If PR pros want better results in media relations–getting reporters to respond to our pitches, show up at our press briefings, interview our executives–maybe we should be more like Chick-fil-A.

This idea may chafe some communicators. As part of their philanthropy, the brand’s owners contribute to groups whose policies some see as divisive. Still, Chick-fil-A offers many lessons in relationship building and maintenance, which are the heart of media relations. Allow me to beg your indulgence.

Anyone who’s been to a Chick-fil-A cannot fail to notice one thing, aside from the delicious waffle fries: the consistently and relentlessly cheerful crew. Chick-fil-A employees: 1) make eye contact, 2) smile, 3) speak enthusiastically and 4) don’t just mumble “thank you,” or offer a disinterested grunt after you pay. They say, “My pleasure.” These four behaviors are part of an extensive employee training regime known as Core 4.

Customer Care of Biblical Proportions

In addition, there's a training piece that Chick-fil-A calls “Second-Mile Service.” As you may know, the company is Christian-owned. The training relates a story from the “Gospel of Matthew,” where disciples are urged to walk a second mile. The application for Chick-fil-A employees is they're asked to provide customer service beyond what is expected–and what other fast-food restaurants offer. Hold doors for customers, carry large loads to their cars, bring them free refills.

Does this work?

Data says it does. 2018 marked the third straight year Chick-fil-A topped its customer satisfaction index, according to QSR Magazine, the trade publication of the quick-service industry.

Another report in QSR Magazine showed Chick-fil-A franchises earn more per restaurant than McDonalds, Starbucks and Subway combined.

Chick-fil-A has the strongest fast-food brand personality, ranking highest in three of five brand personality dimensions (sincerity, excitement and competence), according to a Zion & Zion study released May 29, 2019. It ranked second in a fourth personality dimension (sophistication). The study looked at the 26 largest fast-food brands, surveying 4,400 adults and using results from 3,200 who were familiar with the restaurants they were asked about.

This favorable personality creates a secondary effect: Customers are not only happier, they are nicer in response. Just stand in a Chick-fil-A line and watch customers interact with employees. Compare that to what you see at the cash register line of other fast-food restaurants. It’s harder to be mean to nice people.

Media Relations as Fast-Food Service

The parallel for PR pros is clear: We are, especially when executing media relations duties, service personnel. Our job is to serve brands and their employees with media attention and, where possible, positive coverage.

We can only be successful in these interactions–over the long-term–by treating journalists with respect and politeness.

To be sure, PR has its adversarial moments; this can be a bare-knuckles business. We must aggressively push back against inaccurate or unfair reporting. Similarly, we must argue to correct biased TV news chyrons on the fly.

But even these prickly situations, if handled with grace, facts and respect for the journalist, can yield better results than screaming on the phone and sending ALL CAPS emails.

Application to Media Relations

So, how do we apply Chick-fil-A’s lessons to media relations? Is it just about adding smiling emojis to our email pitches? No. Remember that at its base, Core 4 is not about smiles or cheerfulness, it’s about respect and relationships.

At the heart of that is understanding what a journalist’s job is–their daily workflow, demands on their time, what they and their organization consider newsworthy and when not to bother them. Yes, unless you’re offering the story of the century, it’s likely you’re bothering them.

Every fast-food restaurant is competing for your business. Similarly, each day there are 100 other PR pros competing for the attention of the one reporter you’re targeting.

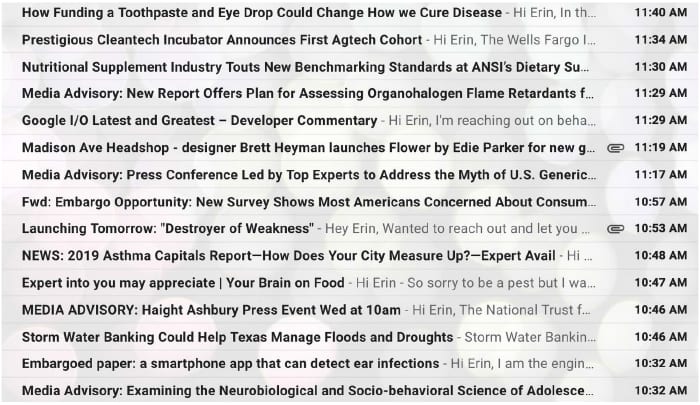

Business Insider reporter Erin Brodwin tweeted a screen shot of her email inbox. As you see (below), it shows 15 unsolicited pitches in about 60 minutes.

Aside from the volume, take a close look at the pitches. Brodwin is a health and tech reporter. Why is she getting a pitch about weather (third email from the bottom)? Her bio says she “writes about the latest developments in the world of drugs, neuroscience, food, and nutrition.” So is she going to write about your head shop (sixth email from the top)? Your nutritional supplement? And just count how many instances of “reaching out” you see in these 15 pitches.

We can do better.

A Media Relations Checklist

Here, then, are some guidelines. They are are fundamental, but bear more than repeating. Institutionalize them the way Chick-fil-A has institutionalized its training methods:

- Help educate your company’s executives on story criteria. To a journalist, a story must be true, timely, newsworthy, substantial, have impact and be relevant to her readers. Not everything your company does or says is newsworthy just because your company thinks so. Less is more. Work with your brand to create fewer–but more newsworthy–statements, events and opportunities.

- Research the journalists you’re pitching. I know many PR pros–especially younger ones at big shops–are required to show that they’ve made a certain number of pitches per issue. This makes it tough. But you’ll get much better results for your company by pitching the right journalist rather than a lot of journalists.

- Get the name of the reporter right. Don’t send “Dear REPORTER NAME HERE” emails. Don’t assume gender based on name.

- Avoid Stretching. Don’t try lame ways to connect your pitch to a reporter’s beat when there’s no connection.

- Don’t be glib; be a grown-up. On your first email contact with a journalist you don’t know, address her by an honorific and her last name. If she responds, and signs her email with her first name, then you have permission to use her first name. Few things chafe a journalist–or, frankly, anybody–more than unearned familiarity.

- Don’t try to snow anyone. Open your pitch by clearly identifying who you are and where you work.

- Don’t use profanity or crude language in your pitch. You’re only humiliating yourself. And use correct punctuation. See: grown-up.

- Don’t “reach out,” “check in,” “circle back,” “touch base with” or use other euphemisms to try to minimize your impact on the journalist’s life. You know you’re imposing. They know you’re imposing. Do it quickly and professionally and say plainly and politely what you want.

- Offer something of value. If you have a newsworthy story, interview, statement or so on, the reporter will be grateful. In addition, you’ve started building a relationship. The journalist likely will take your email or call again.

- Avoid shaming. Want to see a list of worst practices? Look at journalists’ Twitter feeds, where PR practitioners are routinely flack-shamed. For instance, witness these piteous “gas lighting” tricks, as described by Vox internet culture reporter Aja Romano.

Like Chick-fil-A, go the second mile where appropriate. An example: I emailed reporters at a Washington news bureau and received no response. Since I am acquainted with them this surprised me. I sent a polite follow-up and again received no reply.

Moments later, I realized, via photos on Twitter, that all the reporters in the bureau were at a memorial service for a former colleague.

I felt terrible. I sent the journalists one more email, apologizing for intruding on their grief. One responded politely and gratefully. That’s not a tactic. That’s a relationship.

NOTE: This content appeared originally in PRNEWS, May, 2019. For subscription information, please visit: https://www.prnewsonline.com/subscribe-now/

Frank Ahrens is VP at BGR Public Relations. He is a former VP, global corporate communications, at Hyundai Motor, and was a Washington Post journalist.