonnenfeld assigns grades to companies on the list based on where they're grouped.

For example, some companies say they are remaining in Russia, but won’t expand or fund new business. AstraZeneca has halted “new investments and new clinical trials.” Hospitality brand Hilton has “suspend[ed] new investment and close[d its] corporate office.” Those companies are in the Buying Time group of 75 firms. Despite halting new ventures, they continue doing “substantive” business in Russia, Sonnenfeld says. Grade: D.

There are 41 companies, graded C, in the Scaling Back contingent. They’re maintaining some business ventures and reducing others. For instance, Amadeus IT Group stopped work with Russian airline Aeroflot. Liquor brand Bacardi “paused exports to Russia, but not domestic operations.”

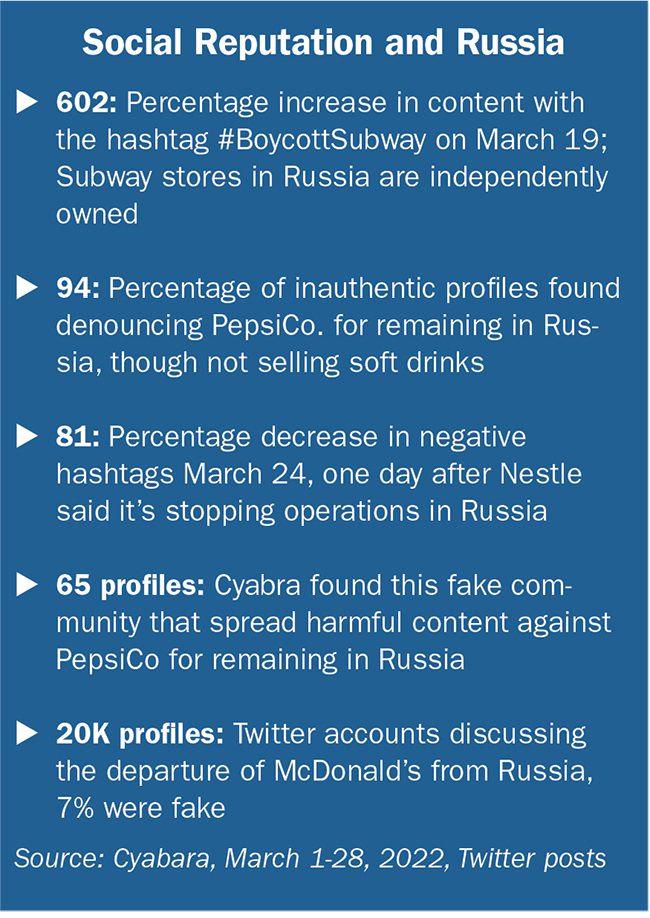

And Sonnenfeld’s a tough grader. McDonald’s and IBM are among 217 companies in the Suspension category. They receive a B since they’re keeping options open for a return, though they’ve “temporarily curtailed most or nearly all operations.” Most of the McDonald's outlets in Russia are company owned. The brand was hailed for suspending operations early in March. On the other hand, Subway has a slew of franchisees in Russia who've remained open. As a corporation Subway is taking a hit on social media (see chart).

The Phi Beta Kappa of companies, for Sonnenfeld, at least, receive an A. As of April 4, 220 are in the Withdrawal category. They’ve exited completely or halted operations totally. Examples include Bose, KPMG, Shell and WeWork.

As you’d expect, the 100 companies that are Digging In and refusing to leave Russia receive Fs from the professor. These include Koch Industries, Krispy Kreme and Red Bull.

Communication Issues on Russia

Two major issues worry communicators.

- First, what happens to the reputation of a company that remains in Russia for what it believes are legitimate reasons? And how does one communicate this?

- Second, what about companies that talk the talk, but don’t quite back up their words with action?

Let’s look at the first issue. On the face of it, you could argue some companies have good reasons for receiving poor grades from the professor.

For example, a number of pharmaceutical firms say they must remain in Russia since their products, such as medicines, are essential. Russia’s citizens, these companies say, had nothing to do with the invasion of Ukraine and should not suffer as a result of it.

