In any compelling story there has to be a hero and a villain—and today’s corporate crises are fitting right into that narrative. If a crisis doesn’t have an easily definable villain—Travis Kalanick at Uber, Elizabeth Holmes at Theranos or a hero like Market Basket’s Arthur Demoulas—they’d be out of the news cycle in minutes, not having movies made and books written about them. Whether we like it or not, the media and ultimately the public will declare heroes and villains.

Take two recent brand crises, the cancelation of the reboot of Roseanne Barr’s TV series on ABC and mounting lawsuits against Purdue Pharma for its role in the opioid crisis. Barr is an obvious villain, since her Twitter habits may have flown under the radar for many of us, but were not a secret to her employer. But in all the brouhaha, a surprise hero emerged: Sanofi, manufacturer of Ambien, which rebuffed Barr’s excuse that her statements were the result of “Ambien tweeting.”

In contrast, when concerns about opioid addition began to surface in voter surveys back in 2015, there was no obvious villain. The epidemic was attributed to a host of causes: doctors over-prescribing, loss of middle-class jobs, bad medical care, NAFTA, lack of adequate mental health workers—so many villains no one knew quite where to point their collective finger. And then along came revelations about the perfidies of the privately held pharmaceutical giant Purdue Pharma.

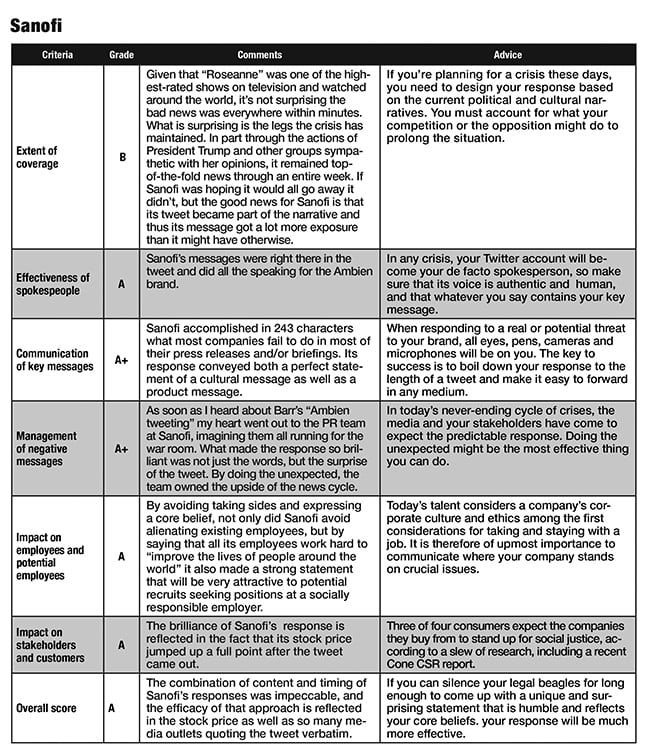

Sanofi

First let’s examine the crisis management involved in the firing of Roseanne Barr, and her attempt to attribute blame for her racist tweet on the sleep medication Ambien. On a Tuesday night in late May, she tweeted a series of derogatory comments that reflected racism and bizarre conspiracy theories relative to Chelsea Clinton. Within hours hours several members of her staff had quit, Twitter was raging with horrified reactions and advertisers were getting nervous.

By 11 am Pacific Time, fewer than 8 hours after the original tweet appeared, ABC Entertainment president Channing Dungey announced the cancellation of Barr’s series. Channing’s statement was followed by a personal tweet from Bob Iger, the CEO of Disney, retweeting Dungey’s announcement and adding his comment: “There was only one thing to do here, and that was the right thing.”

In her initial explanation Barr said she was “Ambien tweeting,” blaming her stream of 240-character slurs on a lack of sleep and the sleeping aid Ambien.

Despite her apologies and explanations, the nature of her tweets made it easy for her to fit right into the role of villain. And her bosses came out as heroes for quickly taking action to cancel the show, despite its huge ratings and solid adverting base.

But it was Sanofi, manufacturers of Ambien, that really came out on top, taking a giant leap forward for the world of crisis communications with its response within hours of Barr’s blaming her tweetstorm on Ambien.

Trigger alert to corporate lawyers—you may want to stop reading now.

