In a sense, some of the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) communication is as far away from good PR as you can get. As we know, clear, unambiguous, concise communication is the gold standard for PR. Conversely, a joke holds that if the FTC and other government writing were clear, lawyers’ incomes would suffer, since anyone could interpret it.

You want mystery in detective novels and TV thrillers, not business, where uncertainty is like kryptonite.

Yet, based on its communication, about endorsers at least, the FTC spends a lot of time in a cloudy environment. The Commission’s communication isn’t deceptive necessarily, but sometimes even the experts–lawyers who specialize in reading FTC tea leaves–are uncertain about its message and intention.

Indeed, even some of the FTC’s language is dissonant. Nearly everyone uses the terms influencer or creator when speaking about people who tout products on social. Yet the FTC insists on calling them endorsers.

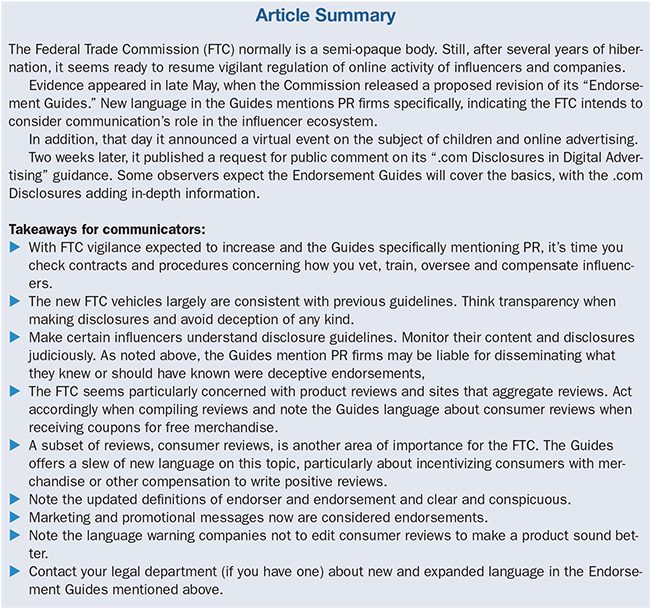

Even when the Sun breaks through the FTC clouds, myriad questions remain. Evidence is May 19, when the FTC released its long-awaited updated Endorsement Guides.

Last revised in 2009–a lifetime ago in internet years–the Guides cover social media compliance. Its aim is protecting consumers from deception and other obfuscation on social.

Communicators may know the Guides for its coverage of disclosures, or how influencers and bloggers must reveal material ties with companies they represent in social posts.

In addition, PR pros may know the Guides for their content that covers what influencers can or cannot say about products they promote on social.

The May 19 release technically is a proposed update of the Endorsement Guides. In fact, this new, 79-page vehicle is a draft and open for public comment.

As such, a final version of the Guides probably won’t publish until 2023 at the earliest, say attorneys Allison Fitzpatrick of Davis & Gilbert and Jim Dudukovich of Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner.

Transparency and Deceptiveness

However, there’s some clear, concise good news for communicators in the Guides. The essence hasn’t changed much since the 2009 update. As Fitzpatrick says, you can reduce the Guides to “transparency and deceptiveness… the FTC is trying to ensure [social media] transparency and stamp out deception.”

So, influencers, creators, endorsers (or whatever you call them) still must transparently disclose they’re creating content or touting a product on behalf of an entity.

As such, you should encounter influencers’ Instagram or TikTok posts clearly displaying hashtags such as: #ad, #paidsponsorhip, #brandpartner, #brandambassador or #IworkforABCbrand. (Don’t search for the word hashtag in the draft Guides; you won’t find it.)

On deceptiveness, endorsers should not make claims about a product they know are untrue or unprovable. Influencers shouldn’t say ‘XYZ pills cure COVID,’ unless they do and your company can prove it.

Particularly germane for PR pros: do not communicate something an influencer says that you know, or should know, is false.

Dudukovich adds a third essence to Fitzpatrick’s transparency and deceptiveness: typicality. In short, don’t represent atypical results as typical in a sponsored social post.

So, perhaps QRS bath salts helped two bald people grow hair last year. Still, 99.9 percent of bald people who used QRS remained hairless. QRS and its influencers should not create social posts touting these atypical cases.

The Specifics

You’re likely thinking this is golden-rule stuff. Even the verbose FTC couldn’t have used 79 pages to explain transparency, deceptiveness and atypicality. True, there’s more.

For instance, the updated Guides touch areas not included in the previous edition. The Guides also emphasize and clarify certain things. Despite this, Dudukovich and Fitzpatrick still have questions about some of the FTC’s intentions. Throughout interviews, both attorneys use phrases like ‘I think we’ll see a, b and c next year from the FTC,’ and ‘I was expecting more specific guidance about x, y and z’ and 'The FTC seems serious about d, e and f.'

Yet there's a method here. Indeed, both lawyers believe the FTC is using the draft Guides as a residence for the basics only. Fitzpatrick thinks the Commission eventually will provide more specific details about influencers, disclosures, etc. via Q&As and staff guidance.

.com Disclosures

However, Dudukovich is convinced an update of the “.com Disclosures: How to Make Effective Disclosures in Digital Advertising” guidance document will contain specifics that the Guides lack. (Sorry, the .com Disclosures is yet another document we’re adding to this complex scenario.) So, while the Guides say you must disclose transparently, the .com Disclosures will show you how a disclosure should look, Dudukovich believes.

He bolsters his theory, noting that on June 3, shortly after the Guides debuted, the FTC “unexpectedly” issued a request for public comment on the .com Disclosures, which were updated last in 2013, when the internet and social media were pups.