Similarly, companies in the food industry that remain in Russia say citizens would suffer from their departure. Procter & Gamble and Nestle SA, for instance, say they provide basic items such as milk and diapers. Sonnenfeld grades both a D.

Other companies claim abandoning operations is potentially financial suicide, especially since Russian leader Vladimir Putin said last month he favors nationalizing assets of uncooperative foreign businesses.

This argument has an employee-safety corollary. Besides nationalizing assets, Putin also threatens to jail executives and perhaps employees of businesses that depart.

Employee Risk

As a result, some of these companies claim they must maintain a presence in Russia to minimize risk to their employees. Indeed, officials of McDonald’s, Coca-Cola and IBM received letters and visits from Russian prosecutors warning of potential legal action against the companies and employees last month.

For PR pros who need to explain an unpopular, or at least a controversial, decision, Brendan Griffith, SVP, Reputation Partners, urges emphasizing the “why” behind a choice.

Similarly, Ivan Pollard, center leader, The Conference Board Marketing & Communications Center, says the standard of clear communication is “not just about the what but also about the why and the how.”

In this case, keeping employees and customers safe is a nearly ubiquitous corporate value. Lean on it, is Griffith’s advice. Adds Pollard, "From a communication standpoint, focus on the people, not on the politics. The ethical questions of the human impact must be foremost in your story."

For instance, We’re keeping a presence in Russia out of concern for our Russia-based employees. And, We provide essential food and medical products to Russian citizens, which explains our continued presence.

The reputation cost in such cases, Griffith believes, is minimal. First, people have short memories. While he doesn’t minimize reputation’s importance, Griffith says companies should consider “those people you care about most, your employees and customers,” when making tough decisions. Moreover, “global companies are not going to be able to please everyone,” he adds.

A former CMO of General Mills, Pollard advocates using a “disciplined decision-making process” when considering how core values prompt your company’s stance in a highly charged situation. For instance, consider how communication about Russia today could play after the conflict is over. In addition, how might communication about values and Russia influence your relationships in China, India and elsewhere?

Goldman Sachs

The second issue centers on companies like Goldman Sachs. Famously, the firm trumpeted its departure from Russia on March 10. Goldman, a headline read, was the “first major Wall Street bank to leave after the Ukraine war.” Yet Goldman continues generating revenue by selling Russian debt. As MSNBC anchor Stephanie Ruhle says, Goldman’s exit from Russia is “only partially true.”

Goldman's activity is legal. Several other banks are doing the same thing. A “loophole” in the US sanctions allow such activity, NBC News reports. On the other hand, critics charge Goldman made a lot of noise about leaving Russia.

From a pure PR viewpoint, Goldman’s miscue was communicating its exit so loudly, say Griffith and Amani Wells-Onyioha, operations director of Sole Strategies. Goldman "could have closed its Russia business quietly,” Wells-Onyioha argues.

On the other hand, she says, it's tempting to say look at me. Still, communicating “about everything” is a common mistake. “Unless you have a noble reason to address something, don’t. Be strategic. Not everything is worthy of a comment” or a press release, Wells-Onyioha advises.

She adds quickly, "This is not the same as saying 'no comment.'"

Communicate Strategically

Similarly, Griffith says companies sometimes over-communicate because they are worried about “a backlash should they say nothing.” If we’re not communicating, we must be doing something wrong. Not true, Griffith says.

When faced with a complicated communication choice, such as commenting on remaining in Russia, another consideration is your company’s track record, Griffith advises. “Patagonia is a great company and it’s known for its activism. Is your company?” If not, perhaps staying quiet is a better route.

Not surprisingly, Griffith, Wells-Onyioha and Pollard agree about transparency. “If you communicate, make sure you’re totally clean” and your actions match your words, Wells-Onyioha says. Adds Griffith, “we’d probably not be talking about Goldman if it hadn’t communicated it was leaving Russia.” Says Pollard, “many companies–not just some–talk first and then fail to act later.”