On Aug. 8, The Guardian's Sam Levin shared a review of documents proving that agrochemical company Monsanto launched an elaborate media relations crisis plan to target journalists and activists writing negatively about their products.

"The records reviewed by the Guardian show Monsanto adopted a multi-pronged strategy to target Carey Gillam, a Reuters journalist who investigated the company’s weedkiller and its links to cancer," wrote Levin. "Monsanto, now owned by the German pharmaceutical corporation Bayer, also monitored a not-for-profit food research organization through its 'intelligence fusion center,' a term that the FBI and other law enforcement agencies use for operations focused on surveillance and terrorism."

Disclosed as part of an ongoing court battle over the potential health risks in Monsanto's roundup pesticide, the documents also reveal details of how this "fusion center" operated. For one, it flagged a release of documents that showed the extent of the company's relationship with noted scientists and suggested that negative research about Monsanto's chemicals was intentionally suppressed.

Monsanto also targeted singer/songwriter Neil Young, whose 2015 album "The Monsanto Years" criticized the company's denial of the harmful properties in its chemicals. The company had considered legal action against Young if his messaging around the album's release escalated, Levin reported.

It's Monsanto's targeting of journalist Carey Gillam, however, that grants PR professionals the most revelatory look at just how far the agrochemical giant was willing to go to silence critics.

For communicators, many of the tactics used against Gillam look familiar—a solid SEO strategy, a robust social listening program and relationship-building with editors. In this case, though, they were weaponized in the interest of spinning factual reporting. Here's what we learned.

Work with reporters, not against them

"I knew the company did not like the fact that in my 21 years of reporting on the agrochemical industry—mostly for Reuters—I wrote stories that quoted skeptics as well as fans of Monsanto’s genetically engineered seeds," Gillam wrote in her response to the documents.

"I knew the company didn’t like me reporting about growing unease in the scientific community regarding research that connected Monsanto herbicides to human and environmental health problems. And I knew the company did not welcome the 2017 release of my book, 'Whitewash – The Story of a Weed Killer, Cancer and the Corruption of Science,' which revealed the company’s actions to suppress and manipulate the science surrounding its herbicide business. But I never dreamed I would warrant my own Monsanto action plan."

From the perspective of the person targeted, Monsanto looks like Big Brother. This should remind communicators that when a business makes journalists the enemy, the brand almost always emerges worse for wear.

In an age when the fourth estate is consistently under attack by political talking heads—when reporters are disappeared or murdered for their pursuit of facts—the importance of a profession that traffics in hard, documented information as its only currency should not be understated.

In PR, building relationships is everything. In media relations, doubly so. If Monsanto truly believed that its products and research were on the level, they could have spent the resources used to attack Gillam on educational initiatives, including paid and owned efforts to get out in front of future accusations and, ahem, clear the air regarding misconceptions around its products.

Lessons from a spin-focused crisis plan

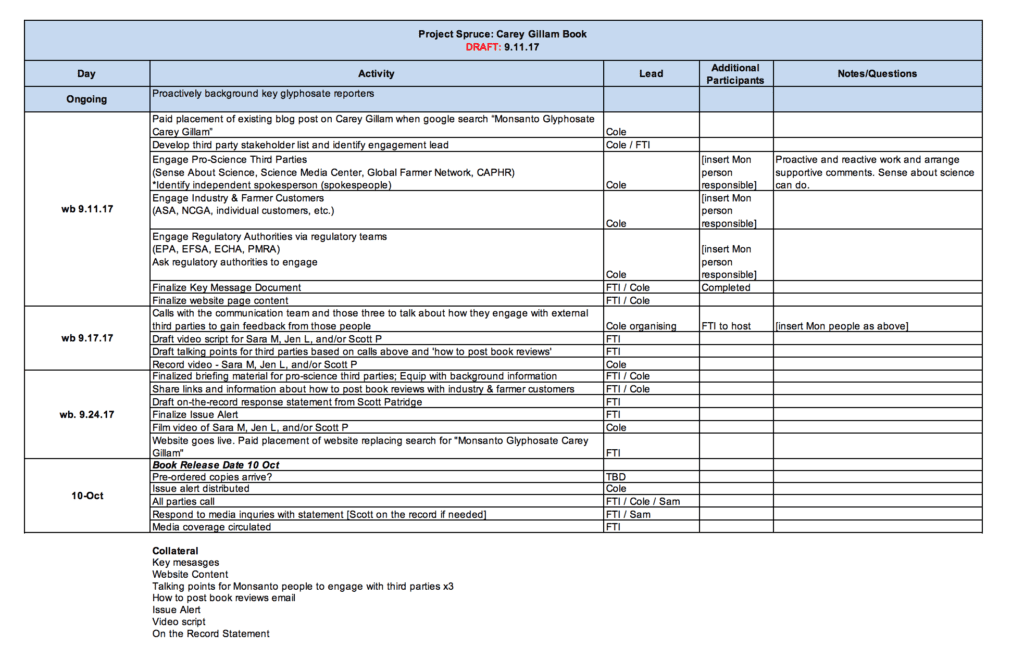

A spreadsheet shared as part of the 50-page document revealed that Monsanto, in partnership with FTI Consulting, shed light on a crisis plan focused solely on targeting Gillam's book launch.

Breaking this down, both best practices and worst practices emerge. First off, the idea of paying for blog posts by third parties in order to downgrade the SEO of Gillam's book is a bad look, but not unheard of. Big brands often spend thousands of dollars in order to rank higher for certain searches. What's most troubling here is that the brand sought to pay for pieces that appeared to look like they were earned and independent—although that's not unheard of, either.

There are some good tactics here: The timed rollout seems particularly thoughtful, as does the observance of both "proactive and reactive work" with pro-science spokespeople to counter claims made in the book. As we'll discuss at our Media Relations Conference in D.C. Dec. 12-13, knowing when and how to activate your influencers or spokespeople can go a long way toward repairing brand reputation.

The questionably unethical tactics, however, say the most about this campaign's intentions. A note to "ask relevant regulatory authorities to engage" reveals the extent to which the brand remains cozy with regulators, suggesting that Monsanto does not operate under transparent oversight. A plan to "show links and information about how to post book reviews with industry & farmer customers" raises ethical considerations around prodding your network of micro-influencers to have your back.

"Shortly after the book’s publication, dozens of 'reviewers' suddenly posted one-star reviews sharing suspiciously similar themes and language," recalled Gillam. "The efforts were not very successful as Amazon removed many reviews it deemed fake or improper."

Treat the editor/reporter relationship as sacred

In her account, Gillam mentioned her one-sided relationship with Monsanto PR while she worked at Reuters.

"The company was perfectly happy with stories that highlighted its new products, or the spread of adoption of its seed technology, or its latest expansion efforts," Gillam writes. "But if a story I wrote quoted a critic of the company or cited scientific research that Monsanto didn’t consider valid, Monsanto would repeatedly complain to editors, tying up editorial time and resources."

She also shared an incriminating email from Monsanto media relations executive Sam Murphey: "We continue to push back on her editors very strongly every chance we get. And we all hope for the day she gets reassigned."

Communicators shouldn't be afraid to push back on reporters if a factual inaccuracy is printed, but to do so around proven facts or research can cross the line into disinformation. Moreover, any PR pro worth their salt understands that the relationship between a reporter and an editor is sacred.

Because most editors uphold their publication's editorial guidelines and standards for sourcing as a badge of honor, attacking those methods by complaining directly to an editor doesn't do anything but harm: it hurts your relationship with the publication, it hurts your brand reputation as proponents of a free press and hurts your network of media partners who truly understand what you do and want to help tell your story.