Guides' New Content

Returning to the Guides, much of its new content responds to social media trends that have occurred since 2009. For example, the revised Guides offer new content:

- about intermediaries, virtual influencers and disclosures

- that discusses social media marketing aimed at children

- concerning sites that compile reviews and rank products, and

- dealing with consumer reviews

Intermediaries

One of the first specifics that communicators should know about in the revised Guides is language about PR agencies’ liability for FTC violations.

While PR firms previously were advised that they could be held accountable for an influencer’s sins, often they were not. Product manufacturers usually took the hit when an influencer misbehaved.

So, if an influencer touted Company A’s shampoo without disclosing that she was a compensated endorser, Company A paid the fine, not PR pros or marketing agencies.

Ditto if the influencer made a fraudulent claim about the shampoo. Though there were exceptions, PR firms, and even the guilty influencer, usually went unscathed. Again, more often than not, Company A was hit.

However, the new Guides make things clear. “It’s no longer a debate, particularly [if a PR agency or pro] knows, or should have known ,that something was deceptive,” she says. “It's now black and white…if you take part in the deception, you will be held liable.”

For Dudukovich, the FTC’s reasoning is justifiable. It’s essentially granting that the lines between marketing and PR are, indeed, blurred.

Virtual Influencers

The Guides expand the definition of endorsers to include virtual influencers, such as computer-generated avatars and fictional characters. The Guides say an endorser is anything that “appear[s] to be an individual, group, or institution.”

On the other hand, the Guides leave a slew of questions open, Fitzpatrick argues. "I was hoping for more specifics," she says.

For example, do virtual influencers (or the people behind them) need to disclose they’re not real people? And assuming a virtual influencer can’t smell, eat or taste, can one claim, say, Coke tastes better than Pepsi or that a pair of shoes is more comfortable than another? Eventually, the FTC must answer these questions, Fitzpatrick says.

Disclosures

The revised Guides adds language stating that an affiliate marketing relationship requires disclosure. So, for example, a blogger writes about a product, the consumer clicks on a link in the blog and makes a purchase. The blogger receives a fee. A disclosure must inform the consumer of this relationship. Clear.

Yet, as mentioned above, there’s not much instruction about how the FTC wants the disclosure made. That’s troubling since “this is an area rife with abuse and noncompliance,” Dudukovich says.

It’s likely, he adds, at some point the FTC will specify it requires a clear disclosure, not small print at the bottom of the blogger’s bio saying, I receive a portion of sales if you buy something I recommend.

Another example relating to disclosure and touching on transparency and deceptiveness is the Guides’ added language about “clear and conspicuous” disclosure. Such disclosure, the Guides says, is one that “is difficult to miss (i.e., easily noticeable) and easily understandable by ordinary consumers.”

The Guides’ example of a disclosure that doesn’t meet the mark is one easily viewed on a laptop but hard to find on a mobile phone.

It also notes that if a claim about a product or service is aimed at a particular group, let’s say those 65 and older, that group’s viewpoint will constitute “ordinary consumers.”

The Guides also “crack the door open a bit” about when a disclosure is not needed, Dudukovich says. One instance is when nearly everyone in the audience knows that the person posting about a product is a professional influencer and likely receives compensation.

For example, the FTC likely means people such as certain Kardashian family members. Though, again, the Guides is mysterious. There are no names mentioned. So, what the FTC meant here is not 100 percent certain, he says.

Children

The Guides make an interesting point about endorsements directed at children. In short, the FTC says most children lack the knowledge to separate advertising from content, especially in social media. As such, the FTC says it must protect children with particularly clear disclosures.

Again, the Guides’ content whets the appetite for specifics. The Guides’ mention of children, Dudukovich says, is “only a placeholder.” Fortunately, the FTC will hold a virtual event in late October about children and endorsements, including kid influencers. “That should make things clearer,” he adds. In addition, it’s likely the event will add a few months to the timeline before the Guides can debut, again, probably somewhere in 2023.

Review Sites and Consumer Reviews

Even the casual online shopper is aware of reviews, or at least rankings. Nearly every product or service online has stars or numbers or written reviews next to it, ostensibly indicating the product’s quality. Sometimes products have stars, numbers and reviews.

The questions, though, are many.

- Who’s compiling these ratings?

- When you read consumer reviews, are you seeing a cross-section of all opinions or the most favorable ones?

- Are you seeing opinions of consumers who were compensated in any way for their review?

- Are the consumer reviewers also company employees? Family and friends of the company’s owners? Are the consumer reviewers using their real names? Have they submitted multiple reviews under different names?

Based on the Guides’ new content, the FTC is highly concerned about reviews, Fitzpatrick and Dudukovich agree. The FTC seems especially anxious about companies that suppress negative customer reviews, Fitzpatrick adds.

Dudukovich notes FTC angst with companies that cherry-pick good reviews, feature them prominently on sites and stick bad reviews in the equivalent of online Siberia. In addition, the Guides mention prohibitions against editing a submitted review so its words make a product appear better than the reviewer intended.

Fake reviews

Reviews that are fake in any way are of particular concern, Fitzpatrick says, as well as ratings and review sites that allow companies to pay for higher rankings.

Both Dudukovich and Fitzpatrick agree the recent flurry of FTC activity signals the Commission intends "to be a force again" in regulating social media commercial activity, Fitzpatrick says. It was relatively quiet in 2021 and 2020.

As such, it's an excellent time to make certain that your company's vetting, training and oversight of influencers is solid, both attorneys say. Based on the proposed Guides' language, Dudukovich says merely having an influencer sign a form saying she understand FTC disclosure procedure is unlikely to protect a PR firm from exposure.