What a Tweet

Typical pharma (and frankly most corporate communications departments) would have chosen to lie low and hope to avoid fallout from the kerfuffle. At best most might have tried to distance themselves by saying one shouldn’t be tweeting while taking Ambien. Instead Sanofi issued one of the wittiest 280-character comebacks in corporate communications history: “People of all races, religions and nationalities work at Sanofi every day to improve the lives of people around the world. While all pharmaceutical treatments have side effects, racism is not a known side effect of any Sanofi medication.”

Instantly the crisis had a hero, and when the incident is cited in text books and corporate communication classes for years to come, Sanofi and Disney’s Iger will be used as examples of the best in crisis management.

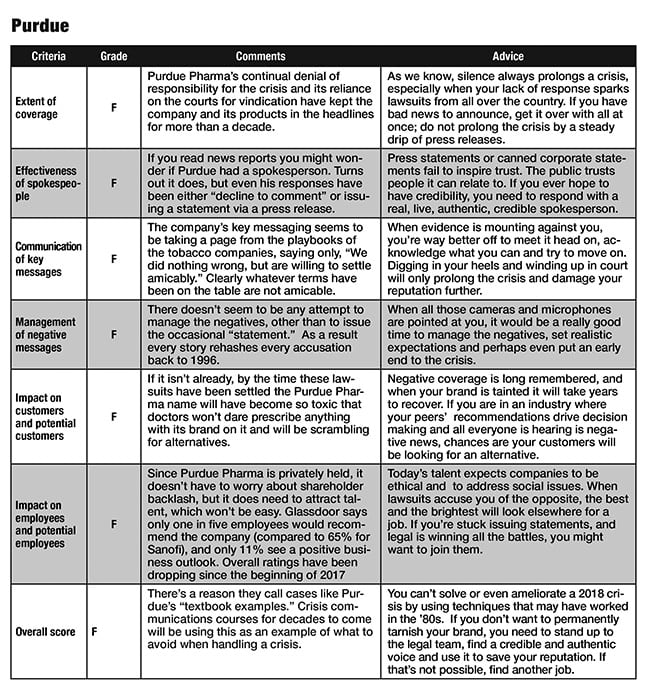

Purdue Pharma

In contrast, Purdue Pharma will follow tobacco companies, Wells Fargo, Volkswagen and BP into the textbooks for how not to manage a crisis. What these brands share is a toxic corporate culture making them inevitable villains in the face of crisis.

Purdue’s problems began more than a decade ago, when it was charged with and eventually pled guilty to a felony charge for “misbranding” (i.e. downplaying the addiction risk of) OxyContin, despite the fact there was no scientific evidence to back up the claim it was “less addictive.”

Meanwhile in 2006, investigators from the Justice Department and reporters kept running into data showing Purdue knew when it launched Oxy that the drug had uniquely addictive properties, but it failed to properly disclosed any issues. According to news reports, Purdue also was aware it was frequently being crushed and snorted as a way to get high as early as 1996. That hadn’t stopped it from continuing to wage an aggressive promotion campaign for the drug as “less prone to abuse and addiction than other painkillers.” For reasons that remain murky, the Bush Justice Department settled the case against Purdue in 2007.

More recent investigations revealed an inordinate amount of the drug was ending up in small rural counties. News reports surfaced that in 10 years, drug companies shipped nearly 21 million opioid painkillers to one rural county in West Virginia, population 2,900—more than 7,200 pills for every person there. These news reports prompted congressional investigations that are ongoing, but fraught with the usual political logjams.

In the meantime, states and counties lost patience. With human and financial costs mounting, states as well as individual counties and municipalities are following the script of the lawyers who took on big tobacco in the ’90s. As of this writing states and municipalities have filed more than 100 lawsuits against Purdue and other pharmaceutical manufacturers, with more suits coming every week.

Purdue’s standard response is the crisis communications version of a very dry martini: 9 parts vigorous denial, 2 parts “we will fight this in court,” topped with a tiny garnish of “we regret the crisis.” It created a “Get the Facts” web page in response to the crisis in 2016 but the last time it was updated was more than one year ago. Just this past February, Purdue announced it would no longer “promote opioids to prescribers” and referred all questions about opioid products to the medical affairs department (i.e. lawyers.), but the link to that website has expired. As a result Purdue Pharma and its executives collectively have donned Darth Vader masks. The public has found its villain.

CONTACT: [email protected]