The New Year’s Eve ball drop in New York is one of the most iconic images of the last hundred years. This year, an estimated one million people will pack Times Square to help ring in 2015 while another billion watch from around the world.

The New Year’s Eve ball drop in New York is one of the most iconic images of the last hundred years. This year, an estimated one million people will pack Times Square to help ring in 2015 while another billion watch from around the world.

In many ways, the tradition is a blending of old and new. Celebrating the New Year is nothing groundbreaking, but this quintessentially New York tradition has an unexpected origin.

The ball drop itself is an artifact from the 19th century. Back then, knowing the precise time was a challenge. Many American cities calculated their own time, meaning the time tended to reflect what city you were in or near, rather than the time zone. Time keeping was of crucial importance to ships at sea. Navigators would use time to calculate their longitudinal coordinates, which meant that a few minutes could be the difference between safe harbor and shipwreck. Captain Robert Wauchope of the British Royal Navy came up with the idea of the the time ball drop. Ports would set up a tall pole with a ball at the top, which would then drop and reach the bottom at noon. This allowed a ship’s navigator to set the time without docking. The method quickly gained popularity, and by the late 1800’s even landlocked cities had them. But the ball didn't drop in Times Square until 1907, two years after the first Times Square New Year’s Eve party.

Traditionally New Yorkers celebrated the New Year on Wall Street, where crowds would gather around Trinity Church to “ring in” the New Year with the church bells. After Adolph Ochs became publisher of The New York Times and moved its headquarters to the intersection of 42nd Street, Broadway and Seventh Avenue, he successfully lobbied the city to rename the area "Times Square." Ochs decided a little more publicity couldn’t hurt. After all, this was a time of gross saturation in the newspaper industry following the advent of Yellow Journalism in the 19th century, and the Times had to do more than stress objectivity to survive.

In a move to show off the lavish new home of his newspaper, Ochs decided to throw a blow-out New Year’s Eve Bash in 1904. He lured the crowds away from Wall Street by promising an all day festival that would end in midnight fireworks. The event was a huge success. Records indicate that more than 200,000 people descended on Times Square that year, and at midnight the crowd could be heard cheering “as far away as Croton-on-Hudson, thirty miles north.”

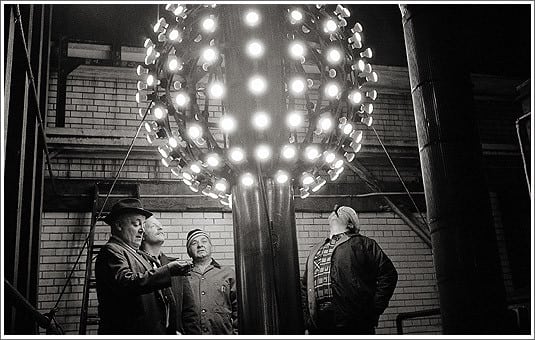

With that, the tradition was born. Two years later, the fireworks display was prohibited by the city, so Ochs borrowed from what was even then outdated technology and promised the lowering of a large, illuminated 700 pound iron and wood ball to signal the end of the year.

Since then, the ball has dropped at midnight in Times Square every year, except in 1942 and 1943 because of wartime light restrictions. And it has proven to be one of the most iconic and long lasting publicity stunts of all time, now serving as a full-blown cultural landmark event.